Endangered Species Day fell on May 19 this year. To call attention to the wildlife we’re most in danger of losing, Nature inFocus has launched a multi-part series on endangered species across India. We’ve chosen to focus on each species individually, by asking a researcher who’s been involved in the fight for their survival to write about them. These aren’t intended to be solely dire missives either – if there’s good news, or a small milestone that’s been achieved in the field, we want to highlight it. If their numbers are inching up with the help of conservationists, researchers, policy makers and nature itself, we want to celebrate this. Here is the fifth story of the series.

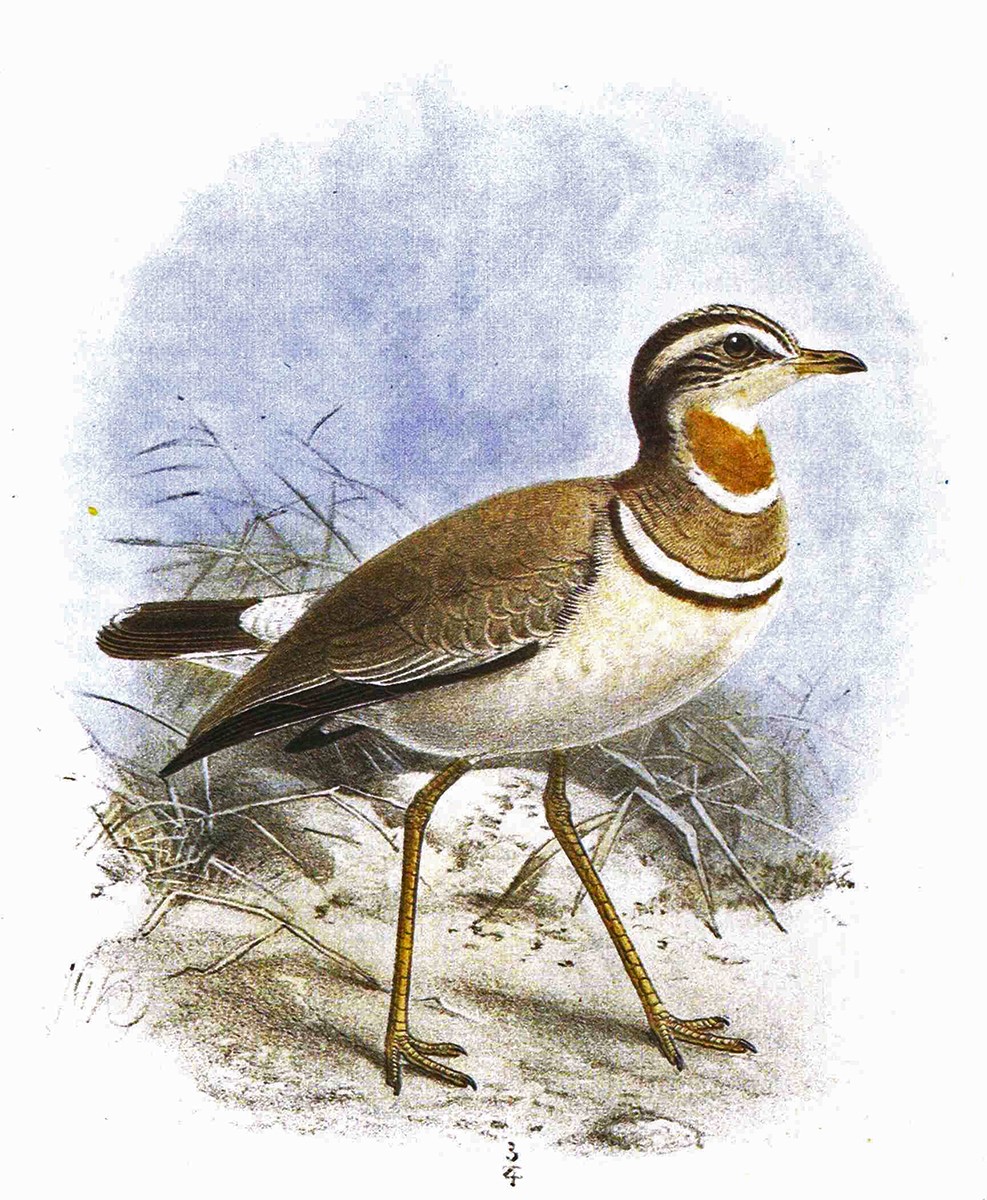

The Jerdon’s Courser is an extremely elusive bird. Jerdon’s Courser is a nocturnal, cursorial bird – it is mostly active at night, and like lapwings and other coursers, it prefers to walk, although it can fly quite well. It is one of three species in the genus Rhinoptilus, with the other two species (Three-banded Courser Rhinoptilus cinctus and Bronze-winged Courser Rhinoptilus chalcopterus) occurring in Africa.

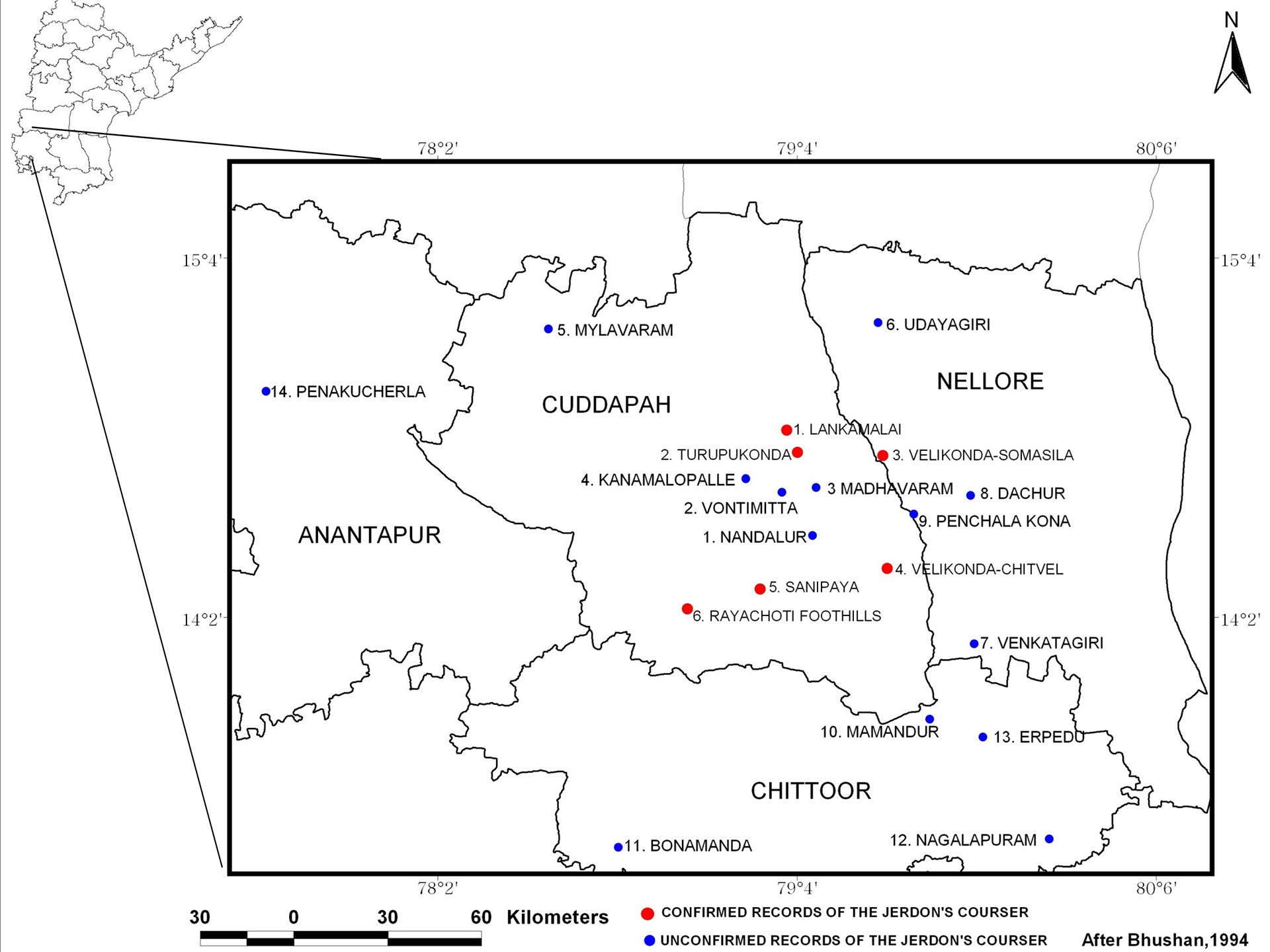

Jerdon’s Courser was first recorded by Thomas C. Jerdon, a British surgeon, in 1848, from erstwhile combined Andra Pradesh. One of the historical records from 1867 placed the bird close to Sironcha, which now falls in Maharashtra; another placed it in the Bhadrachalam region which falls in the newly formed Telangana state. These are the northern limits and there are no recent records from these places. The rest of the historical records are from southern Andhra Pradesh – mainly from Kadapa, Nellore, Chittor and Anantapur Districts.

After 1900, efforts by various ornithologists to record this elusive species were unsuccessful. Special explorations organised by the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) in 1975 and in 1976 in collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution, Washington and The World Wildlife Fund-India, respectively, did not achieve any results. The species was considered extinct until 1986, when BNHS and the US Fish and Wildlife Service initiated a “Study of ecology of some endangered species of wildlife and their habitats”. It was during this project this bird was finally rediscovered by Bharat Bhushan near Reddipalli, in Kadapa district, with the help of a local bird trapper named Aitanna.

Identifying the geographical distribution and finding the Jerdon’s Courser is no easy task. As soon as the bird was rediscovered in 1986 the then-Andhra Pradesh government declared that entire region as Sri Lankamaleswara Wildlife Sanctuary. But only after 2000, based on field research, did we understand that its potentially suitable habitat lies at the foothills of the Lankamalai hill ranges – most of these places were outside the protected area.

Now we know that what kind of habitat it prefers, it is vital to safeguard it. But still, quite a lot of sustained effort is necessary to find this species and to estimate their population. The bird naturally occurs in low densities; it is nocturnal and its calls are not very frequently heard. The only reliable way to find the Jerdon’s Courser is to set up about 20-30 camera traps in a potentially suitable habitat for about a month. If they are around, and if you are lucky, they might trigger your camera.

The Jerdon’s Courser hasn’t been recorded since 2008. It was last seen in Sri Lankamaleshwara Wildlife Sanctuary, Kadapa District. See these location in eBird here. But it has been nearly a decade since the last verified record was made. Searches for this species in the region from 2010 to 2015 did not yield any positive results. But it should be noted that they were mainly concentrated in a few locations and didn’t cover very large areas.

The current situation is pretty dim at the moment. This species, found only in a few locations, was never known to be common. Andhra Pradesh Forest staff have been trained to set up camera traps in the hopes of sighting the courser, and they are conducting surveys in a few locations. However, it may not be extinct yet. There is potentially suitable habitat spread across southern Andhra Pradesh, and I am sure there are quite a few locations where they still persist. But we need to cover more regions. Unfortunately, this is not happening – we need a lot more manpower than we have, quite a lot of camera traps, a huge amount of money and a really committed team to search for this species. It is not easy for research organisations to get funding for such efforts. The Andhra Pradesh Forest Department does conduct camera trap surveys within Sri Lankamaleshwara Wildlife Sanctuary, however they also have limited manpower other priorities too – red sand smuggling is rampant in this region.

Today, it is one of the rarest birds in the world. Jerdon's Courser is listed by IUCN as Critically Endangered – the gravest category, which means that the species is facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild. According to the IUCN, there are thought to be only between 50 and 250 Jerdon's Coursers left in the wild. But it is likely that actual numbers could be much lower.

Habitat modification and destruction have been the main causes of the decline of this species. Unlike the Indian Courser which prefers completely open areas, Jerdon’s Coursers like to be in scrub jungles with little bits of open areas here and there. In 2005, the construction of the Telugu Ganga Canal, a large irrigation canal, destroyed some of the newly discovered sites and probably led to several ecological changes to the scrub jungle habitat. When construction started near the only known location of the Jerdon’s Coursers known to live conservationists and the forest department officials, many organisations such as Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) and WWF-India opposed it. Several conservation organisations and individuals wrote to the Andhra Pradesh government. Several meetings were held; a public interest litigation was filed. The Supreme Court of India asked BNHS to suggest an alternative route for the canal, and in 2008 it was rerouted from its original alignment to safeguard the remaining potentially suitable habitats of the Jerdon’s Courser.

However, pressures on land use have continued, with swathes of scrub jungles at the fringes of the Sri Lankamaleswara Wildlife Sanctuary, Kadapa District, (where the species was known to regularly occur) being cleared for agricultural expansion and monoculture plantations.

Some forest department officials, lacking knowledge about the importance of the species and their habitat, used to plant exotics such as eucalyptus in the open areas and engage in quite a bit of developmental activity such as digging trenches and constructing percolation ponds. This, too, changed the nature of the habitat and made it unsuitable for Jerdon’s Coursers. Although these kinds of activities are not frequent now, it is essential for conservationists to remind every forest official who takes charge of these regions of the consequences of such habitat modification.

There is work being done at the policy level. A lack of ecological information on the Jerdon’s Courser, coupled with increasing pressure on its habitat, has prompted stakeholders to devise a Species Recovery Plan (SRP) to secure the long-term survival of the Jerdon’s Courser.

Based on this plan, various activities are being carried out, such as training courses to show Andhra Pradesh Forest department staff, local tribal communities and volunteers how to use tracking strips and cameras, and how to identify the call to help monitor the species. Based on the plan’s suggestions, some exotic plants were uprooted from a few hectares within the Sri Lankamaleshwara Wildlife Sanctuary. It was also agreed that no further plantations would be planned within any potentially suitable habitat.

One of the most important points within the document stated that if an area of suitable habitat was identified outside the existing protected areas (say, if it lies in a reserved forest), it too should be immediately protected. It doesn’t matter if we find the Jerdon’s Courser there or not. This ‘precautionary principle’ should be applied until evidence of the presence of the Jerdon's Courser is gathered.

We need more eyes to search for this species. And you can help. If you’re a serious and committed birder who wants to help re-rediscover the Jerdon’s Courser, go through the Species Recovery Plan. It is also available in Telugu. Visit its habitat in Sri Lankamaleswara Wildlife Sanctuary and take a look around carefully. Then try to visit the places where it was recorded earlier, in southern Andhra Pradesh. There are a number of sites as shown in this map (you will need to take prior permission to visit if these places fall within the protected area). Observe whether any of those places are similar in habitat to what you saw in the Sri Lankamaleshwara Wildlife Sanctuary. Also, make sure that the habitat is intact in these new sites.

Talk to local people in these regions. Show them photographs of the Jerdon’s Courser and ask them if they recall ever having seen it. Go out in the evening and listen for calls. You will find the call of the Jerdon’s Courser from Wikipedia. Remember it is mainly for you to identify them, not to keep playing in their potential habitat, as there’s a risk that the birds might get habituated to the calls if we play them too often.

To read more stories from the Endangered Species Series, click here.