I encountered my first Whale Shark on one of my offshore surveys at Rushikulya, Odisha in May 2010. I was there to monitor the breeding aggregation of Olive Ridley Sea Turtles. I spotted the juvenile 14-footer cruising with ease, moving along with my boat. It was a spectacular sight. As a marine biologist, I always wanted to work on marine fauna, but sea turtles had thus far held my interest. I never imagined that I would also join the handful of people working on Whale Shark conservation in India.

Whale or Shark?

Interestingly, the Whale Shark is the largest fish on earth. It is not a mammal, so the Whale Shark is in fact a shark and not a whale. It can weigh as much as 21 metric tons and grow to a length of approximately 14m (that’s a little longer than a Volvo bus). Although distributed widely across tropical and warm temperate seas, we have limited information on the population trends of this species, especially along the Indian coastline. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Whale Sharks are listed as endangered.

Whale Sharks are solitary animals – they don’t move around in groups. Every year, they are seen aggregating in the waters of Gujarat, though no one really knows why they migrate here. From September to March, they are present along the Saurashtra coast where, due to a lack of legal protection, they were once brutally hunted and slaughtered on an extensive scale, until 2001.

"Shores of Silence"

The plight of Whale Sharks in Gujarat was brought into the limelight by renowned filmmaker Mike Pandey in 2000. His movie “Shores of Silence” was an insight into the grim reality faced by Whale Sharks in Gujarat; it won him a ‘Green Oscar’. The movie was instrumental in bringing about major policy changes in India. As a result of the film and intensive lobbying by Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), in 2001 the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) listed the Whale Shark on Schedule I of the Indian Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972, according the species the same level of protection as tigers and rhinos. It was the first fish in India to get protected status.

In 2003, lobbying efforts by India and the Philippines to gain protection for the species among international groups paid off, and the fish was included under Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), banning it from international trade.

Yet protection on paper hasn’t been enough to save the species. Unregulated and unsustainable fishing practices to meet international trade demand for shark fins, liver oil, skin and meat; accidental entanglement in fishing nets; collisions with boats; and extensive coastal pollution continue to be major threats to the survival of this species.

WTI conducted a survey in 2004 along coastal villages and communities in Saurashtra, in an attempt to understand awareness levels among the local fishers on poaching and the legal status of Whale Sharks. The result was not very surprising: the awareness level was as low as 19 per cent in Veraval, the hub of Whale Shark fisheries in the region.

Soon after, the WTI launched a campaign to save the Whale Shark, with the support of Tata Chemicals Limited (TCL) and the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW). The aim was to build awareness about the species’ protected status and urge the local fishing community to stop the illegal killings and become the fish’s protectors.

The ‘Save the Whale Shark’ campaign, which ran for four years (from 2004-2008), used many methods to reach out to the public. A life-sized inflatable Whale Shark model turned out to be the star attraction of the campaign and was much in demand at all campaign locations. Religious leader Shri Morari Bapu, who was famous for his kathas (discourses), became involved. He urged the fisher community not to kill the Whale Shark, equating it to a beloved daughter returning to her parental home for childbirth. He touched the hearts of the fisher community, providing a compelling reason for them to stop killing Whale Sharks.

This story, however, remained a story until 2013, when the first whale shark pup was recorded off the Saurashtra coast. As it turned out, Morari Bapu was right. Whale Sharks do indeed breed in Gujarat waters, though no one ever had any information about this before. Since then, six more Whale Shark pups, also known as juveniles have been recorded from the Saurashtra coast.

Shores of Saviours

As a result of the campaign, the targeted killing of Whale Sharks stopped on the Saurashtra coast, although several small events throughout the year – such as celebrating International Whale Shark Day and Gujarat Whale Shark Day – continue. Fishers who once killed these fish became their proud protectors. They also started to release any Whale Sharks that became accidentally entangled in their nets. WTI intervened here as well, and compensation for the loss of fishing nets damaged during Whale Shark rescues was approved by the Department of Forests, Government of Gujarat. Between 2005 and 2015, the Gujarat Forest Department gave more than USD 10,500 to fishers who voluntarily cut their nets to release accidentally entangled Whale Sharks. From 2005 till April 2017, 672 Whale Sharks had been voluntarily released by the fishers along the coast.

I joined WTI in 2014. After working on the sea turtles of Orissa and communities of coastal Karnataka, I had to manage the Coral Reef Recovery Project and the Whale Shark Conservation Project, both in Gujarat. However, I was keener to understand the cryptic Whale Sharks than the corals. It wasn’t just me; everyone wanted to know more about Whale Sharks.

Conservation Science

Today, Gujarat has become a haven for Whale Sharks. WTI turned to investigate the mystery behind this fish. Where is it coming from? Where does it go? Why does it aggregate around the Saurashtra coast? Are there any other aggregating sites along the Indian coast? Are the Whale Sharks coming to Indian waters genetically unique?

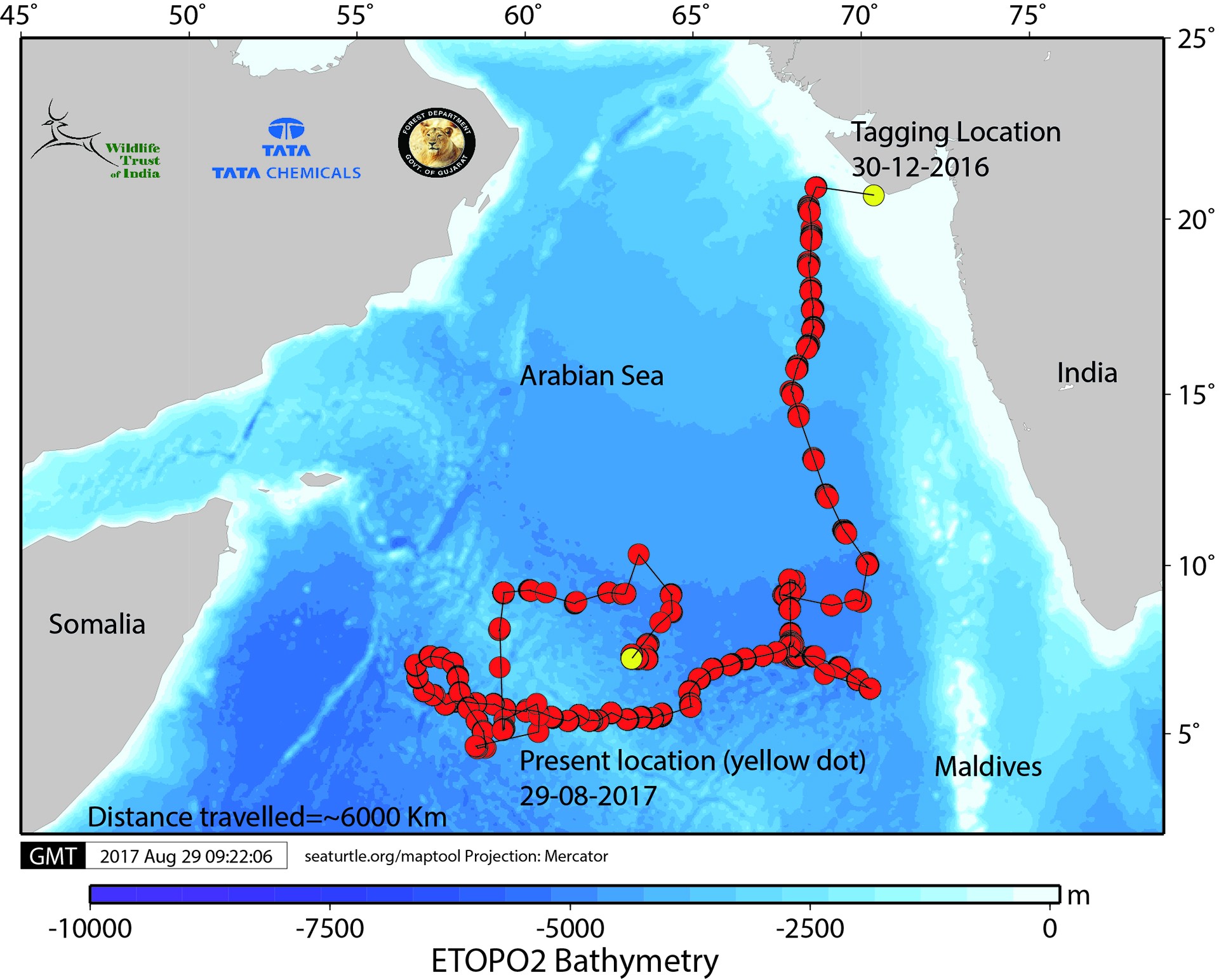

With these questions in mind, the third phase of the project started in 2011; the fourth phase in 2014. The major objective was to crack the migratory route of Whale Sharks. For this, the project initiated the first-ever satellite tracking of Whale Sharks. The project team tagged six Whale Sharks between 2011 and 2016. However, due to multiple reasons – either technical errors or physical damage – the tracking duration ranged between 1-45 days. No one ever imagined that the seventh satellite tagging, on 30 December last year, 2016, would create history in Whale Shark tracking studies, as the female, tagged near Sutrapada fishing village, became the longest-tracked Whale Shark (222 days as on 29 August and counting) from the Indian subcontinent. This was a stupendous feat for Whale Sharks conservation research and for the project.

A survey conducted by WTI with the support of the IUCN and the East Godavari River Estuarine Ecosystem (EGREE) Foundation to document other Whale Shark aggregation sites revealed that six other Whale Shark aggregating sites exist outside Gujarat. The habitat preference study conducted by Indian Institutes of Science Education and Research (IISER) in Kolkata and the Whale Shark molecular studies outsourced to the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) in Dehradun are yet to report their findings. With these results, we will understand more about which habitats these Whale Sharks prefer, and whether these populations are genetically different from Whale Shark populations in other parts of the world.

A Happy Ending?

The Whale Shark Conservation Project is the most successful conservation action project undertaken in the history of WTI. Seven towns including Ahmedabad, Porbandar and Diu have adopted the Whale Shark as their mascot. This participatory project has won several conservation laurels, including the Green Governance Award for Tata Chemicals Ltd. in 2005 and the UNDP-MoEF Indian Biodiversity Award for the Junagadh Forest Division in 2014. The project also won international acclaim at the Whale Shark Conservation Conference at Doha, Qatar in May last year, where experts noted that the approach deployed by WTI and TCL serves as a role model for other developing nations where traditional values are strong.

The Gujarat waters might be safe for Whale Sharks, but things are not as happy as they look. Other coastal states are not as friendly towards Whale Sharks as Gujarat. Unfortunately, landings of accidentally entangled Whale Sharks are still practised. Just this month, WTI initiated a Whale Shark project in Kerala and Lakshadweep, to expand the reach of the awareness campaign.

The good news is that citizens are becoming more aware of Whale Sharks. Fishers know that responsible watchdogs – like the WTI but also like-minded NGOs and concerned individuals – will interfere when they try to land a Whale Shark or any other protected species. Social media is also very vigilant and news of slaughter or illegal trade makes it online the very same day. Now, Whale Shark conservation rests not only with scientists. Recreational scuba divers, fishers, researchers, tourists, and crew members all contribute. Indeed, more community participation is key to the sustained success of Whale Shark conservation.

Notes from the field by Charan Kumar Paidi, a WTI field officer

"Barrel ni halat kevi chhe?" (How is the condition of the Whale Shark?)

"Tofan kare chhe ke nai? Active chhe? Jivti chhe?” (Is it breathing, active? Is it alive?)

"Ketle dur chho?" (How much farther from the shore?)

Early in the morning of December 30 last year, I heard my colleague Farukhkha Bloch speaking loudly on his mobile phone, trying to get as much information from the fisherfolk on the other end of the line. We were at our base camp at Veraval. We got the call from Sutrapada, which is around 23km away. He told the person, “Give us 30 minutes, we will reach there soon.” Then he turned to me and said: “We have a Whale Shark to attend to.” Farukhkha was on a calling spree, contacting forest department officers and fishers to arrange boats.

Organising a rescue trip is no easy task. Prakash, our veteran field assistant, started packing the rescue bag. I took out the checklist and handed it over to him. Everything had to be there – wet suits, snorkels, flippers, satellite tags, tag-fixing tools, a first aid kit, life jackets, GPS, etc – because once we hit the sea there was no way we could return. I took out the satellite transmitter and checked its status. If the Whale Shark was in good condition we would tag her with it. Farukhkha came to our base camp and told me that the cab would be there in 5 minutes, so we had to be quick.

We reached Sutrapada fishing village half an hour later. Based on the telephone conversation, we knew the location we had to get to was nearly 20 minutes away from the shore. We boarded the boat. Farukhkha nodded. The captain put the boat into full throttle.

I got on board and started to activate the satellite transmitter. After 20 minutes of travel and around 10 minutes of searching, we got to where we needed to be and located the boat from which Farukhkha got the call. The situation was a little different to what I had imagined. I had no idea that restraining a Whale Shark was so strenuous. I saw four people holding the net on the starboard side, where it was trapped. The captain of the boat was orienting the boat on its side so that the fish didn’t drift toward the engine.

When a Whale Shark is entangled, fishers will stop moving the boat further, so as to save it. But once the boat is stopped it starts to drift, and there is a chance the shark may get entangled in the propeller or rudder below (even though the propeller is not running. So the captain of the boat will always orient the boat keeping the Whale Shark in the net to one side.

I saw the female, around 21 feet long, completely wrapped up in the fishing nets. We approached from the port side, and then Prakash and I took a leap and landed on the boat. We started to pull at the net. After a long, tiring effort, we could see the dorsal fin of the Whale Shark, where Whale Sharks are usually tagged.

The fishers were still struggling to keep the animal calm, while Prakash and I started our tagging operation. With a hand-held drill, we made a small hole at the base of its first dorsal fin, so that we could mount the satellite transmitter. (There are many methods of tagging, but the drill and bolt method is the most efficient.) The tagging was a success. Then came the critical part of cutting the net and releasing the Whale Shark, making sure not to get the tag entangled in the fishing net in the process.

"Jadap thi jal kapi nakh and dhyan purvak tag lagavi de jadapthi...!" (Cut the net fast and keep an eye on the tag to make sure it is fixed properly…and be careful) Those were Farukhkha’s instructions.

"Ane jem bane em jaldi thi chhodi de...! " (Release it fast don’t be late..!)

Mesh by mesh, we cut the net and released the whale shark.

The satellite tag on her back, “Cerulean” (that’s what I like to call her) dived into the deep blue sea. At the time, no one ever imagined that she would be the longest-tracked Whale Shark from the Indian subcontinent. With joy in our hearts, we returned to the shore.

The next day, back at base camp, I eagerly logged on to ARGOS (our satellite data download site) to check the transmitter status. Yes! We had a signal. She was heading west.

Charan Kumar Paidi is a marine biologist who completed his Masters in Marine Biology from Pondicherry Central University. He is part of WTI’s Whale Shark Conservation Project and works under Sajan John.