Photographs by Umeed Mistry

It was a cold and windy December afternoon in South Andaman. I was out at sea, collecting data for my master’s research project. My dive buddy and I ascended to the surface after two long dives surveying the coral in Allen’s patch. We were shivering, tired and waiting to get out of the water. Just as we climbed into the boat, our captain spotted the slender, black fin of an animal slap the water’s surface. Within seconds we all noticed at least three or four pairs of these fins, fairly close to our boat. Even though I had not seen anything like this before, I knew instantly what we were looking at. Forgetting the cold and fatigue, we quickly jumped back into the water and swam in their direction. Before we knew it, we were swimming with manta rays.

I have seen a manta ray about three or four times since that day, five years ago. And yet, each time I struggle to find words to describe the experience of sharing space with this animal. I grapple for adjectives and end up gushing like a starstruck lover, often surrendering to a defeated ‘awesome’!

This feeling seems to be universal. Most people who have encountered a manta will agree that words do no justice to the feeling of being in its aura. Imagine an animal that must constantly be on the move, for water to flow through its gills, for it to breathe. Imagine an animal, a fish, which likes to breach the surface of the ocean into our atmospheric world, sometimes tossing and tumbling, before it dives back in. A fish so big, it casts a giant shadow as it glides past.

Of the two species of manta rays in the world, the Reef Manta (Manta alfredi) grows to about 3.5 metres from fin tip to tip, weighing up to 1.4 tonnes. The Oceanic Manta (Manta birostris) has been recorded to grow as much as 7 metres across, weighing up to 2 tonnes. This animal is a giant. But a gentle giant, who often entertains requests by shelter-seeking hitchhikers like juvenile fish and remoras, literally taking them under its wing as it travels through the tropical seas.

Although a manta is capable of achieving great speeds (bursts of up to 22 kmph), it usually moves very slowly, especially when hunting. Sometimes, they flap their wing-like fins together like a bird, and sometimes they glide along like a sinusoidal Mexican wave, rolling each fin one by one. It is when you watch a manta handling a current that you really become aware of its strength. In a current so strong that us humans would have to hold on to a boulder or kick violently to keep from being swept away, a manta will show no sign of effort or strain to hover motionless, headfirst in the current.

Mantas also make the best of currents. Rays, in general, are flattened fish with mouths on their underside to feed on bottom-dwelling crustaceans and other hidden critters. But not manta rays and their mobula ray cousins. These beauties have evolved mouths that face forward, to engulf large quantities of microscopic plankton suspended in the currents that they swim through. Instead of teeth, mantas use gill plates or gill rakers. These look like a row of hooks and are used to sieve out plankton from the incoming water. This adaption to ‘filter feeding’ and life in mid-water makes manta rays and mobula rays very unique in the ray family. Manta and mobula rays also lack venomous sting barbs at the base of their tail, making them even more distinct from sting rays.

In pursuit of food, Oceanic Mantas will go on excursions of up to 500 kilometres at a time, or on deep dives anywhere between 100 to 400 metres down in the ocean. Scientists speculate a ‘retia mirabilia’ (in Latin, a ‘wonderful net’), a network of arteries and veins keeps a manta’s brain warm during deep dives, where temperatures rapidly plummet (from 28 to 30C at the water’s surface to less than 10C).

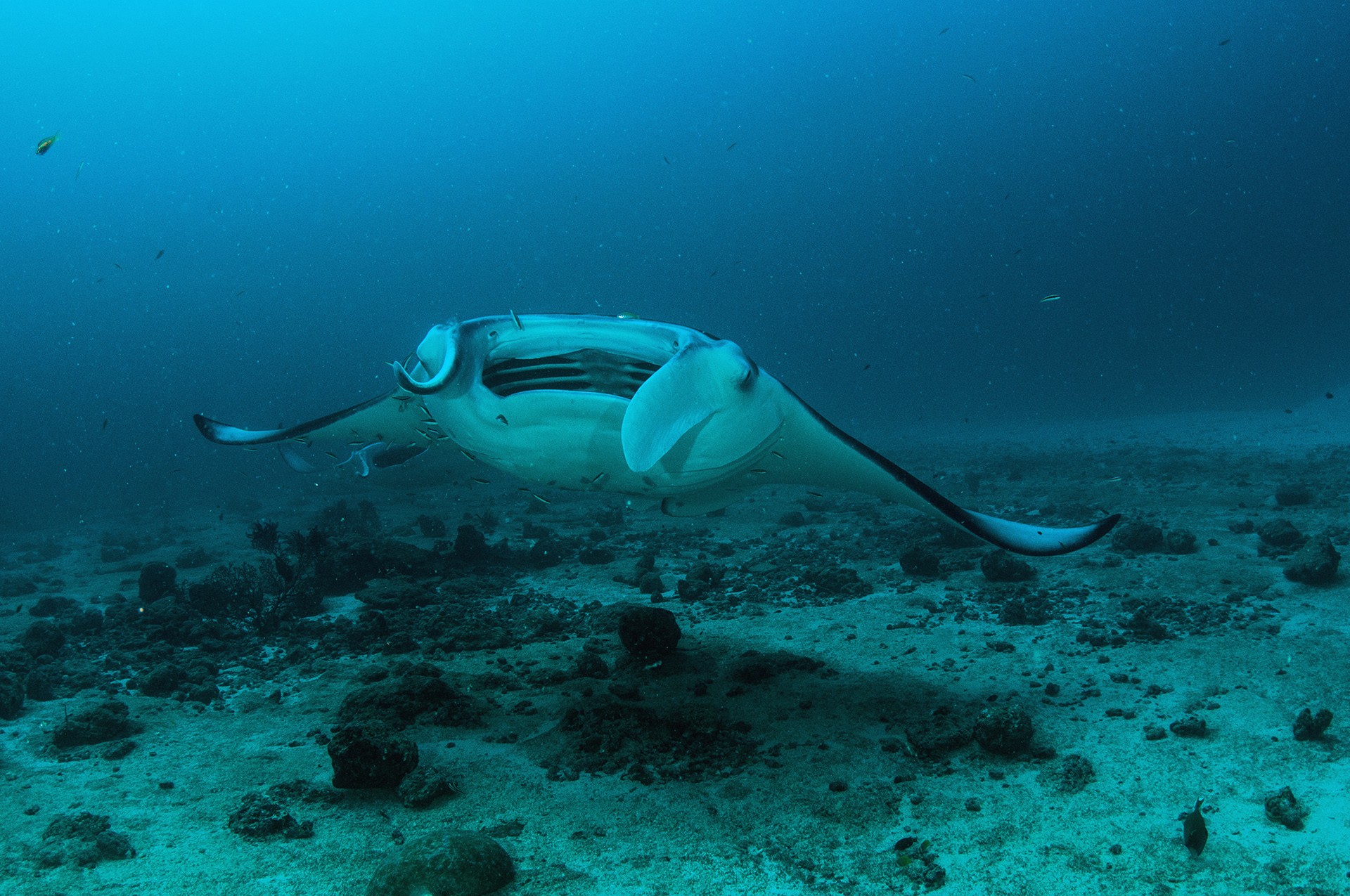

When manta rays do visit shallow coral reefs, apart from food, what they are looking forward to is a good clean. They search for cleaning stations that are usually always open for business, set up by enterprising small fish called wrasses that are looking for a source of food. And mantas have favourites! They are known to frequent particular cleaning stations more than once, to get rid of parasites, and clean out wounds or sore patches left by piggybacking remoras. Mantas do this frequently to avoid infection even though their bodies are coated in a thin protective mucous. Although both Oceanic and Reef Mantas visit cleaning stations, it is the latter than do so more often. It is beautiful to observe the mutual exchange between the cleaner and customer unfold. A manta will submit itself to cleaner wrasses like a car to a car wash. And tiny hungry fish are provided full entry – around the eyes, into the gills and gill plates, above the tail and under the belly.

Reef Manta Rays are known to be quite social with other individuals of its species, while their oceanic counterparts are thought to spend much of their time scoping the seas in solitude. When mantas do come together, it is usually during large blooms of plankton. They aggregate in large numbers, often in very shallow water, tunnelling volumes of plankton between their cephalic fins (head fins). In fact if you are in the Maldives, a mask and snorkel are enough to fetch you front-row tickets to some phenomenal manta feeding frenzies.

Even more spectacular, but rarer to witness, is manta courtship. During the breeding season, large females are courted by as many as twenty small males who wait for her at her favourite haunts – usually cleaning stations on coral reefs. A female manta will race around a reef for hours before deciding who among the many hopeful males in her ‘mating train’ she will choose. She will spin and roll, twist and turn, sometimes leaping out of the water, to test the strengths of her potential suitors.

Manta breeding being rare to witness may have something to do with the fact that females are estimated to become pregnant once every five or six years. Each time, they take nearly a year to give birth to a single pup. Even though Reef and Oceanic Manta Rays are thought to live several decades (20 years at least), like humans, they take at least 10 to 15 years to sexually mature and stand a chance to reproduce. This is what we know of Reef Mantas. The reproductive lives of Oceanic Mantas are still a mystery. Oceanic Manta Rays spend most of their time out in the open ocean, and very little in places that are easy for us to get to. Despite this, today Oceanic and Reef Mantas have both become prized targets for fisheries across the world.

Caught as incidental bycatch in fishing nets until a decade ago, today manta rays have replaced previously sought-after fish species whose stocks stand too depleted to target for meat anymore. There has also been a rather disturbing increase in what the world now knows as an international ‘gill plate trade’ for Chinese medicine. India and Sri Lanka are its leading exporters. Manta rays are fished for their plankton-straining gill plates, which are dried, powdered or turned into soup as alleged antidotes to skin rashes, chicken pox, asthma and cancer, among many other ailments. There is no evidence in modern medicine to suggest that these antidotes actually work. Today both manta ray species are listed as ‘vulnerable’ in the global IUCN redlist, with an estimated 30 percent decline in their populations worldwide.

Despite their almost bizarre appearance, shape and size, manta rays have won over the hearts of people worldwide. People will travel halfway across the globe just to swim with mantas in the wild. These are highly intelligent animals with the largest brain to body mass ratio of any marine fish, seen to be capable of curiosity, recognition and memory. Tourism also has a positive impact on manta ray conservation, providing avenues for education and awareness, supporting the local economy, research and management.

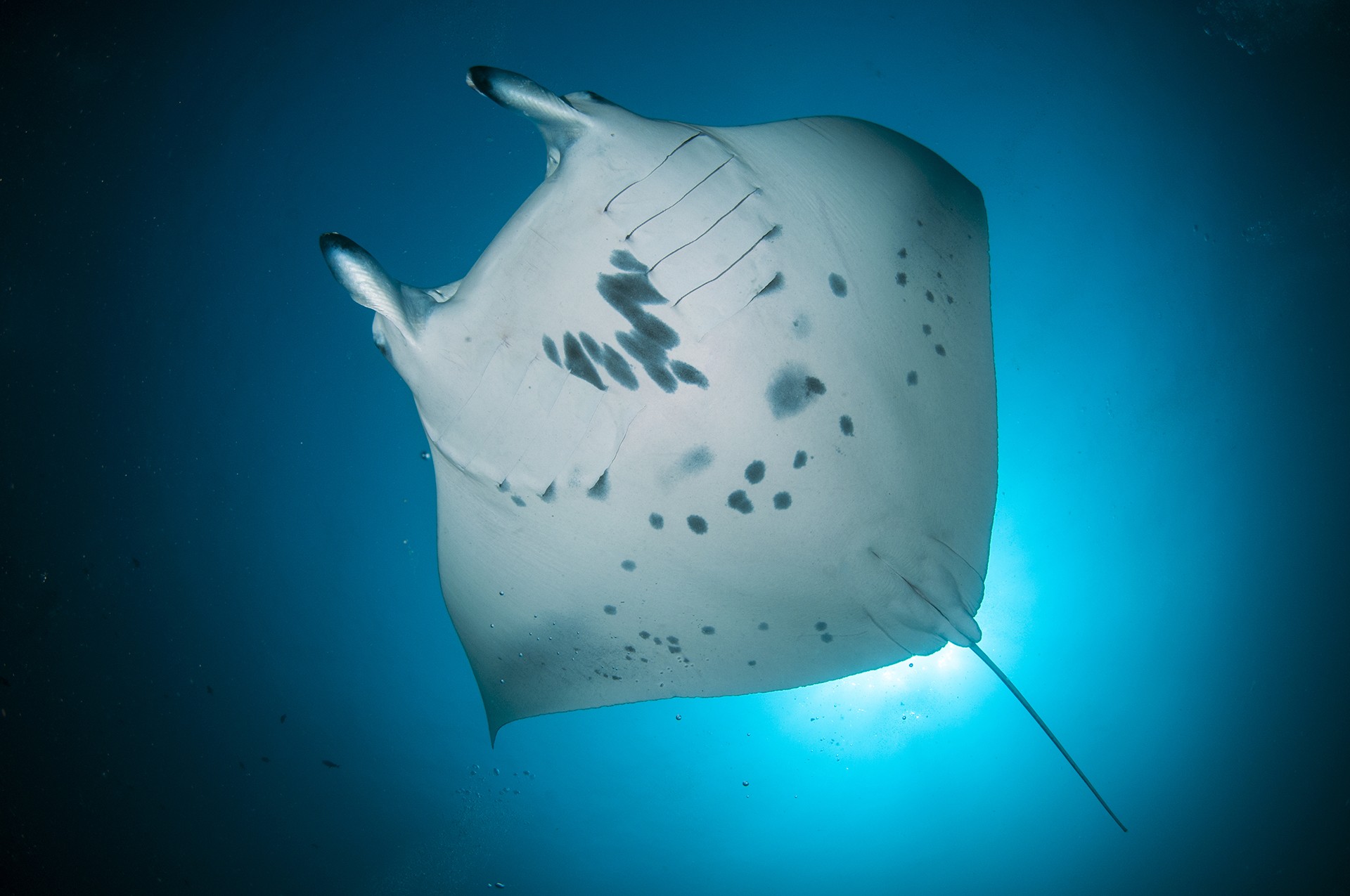

Several conservation organisations are actively harnessing the widespread passion and concern for manta rays towards their protection. For instance, Manta Matcher and IDtheManta are two global databases that are used to identify and record individual manta rays worldwide using the unique patterns of blotch-markings on their bodies. Each image becomes a record for one unique individual. We could potentially track migratory routes and destinations (based on the different locations a particular individual has been sighted and photographed), population dynamics, global distribution and hotspots for conservation. Thousands of images of manta rays are now making their way online, thanks to tourists and divers worldwide. Contributing to such citizen science initiatives will significantly scale up the reach that manta conservation can have.

While the biology of manta rays – slow maturation times and infrequent pupping – might point towards a bleak future in the light of the ongoing fishing onslaught, there is still hope to conserve these magnificent species. I hope that everyone gets a chance to see a manta ray someday, an experience that promises to be nothing short of magical.