A popular story from the Mahabharata is that of Yudhisthira and his dog. In the 16th book of this epic, the Pandavas, having renounced their kingdom begin their final journey towards the Himalayas. The arduous climb takes a toll, and one by one family members are lost. In the end, only Yudishtira and his canine friend, who has been with him since the start of this journey, make it to the top. They are welcomed by Lord Indra, who invites Yudhishthira to an onward journey to heaven, provided he leaves the dog behind. Yudhishthira refuses firmly, even if it means perishing on earth. It is then revealed that this was his final test, and the dog is, in fact, the God of Dharma, who blesses Yudhishthira for his righteousness.

Animals have always found their way into our stories, harbouring the missing pieces in our narrative, either as depictions of what the world needs or reminders of what the world is. Before we learn anything about crows, we learn that they are resourceful. Before we learn anything about foxes, we learn that they are cunning. In anthropomorphising animals in our stories, we find ways to differentiate the right from the wrong and highlight the subtle rules our world lives by. But who says these stories have to stop at childhood?

Animalia Indica: The Finest Animal Stories In Indian Literature brings some of the greatest storytellers and their animal-based narratives under one roof. Edited by Sumana Roy, Animalia Indica carries names such as Rudyard Kipling, Ruskin Bond, RK Narayan and Vikram Seth, to name a few. Yudhistira’s dog may have had an ulterior motive, but the animals of the Animalia Indica kingdom are mostly animals, not virtues or deities in disguise or as Roy puts it in the introduction “stand-ins” for humans.

The stories (and a poem by Vikram Seth that rehashes the Crocodile and Monkey story), which are written in English and translated from regional languages, are as varied as the animal kingdom itself. Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Mahesh tugs at your heart as it wraps farmer distress and religionism in a tender human-animal relationship. In Manjula Padmanabhan’s The Copper-tailed Skink, an American Biologist examines her struggles with starting a family against the backdrop of a populated India and the discovery of a Copper-tailed skink, but only the female species. George Orwell’s Shooting an Elephant is a sort of reverse take on imperialism, as a colonial policeman in Burma has to shoot the elephant. Not because he wants to, but because he probably has to. “And it was at this moment, as I stood there with the rifle in my hands, that I first grasped the hollowness, the futility of the white man’s dominion in the East,” writes Orwell. In Snake, Sujatha (S Rangarajan) throws a motley of characters amidst a snake, and the result is both hilarious and entertaining. Sadly, not for the snake in this story.

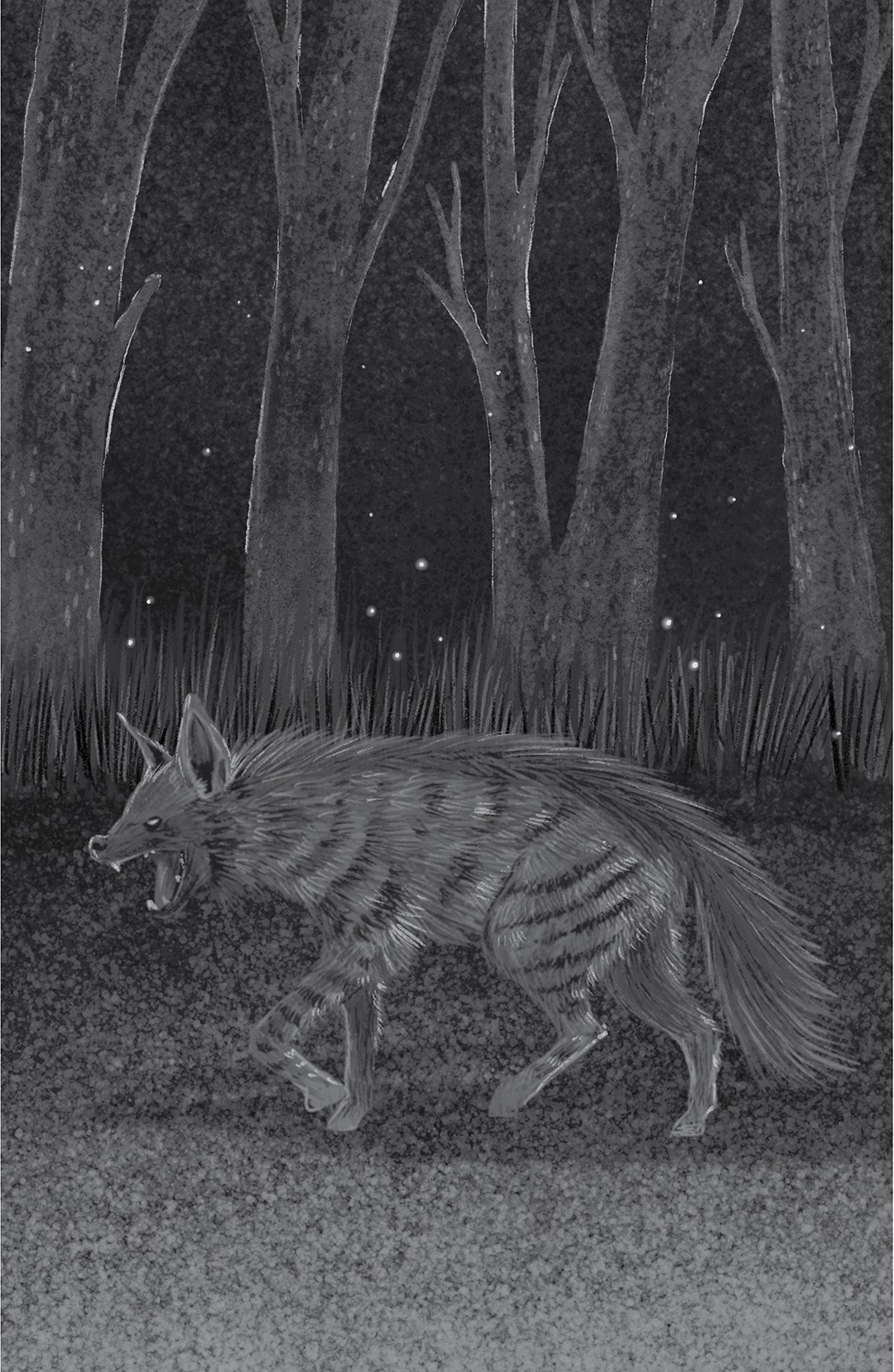

The evocative illustrations by Rohan Dahotre are an essential part of Animalia Indica. Whether it is the elephant with a forlorn look before Orwell’s story or the tiger with its piercing eyes before The Last Tiger, these illustrations seem to remind us that we maybe reading fiction, but they could very well be accounts of real animals.

In the preface of Perumal Murugan’s novel Poonachi, the author writes, “I am fearful of writing about humans; even more fearful of writing about gods.” An excerpt from Poonachi makes an appearance in Animalia Indica in which we find an old couple inviting a goat kid into their otherwise dull life. “Goats are problem-free, harmless and above all, energetic,” wrote Murugan in the same preface. When you finish reading all the stories in Animalia Indica you find yourself inadvertently nodding to Murugan’s sentiments. As agents of sagacity and mirrors of human emotions, the animals in these stories aid to articulate the world around them. Even when they are just being animals, as in the case of Ruskin Bond’s The Last Tiger, we find lines like these – “The deer’s life is over, but he has not lived in fear of death. It is only man’s imagination and fear of the hereafter that makes him afraid of meeting death. In the jungle, sudden death appears at intervals.” In the presence of such eminent writers, the stories in Animalia Indica are both reflective of the world around us, and the world within us.

Between its pages, Animalia Indica spans a century of animal-based stories and storytelling. As you navigate your way through the book, you sense the changing landscape and the changing times. Yes, a lot has changed, but in the end, what stays with you is the question – has it really?

'Animalia Indica: The Finest Animal Stories In Indian Literature' published by Aleph Book Company is edited by Sumana Roy with illustrations by Rohan Dahotre . You can buy it online.