On a blazing hot summer morning in Denkanikottai, Tamil Nadu, the Bhoomi Farmers team gathered in their conference room. A group of agricultural science graduates with varying backgrounds like entomology, microbiology and agronomy faced a whiteboard as Shankar Venkataraman, Founder of Bhoomi and passionate agriculturist, began the day’s discussion. On the board, he wrote—'It all starts with how you manage soil.'

Over the next hour, Venkataraman spoke about the importance of soil health and how we have become disconnected from this vital resource. But the main protagonists of his narrative were the squiggly lines and circles he drew to depict the life within the soil, a.k.a. soil biodiversity.

The term biodiversity often finds itself in the company of striking images that include colourful indigenous grains, a wide variety of native produce, and floral and faunal diversity both on land and underwater. Amidst all of this is another form of biodiversity which is vital not only for soil and plant processes but also overall human health. Unfortunately, excessive use of chemicals and unsustainable soil management practices have vastly altered and diminished soil's biological agents, making it a matter of concern from an environmental and food security perspective.

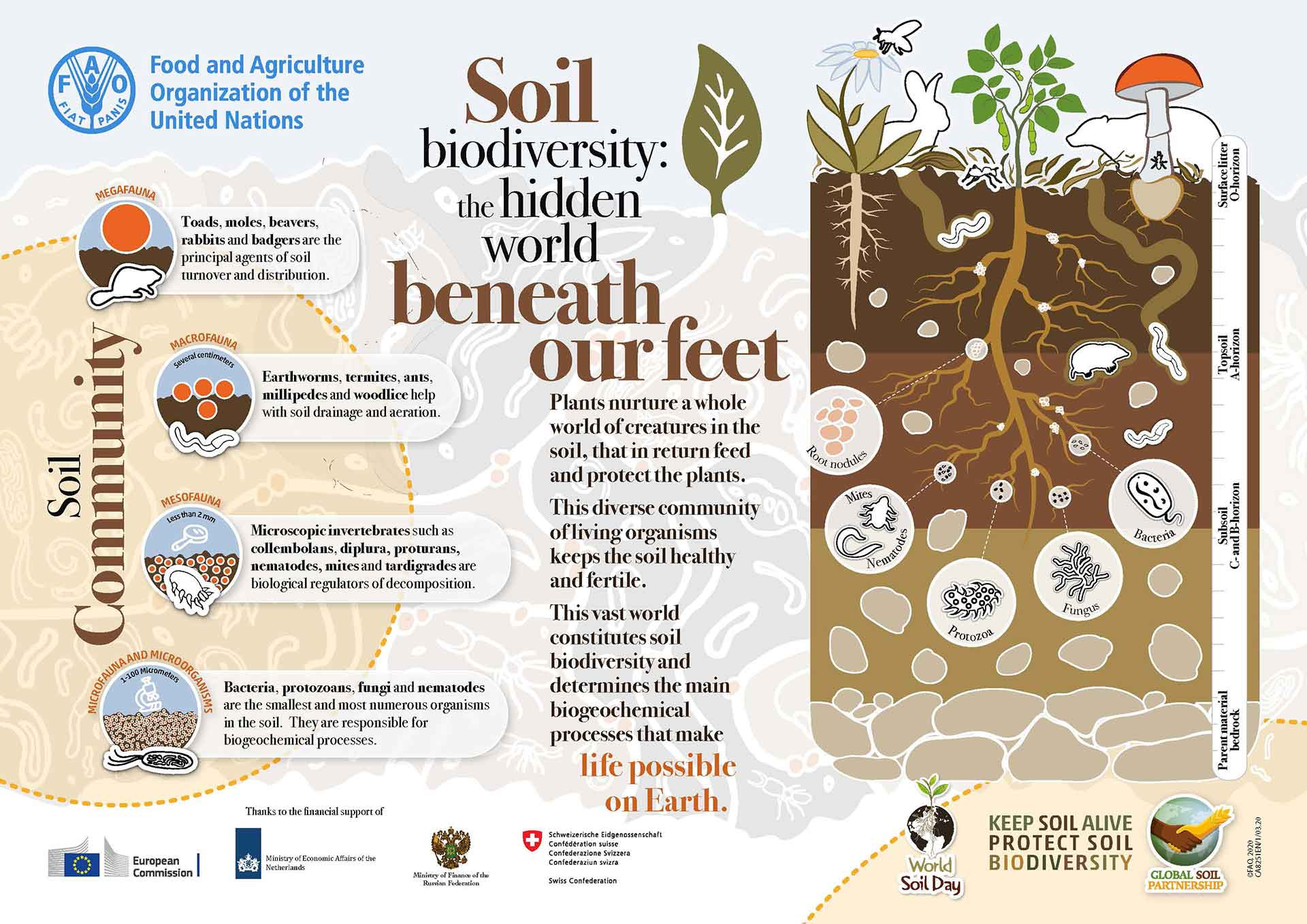

Healthy soils contain a rich mix of microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi, mesofauna (organisms measuring 0.1-2mm in length) such as nematodes and mites, macrofauna (organisms that are more than 2mm in length) such as termites and ants, and burrowing vertebrates such as moles and lizards.

The biodiversity in the soil provides a range of benefits to plants and the surrounding ecosystem, explains microbiologist Dr Raghavendra Rao of Alva's College, Moodabidri, Karnataka. Through his research, Dr Rao is unearthing microbial links to vital processes, such as drought and saline tolerance among crops, as well as their influence on flowering. He adds that soil microbes also produce growth-promoting hormones and enhance the availability of nutrients for plant growth.

The soil biodiversity also partakes in nutrient cycling and protecting the plants from pathogens. But all of these agents need organic inputs for their growth and functioning, says Dr Rao. "We have to give work to soil's living agents, but at some point, we stopped doing so," he says.

Bringing soil to life

In 2016, the first-ever Global Soil Biodiversity Atlas was published by the European Commission Joint Research Centre and the Global Soil Biodiversity Initiative. Apart from highlighting the status of soil biodiversity across the planet, the atlas also focused on threats to soil health like pollution, overgrazing, agriculture, soil erosion, land degradation and climate change. It assigned a risk index for countries based on these stressors. Indian soil was designated with a 'very-high' level risk of potential threats, bringing the soil's invisible agents and the term soil biodiversity itself to the forefront.

At the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), Bangalore, Dr G. Ravikanth, Associate Professor in the Suri Sehgal Centre For Biodiversity And Conservation, is working on a collaborative project that looks at the impact of chemicals on soil's biological components. By mapping the biodiversity in farms that use chemical inputs, Dr Ravikanth's team is comparing the results to farms that have switched to organic cultivation methods over the last one, three and five years.

The research aims to tangibly measure how chemicals harm the biodiversity in the soil and the regeneration that occurs over time when such inputs are stopped. The results of the study are yet to be published, but Dr Ravikanth reveals that chemicals often interfere with the delicate balance between the soil microbes that are beneficial to plants and those that are harmful, often tipping the scale on the wrong side. He explains that improving soil biodiversity also improves its water holding capacity and aids in storing carbon.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Common Ground Report, increasing soil organic carbon (SOC) content by 0.4 per cent annually can contribute to carbon capture of approximately 1 gigatonne per year over the next three decades, mitigating the impacts of the climate crisis. While Dr Ravikanth recommends an optimum SOC content of five per cent, the recently published first digital maps of India's soil properties reveal that the national average is as low as 0.5 per cent.

At Bhoomi, Shankar Venkataraman quotes the SOC levels in Indian soils to emphasise the need for immediate action. Bhoomi's head of research, Sridhar Venkataraman explains that the focus of the farm is to produce nutrition-dense vegetables using a combination of soil science and hi-tech farming. The duo showcase the biological compost that they assiduously developed, keeping the needs of the soil in mind. While Bhoomi is developing similar farms in two other districts in the state, this one will also be their research and development centre, explains Sridhar, where they develop scalable techniques for soil management. Using the no-till approach and employing their in-house mulch, the team ensures that the soil nutrition is retained for all the beings that depend on it, including humans.

Reversing the clock

Soil biodiversity is an intriguing topic. Information on it is scarce and the biological members of the soil world remain shrouded from human eyes, making it hard for us to envisage an outcome where they play a role. But, activist P. Srinivas Vasu, who has been working in this field for the past decade, believes that the right communication can make all the difference.

Popularly known as Soil Vasu, he runs a non-governmental organisation, also named SOIL (Sustainable Organic Initiatives for Livelihood), which aims to educate farmers on the importance of soil health. Armed with posters written in the regional language Kannada, Vasu works with farming communities aiding them in improving their soil processes. While testing the entire gamut of soil biodiversity using DNA sequencing and other techniques can cost up to ₹25,000 per sample, Vasu's methods are more accessible to farmers.

"Soil that is rich in biodiversity is first of all dark in colour,” he explains. “It also has that distinct earthy smell, and when you hold it between your fingers, there will be no sharp elements in it. When you hold the soil in your hands, it will feel light and when you drop the soil, there will be no dust. You will find bits and pieces of leaves and other plant materials, and you will see insects and other life forms."

He reveals another method in which soil is mixed with water and left undisturbed in a jar. The organic content will become visible as the top layer after some time.

While the tests may seem simple, the process of changing the approach to a bottom-up one is not. A lot of the reluctance comes from the fact that transforming the soil is a labour-intensive task, explains Vasu. "When we talk about natural methods, we expect the seniors in the village to agree with us. Unfortunately, they are also used to conventional farming methods now and they are worried that what we recommend is a lot of work for their family members.”

Harish Manoj Kumar is all too familiar with this sentiment. When he took over the farming reins from his father, a conventional farmer, he knew that he would do away with chemicals. But, the process of changing the soil on his farm in Pollachi, Tamil Nadu, has been a slow and arduous one. "It's not like one fine day you just stop chemical inputs,” he says. “You need to phase them out while building practices that are best suited for your soil."

Kumar's efforts over the last decade have led him to develop India's first tree-to-bar chocolate, Soklet, with the cacao grown in-house. Standing in the middle of his farm, he points to the large pile of discarded cacao shells. "This is not waste," he says. The cows on his farm will soon spend some time trampling these shells and munching on them while adding their dung to the decomposing milieu. The mishmash will make its way back to the farm's soil.

"If you want life within the soil, you need life around it too," says Kumar. In the backdrop, a cacao tree stands tall, bearing healthy pods and flowers. A web of fungi adorns the base of the trunk while ants swarm around it and a carpet of dried leaves hide the soil beneath.

Awareness and education

Although a discussion on soil biodiversity seems to spiral into a debate on conventional vs organic farming, the reality is that it runs deeper, touching upon the role soil plays in our life. As people working in this sphere unanimously quote—'soil health is our health'.

Understanding the complexities of soil life requires time and effort, and Vasu strongly believes that demonstration plots are vital to change the way people approach soil. The Punarchith Collective in Karnataka, for example, has worked on a land restoration project called Angarike Maala (Meadow of Dodonaea) where they have transformed a degraded patch of land in Nagavalli village, Chamarajanagar district. The 'Living Lab' that they have established highlights the consequences of improved soil conditions. Vasu is one of the core team members of Punarchith. He also emphasises the need to encourage a community approach to build resources for soil regeneration.

Environmental scientist and educator, Dr Radha Gopalan shares that the need of the hour, though, is to start early. In her paper, Getting to the Soul of Soil, she reveals simple activities for school children to enhance their understanding of soil biodiversity beyond the presence of earthworms, as commonly cited in textbooks. Having worked with children from rural and urban backgrounds, she firmly believes that there is a disconnect in how young minds perceive soil. "The common conception is that soil is an inert substance and that needs to change. The role of microorganisms in building, nurturing and sustaining soil needs to be the focus," she says.

Back at Bhoomi, after the lecture, the team is getting ready to head to the farm and begin their activities for the day. On a table opposite the whiteboard, a large glass bottle reveals a brownish-white sponge-like substance. The label on the bottle informs its audience that these are the indigenous microorganisms sampled from a particular tree on the farm. It looks like the biodiversity in the soil has finally found a seat at the table.

This story was produced with support from Internews's Earth Journalism Network Biodiversity Grant.

References:

Larbodière, L., Davies, J., Schmidt, R., Magero, C., Vidal, Arroyo Schnell, A., Bucher, P., Maginnis, S., Cox, N., Hasinger, O., Abhilash, P.C., Conner, N., Westerberg, V., Costa, L. (2020). Common ground: restoring land health for sustainable agriculture. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. WWF. 2018. Living Planet Report - 2018: Aiming Higher. Grooten, M. and Almond, R.E.A.(Eds). WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

WWF. 2018. Living Planet Report - 2018: Aiming Higher. Grooten, M. and Almond, R.E.A.(Eds). WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

Nagarjuna N. Reddy, Poulamee Chakraborty, Sourav Roy, Kanika Singh, Budiman Minasny, Alex B. McBratney, Asim Biswas, Bhabani S. Das, Legacy data-based national-scale digital mapping of key soil properties in India, Geoderma, Volume 381, 2021, 114684, ISSN 0016-7061, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2020.114684.(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016706120309861).

Radha Gopalan, (2018) Getting to the soul of soil. i wonder (4). pp. 58-62.