Two years ago, in 2015, just like my friend Shreya Yadav wrote in this story, I spent more time finning in the waters of the Lakshadweep atolls than walking on land. While she was trying to understand coral reef recovery by counting coral recruits, or babies, I was busy counting the number and kinds of herbivorous fish found in the reefs, and also analysing how much they ate.

What herbivorous fish eat is of prime importance in reef recovery. They graze on algae and they graze non-stop. They do this all the time, but their work comes into focus most during coral bleaching events, when the balance between coral and algae has shifted. When the reefs have more dead coral than live, algae can quickly take over and dominate the benthic composition. But thanks to the grazing functions of reef herbivores, which are some of the most amazing and beautiful creatures I have seen, the reef can be cleared of algae, making way for baby corals, or new coral recruits to settle, grow and become part of one of the planet’s richest ecosystems. In the absence of herbivorous fish, the algae can smother coral and jeopardise reef ecosystems. Here’s how. (In India, fishing of reef herbivores happens at a very small scale. In fact, Lakshadweep has healthy herbivorous fish populations. In other parts of the world, however, like the Caribbean, these fishes are heavily fished, which has an impact on coral reef recovery in those regions.)

Through this story, I get to share fascinating insights on these fishes and tell you what a big lesson I learned from them.

So, to begin, these herbivorous fishes are one of four types: Grazers, Scrapers, Excavators and Browsers. They are grouped differently because they differ in the way they eat algae. For example, grazers simply crop the algae without uprooting it from the reef, whereas scrapers and excavators don’t just eat the algae, they also scrape the underlying calcium carbonate reef structure.

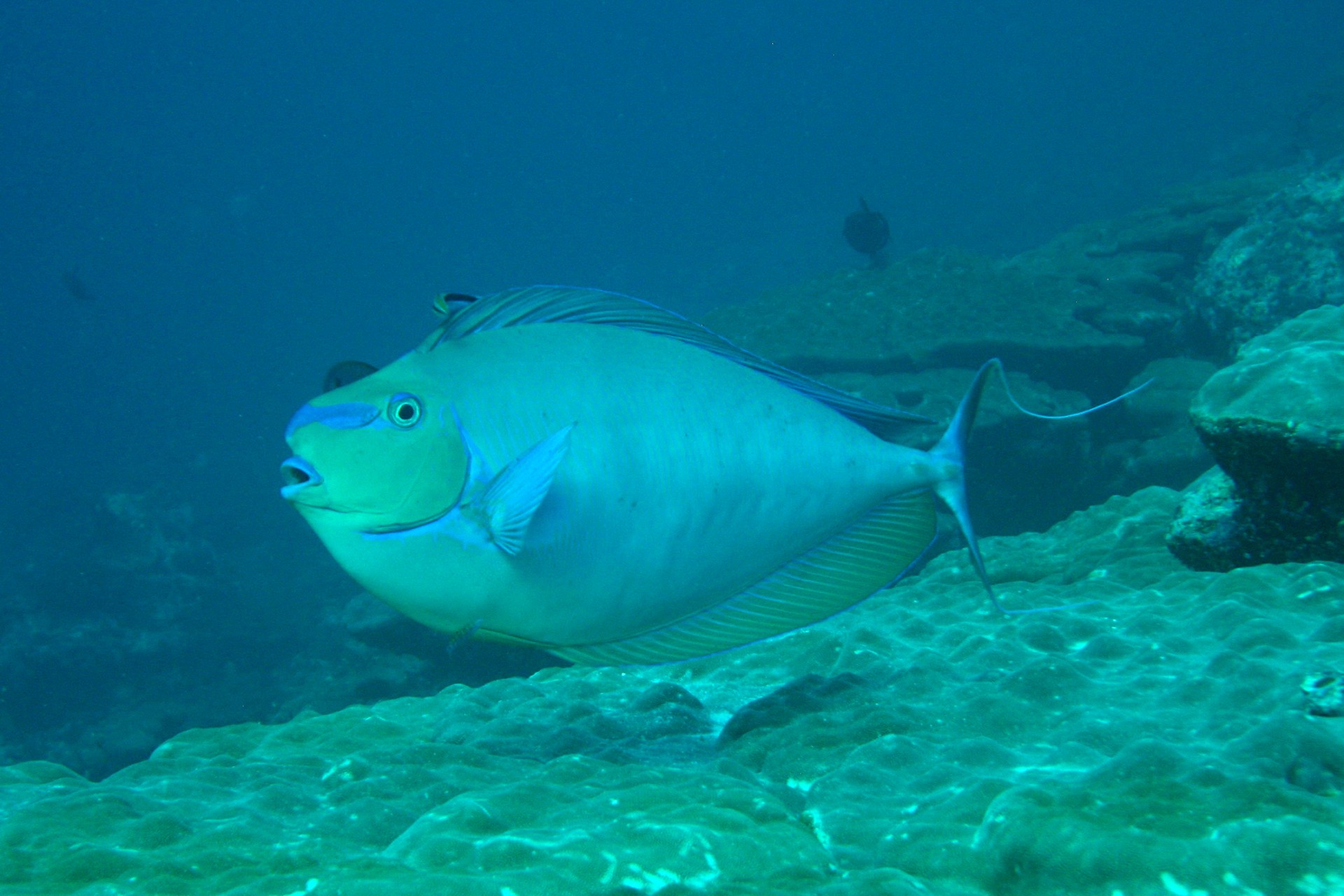

My initial dives were to familiarise myself with my study species, which included surgeonfish, unicornfish, rabbitfish and parrotfish. The stuff of dreamlands – exactly as their names suggest. I would watch them as they munched on the algae, and make notes. If I was quick enough, I would draw them while underwater, or get a picture. Of all these, the parrotfishes were the most beautiful – just look at their delightfully garish fashion sense.

Only later did I realise what I had got myself into!

It turns out that parrotfish are a classification nightmare. They change their colours and patterns as they grow from babies to adolescents to adults. And the change is dramatic. This required me to memorise 20 species, with three variations each. That’s not all! Many of them also show sexual dimorphism just as birds do – that is, males and females look different.

For my study, I had to know who was eating how much algae. For this, I put out a bunch of GoPros on the reef to film how much algae each herbivorous fish eats (i.e. count the number of bites each individual takes in an hour). I had about 20 hours of underwater footage to go through after that.

Parrotfish spend up to 90 percent of their day foraging. Small parrotfish are classified as scrapers; large ones are excavators. Their beaks are used to scrape algae and the soft part of coral from coral reefs, and are strong enough to leave noticeable scars in the coral. The fish grind their food and bits of coral along with it, with plate-like teeth in their throats.

While analysing, I saw that some fish took 5 bites and swam away while others stayed longer to take anything from 50 to 150 bites. If only I knew what a mammoth task I had set myself up for. Initially, it was exciting to see and hear so many of them in my videos, but when it came to counting every single bite each one took, well….

After all that eating, get this: They poop fine white sand (yes, literally) – and lots of it! That’s because they end up scraping a bit of the reef along with the algae. So they eat the algae and poop the calcium carbonate, which is the white sand we see on beaches. Each one can produce up to 320 kilograms of sand every year, as this humorous video explains. Just picture this! I have felt it on my face and in my scuba suit several times.

Another thing that parrotfish sometimes do is form mixed-species feeding shoals (of around 3 to 5 species, usually including the Greenthroat Parrotfish, Striated Surgeonfish, Striped Unicornfish, and the Powder-blue Tang). Shoaling with similar-coloured and similar-sized species is basically anti-predatory behaviour, to reduce their risk of getting eaten. They travel in large numbers raiding the reefs and leaving behind white clouds of calcium carbonate along their trail. Too bad if you are halfway through on your data-collection transect doing your fish counts, or they happen to travel in the path where you left your Go Pro to film fish bites. Many times, I have had to abandon my transect and start all over again after a few minutes of them leaving. Very often, many other individuals from the reef join these shoals as they pass by. What can insignificant mortals do in that case? Well, not much. Call it a dive and come back the next day to repeat the transect, all the while praying that they are empathetic to my cause.

Now, let’s talk about sex. Parrotfish can change their sex repeatedly throughout their lives. They are proof that heterosexual monogamy is not nature’s rule. Parrotfish mate in harems and are sequential hermaphrodites, with many changing from female to male as they age. (And they change colours and patterns when they do this.) I’m so glad I didn’t have to sex the individuals for my study.

Finally, there’s their Cinderella dress code. Every night, certain species of parrotfish envelop themselves in a transparent cocoon made of mucus secreted from an organ on their head. Scientists think the cocoon masks their scent, making it harder for nocturnal predators, like moray eels and sharks to find them. It also keeps them safe from attack by blood-sucking parasites.

And here’s something I love about them: on night dives, which we went on just for fun, we could get so close to these sleeping beauties – we could touch them and they wouldn’t move an inch. No reef herbivores are active during the night. Safe in their cocoons, they sleep.

Every day, as I stepped off the boat after a long dive day to walk back home, a part of these parrotfish stayed with me. After all, the white toe-wriggle-worthy sand under my feet was nothing but years and years of deposited parrot fish poop along with weathered rocks, minerals and fragments of shelled creatures. Oh, and about that lesson: Choose your study subject wisely! And then let them teach you about awe and wonderment.