Sure, there’s a wealth of flora and fauna to seek out in our sanctuaries, reserves and jungles. Wildlife enthusiasts will always be drawn to, well, wild spaces, but in the quiet time between each adventure, we should remember there’s a wide range of fascinating biodiversity to encounter in our cities, too. Through this new series, we encourage the Nature inFocus community to explore our urban biodiversity, to notice the often-overlooked creatures in our midst, and to appreciate their fascinating ecology and behaviour. Each story will focus on a single species representing different taxa, and will be illustrated by a different artist. This is the second story in the series. Look out for the next instalment, all about the Blue Pansy next month.

If you walk by a waterbody in your city – a lake, a canal or a river even, try and observe the plants along the edges. You might find that the leaves sometimes show cuts and holes, an uneven lattice breaking the immaculate symmetry. If you look closely, you may encounter an insect with a hard shell-like covering (exoskeleton), heartily devouring the leaves. This, then, is Aspidimorpha miliaris, a stolid member of the beetle world.

These beetles, found across Asia, belong to a peculiar group called Cassidinae that resemble ancient war helmets in appearance. Often referred to as Tortoise Beetles due to their oval and dome shape, they display diverse patterns and colours. In A. miliaris adults, the hardened outer wings (elytra) are initially transparent and gradually transform to a dark orange-red shade. Simultaneously a pattern of black spots develops on the body. Sometimes, individuals or even an entire population of A. miliaris can exhibit a good deal of variation with respect to colouration and in the number and pattern of black spots – that is, they display multiple colour morphs.

A. miliaris is one of the larger Asian species of Cassidinae, growing up to 15 mm in length. This species occurs throughout the year but is most commonly seen during and after the monsoon season. (So it’s a good time to look out for them the next time you’re out and about near a waterbody.)

These beetles, as those nibbled-on leaves might have hinted at, are wholly herbivorous. They often feed on Bush Morning Glory (Ipomoea carnea Jacq.) plants, commonly known as ‘Besharam’ (in Marathi) or ‘Behaya’ (in Hindi). A known weed, it grows abundantly along marshes and waterbodies. Though the beetles are tiny, they make their presence felt by their huge numbers. A.miliaris feed so voraciously on the green leaf tissues that they can ‘skeletonise’ the plant. At times, their population is so abundant that on a single six-foot-tall plant, there may be more than 50 larvae, about the same number of pupae, and 15-20 adult beetles present. That’s why they have been suggested as bio-control agents for this weed.

A. miliaris females lay 32-80 eggs in specialised protective chambers called ‘ootheca’. The larvae that emerge have an interesting set of strategies to protect themselves from predators. For example, they devise a structure to function as a sort of mobile scarecrow by piling their own shed membranes and faecal matter onto spines attached to the rear end of their bodies. This defensive shield is carried flat overhead on the larvae, and can also be used to lash out in defense when they are attacked by a predator. In addition, the faecal matter and shed membrane are thought to contain noxious chemicals that repel predators. And of course, another advantage of using faecal matter is that it can be easily replenished. This behaviour, unique though it may seem, is also seen in some related groups of beetles.

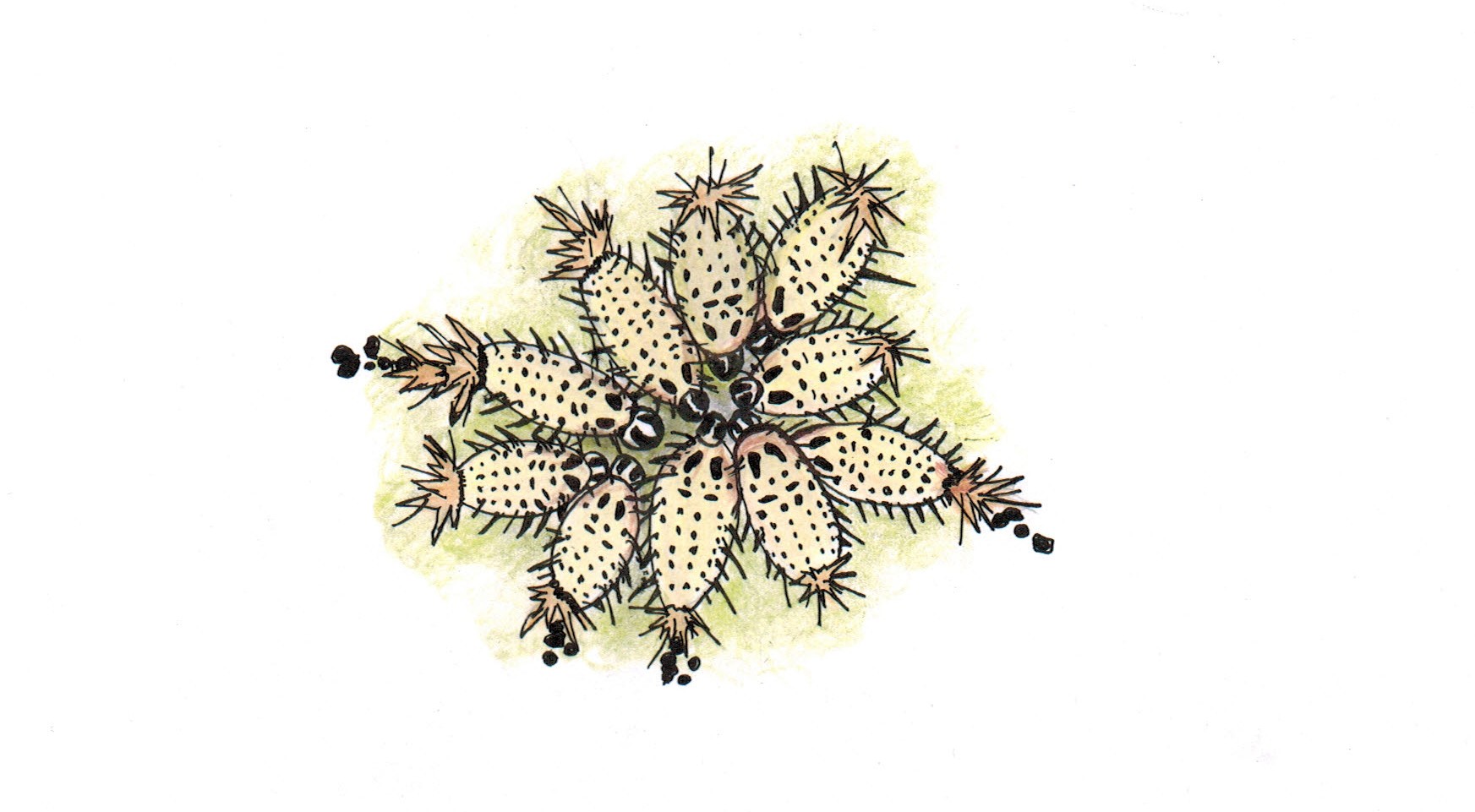

Another preemptive passive defense strategy is called ‘cycloalexy’ which is often employed while the larvae are resting. The larvae form groups by gathering in a closed circular pattern with their heads in the centre and tails at the periphery. In this setting, they perform coordinated movements to adopt a threatening posture to repel predators such as ants, true bugs and parasitoid wasps. This behaviour has been reported in various Cassidinae species around the world but in India, it has been observed only in A. miliaris.

Adult beetles too have their own way to protect themselves when attacked. If they are disturbed, they retract their claws inside their helmet-like elytra and clamp strongly onto the leaf surface. The adhesive pads and bristles on their legs and their sharp claws ensure their grip is firm, making it difficult for the insect to be pulled off by an invertebrate or other predators. Sometimes an escape strategy is used too – beetles will often free-fall upside-down onto the ground, playing dead.

So now you know, apart from its eye-catching beauty, A.miliaris displays fascinating ecology and behaviour as well. The next time you walk past a thicket of Bush Morning Glory, make sure to turn over a fractured leaf and watch this beetle in all its glory instead.

Last month, we wrote about Weaver Ants. Read the story here.