Kotagiri is a small town near the hill stations of Udhagamandalam (Ooty) and Coonoor in Tamil Nadu. It is situated next door to the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, on the northeastern crest of the Nilgiri Plateau. The area largely consists of vast tea plantations and agricultural lands interspersed with fragmented forest patches.

As per the 2011 census, the Kotagiri taluk had eleven villages with a combined population of 66,094. The region is the abode of Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGS) like the Todas, Kotas, Irulas, and Kurumbas, its original inhabitants. Besides them, Badagas, Sri Lankan repatriates, Malayalees, and settlers from other parts of the state currently reside within the taluk. These diverse communities engage in farming and cultivation and find employment in plantation and household industries. In addition, people also migrate to lowland cities such as Coimbatore and other nearby areas for work.

In recent years, it has become common to witness wild animals such as bears, leopards, porcupines, gaurs, wild dogs, and jungle cats in different parts of Kotagiri, particularly in residential areas. A recent report from Mongabay-India states that deforestation, agriculture expansion, infrastructure development, and climate change are some of the factors pushing these wild animals out of the forests. They gravitate towards human-dominated landscapes due to easy access to food sources such as crops, food waste, and livestock.

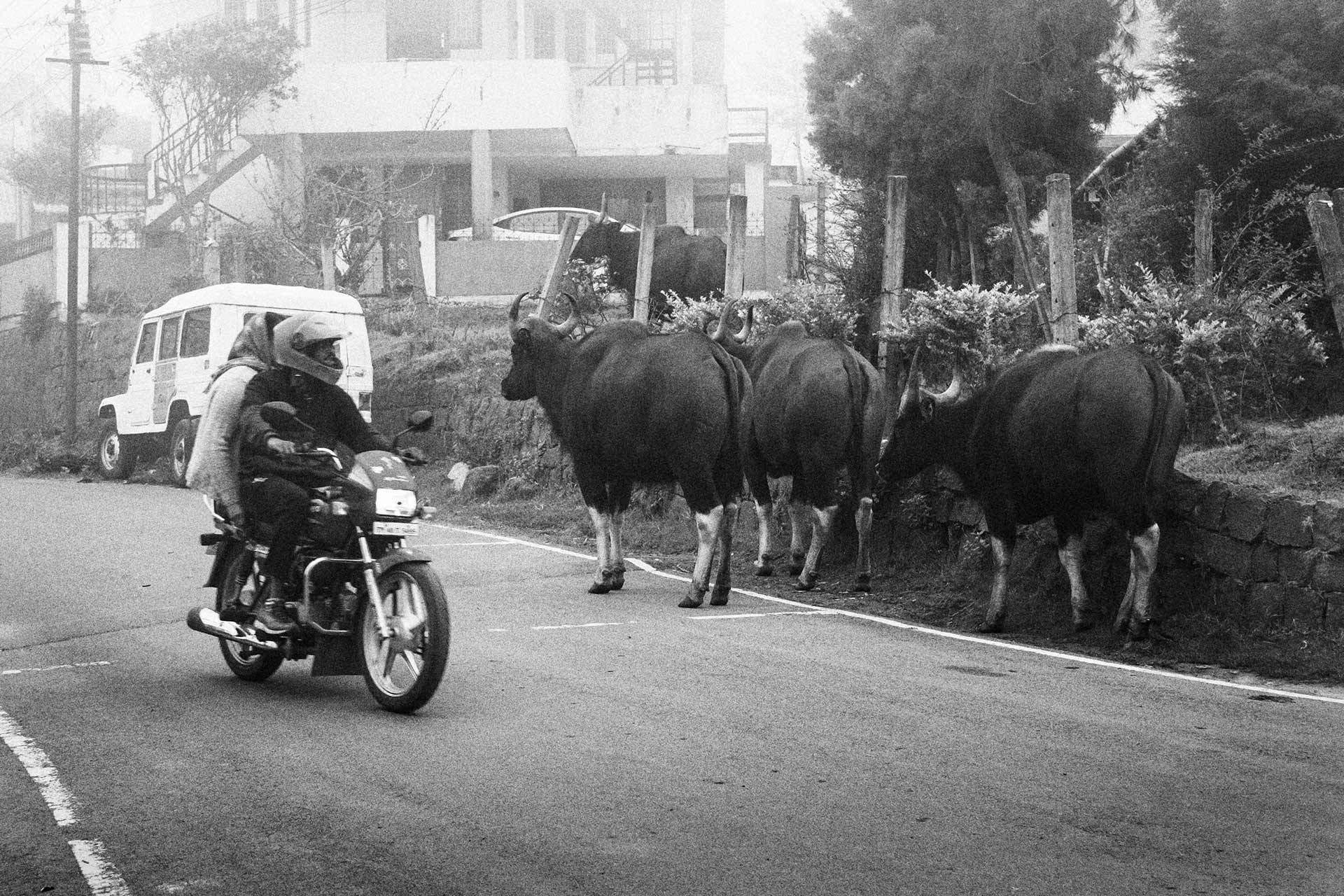

The Indian Gaur (Bos gaurus), family Bovidae, is one of the largest wild ungulates found in Asian forests. They have been listed as vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List since 1986 and are a Schedule I species as per the Wildlife Protection Act (1972). Studies show that gaurs are naturally very shy and avoid human-use areas. But, in recent years, in Kotagiri, Coonoor, and other parts of the Nilgiris, it has become very common for people to see gaur herds grazing in residential neighbourhoods and tea plantations. In Kotagiri, gaurs are habituated to human presence and vice versa. They graze, mate and sleep in the vast tea plantations, and even walk into towns and markets.

Gaurs in Human-use Landscapes

Gaurs are both grazers and browsers, feeding on a large variety of plant species. They mostly eat grasses and shrubs. An increase in invasive plant species and fragmentation of grasslands have reduced the availability of fodder inside forests, forcing gaurs to move into tea plantations and other human-inhabited spaces for food. While grazing in the tea estates, they eat only the grass amidst the tea plants and not the tea leaves. They visit the villages and feed on plants, weeds, and grasses near the houses. In addition to this, they also consume the crops and vegetables that are grown by local farmers. Furthermore, the local people indicate that over the years, gaurs in Kotagiri have gradually started to include cooked food waste, particularly vegetable waste, in their diet.

Another reason gaurs might prefer human-inhabited areas is for protection. Tribal communities believe that prey animals approach human settlements to protect themselves from predators. Additionally, poaching regulations have significantly increased the gaur population over the years while reducing their fear of humans.

A common belief among the local people about the origin of these wild bovids is that gaurs are domestic cattle that got lost in the forests. This perspective is not specific to one particular community in the landscape but is prevalent among native tribal groups and settlers who came here 40-50 years ago. The Irula tribal communities from specific villages in Kotagiri even perform a community play called Doddu Aatam (Gaur Play), a traditional performance that portrays their cultural relationship with gaurs.

The residents of Kotagiri exert minimal effort towards their peaceful coexistence with gaurs. They follow certain safety measures, which include:

- Carrying a flashlight whenever stepping out at night

- Elderly people refrain from stepping out at night

- Leaving for work earlier to avoid encounters

- Pausing to allow gaurs to pass

- Not disturbing the gaurs in any case

- Temporarily relocating work activities to alternate locations within the estate when a herd is present in a specific area

Mutual Respect and Fear

In Kotagiri, a relationship based on fear and respect has allowed for the sharing of space. At times, other wild animals like leopards, bears, porcupines and wild dogs also enter residential areas in search of food and prey, but the local people treat them differently. With gaurs, locals feel that they are gentle and harmless beings; they come only for food and water, and they don't harm anyone unless provoked.

Over the years, through observation, the residents have a thorough awareness of the behaviour of gaurs, fostering a sense of caution and respect. People are aware that even though gaurs are increasingly present in human-dominated environments, they are still wild animals. They fear, "What if the gaur attacks us if we go nearby? What if the gaur charges back if we throw stones at it?” Similarly, the local people believe gaurs experience fear when they are approached by humans, “What if they take away our calves? What if they attack us?” Gaurs and humans always keep a safe distance from one another in this shared landscape. Fear acts as a key to mutual avoidance. This shared sense of caution helps maintain careful harmony, enabling gaurs and humans to coexist in the same area.

The Other Side

In recent years, there have been some negative human-gaur interactions, which have even led to a few casualties. However, these incidents are relatively rare. Gaurs sometimes wander into farms and damage crops, especially when the fields are poorly secured. Their presence in tea plantations also disrupts work. Moreover, people feel afraid to go out at night, even to nearby places. There have been instances where gaurs have damaged property, such as buildings, compound walls and vehicles. Human deaths and injuries have also occurred as a result of gaurs resting inside tea plantations, showing only their horns and a part of their face. If a person accidentally gets too close, the gaur may get scared and attack.

Kotagiri, just 28km away from Ooty, is also starting to get popular among tourists as it is less crowded. The tourists’ perspective of gaurs, however, differs from the locals. Tourists initially mistake them for domestic buffaloes and when they realise they are gaurs, they get excited and sometimes get too close to take photos or selfies. This can scare the gaurs and lead to unfortunate attacks. The local people are known to hold a belief that if a gaur cannot retaliate immediately, it will carry forward the memory of the incident and end up harming someone else instead, which is more likely to affect residents rather than tourists who stay there for a short period.

Going Forward

Once limited to forests, these timid bovids now live in human-dominated spaces, as a result of diminishing wild spaces and an increasing local population. According to studies, environmental changes have already prompted 50 per cent or more of all species worldwide to relocate their geographical ranges to seek more favourable habitats. This mass migration of people and wildlife highlights the importance of alternative and intersectional approaches to conservation. One of the key elements influencing coexistence in the Kotagiri landscape is the local peoples’ perceptions of gaurs. Similarly, shared spaces in the long-term can be fostered by strengthening the knowledge management system, facilitating effective engagement of local communities and stakeholders, raising community awareness, restoring grasslands in specific areas, and implementing sustainable garbage management systems.

This story was originally published on March 12, 2024, in Current Conservation.

The article is based on the findings from the Human-Gaur Relationship Project, which is a part of the Nature-Culture Fellowship by the Wildlife Conservation Society-India in 2022-2023. The project was funded by Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies, and the fieldwork was supported by Keystone Foundation. The author would like to thank Sahamatha for her support in the development of this article.