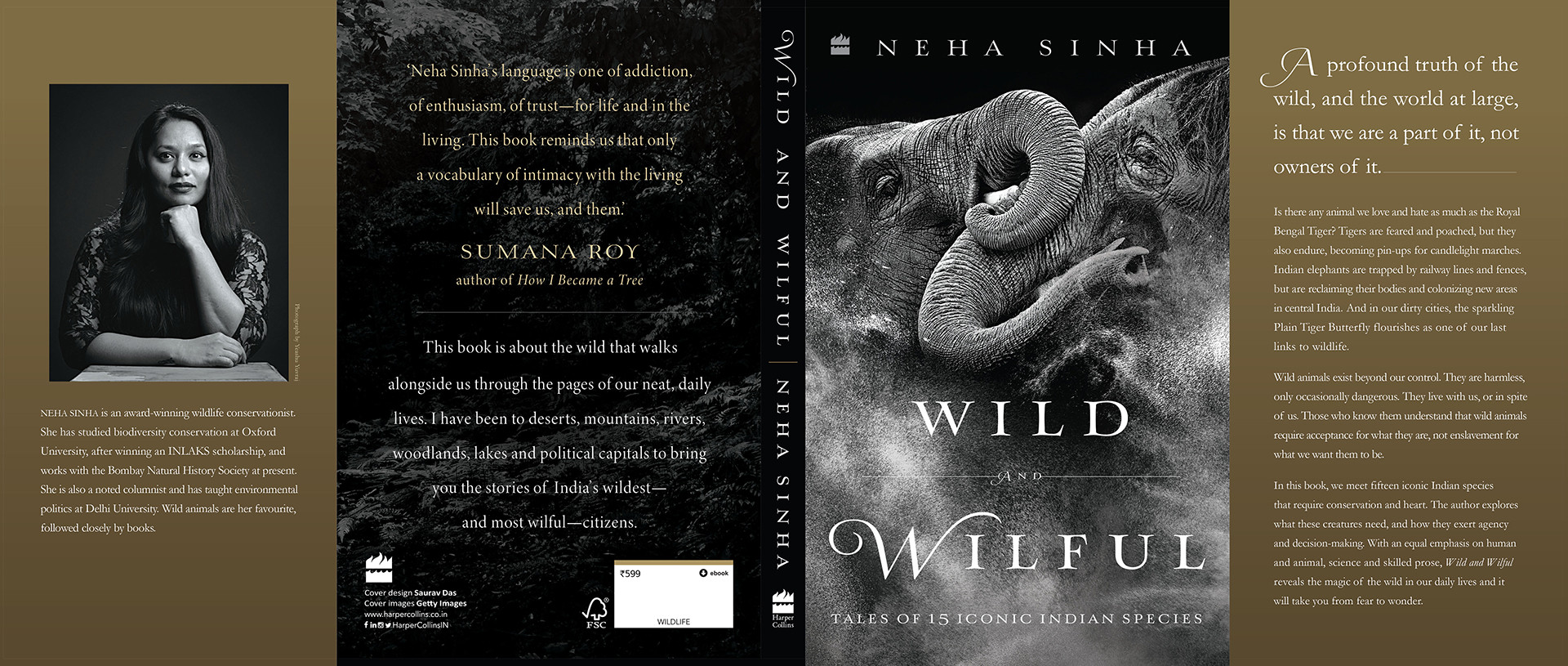

Wild and Wilful – Tales of 15 Iconic Indian Species by Neha Sinha is a collection of essays on 15 species from the Indian wilderness, exploring the challenges facing these species, the latest ethical and scientific developments, and our responsibility to these animals.

With an equal emphasis on human and animal, science and prose, Wild and Wilful reveals the magic of the wild in our daily lives and shows us what it can teach us about humanity. Neha Sinha is a conservation biologist with a vast experience in environmental policy, and she writes about the wild in a language that possesses the power to take you from fear to wonder.

Read about the successful incubation of Great Indian Bustard eggs in the world’s first conservation breeding centre in Rajasthan, the repopulation of Sariska with tigers after their local extinction, the fascinating success story of saving Amur Falcons in Nagaland, and so much more.

Published by Harper Collins Publishers India, Wild and Wilful will be released on February 10, 2021.

This is an excerpt from the chapter, 'The Leopard and the Cockroach'.

***

The photos of the Leopard were soon in the papers. Nature lovers were ecstatic. Debates on rewilding larger parts of the city started ricocheting through its corridors. Could Delhi reclaim older habitats, and raise forests, reedbeds and scrubland next to the entire length of the river Yamuna? Could it have leopards loping once again through the Ridge forests, which are marked with ancient Aravalli boulders, but ring with a resounding silence: the absence of megafauna and large predators? There had been leopards in Delhi before too, pushing from both ends of north and south Delhi, brushing other states. But they always slipped away from public memory or planning. Pugmarks had been found in a mushroom farm near Wazirabad before. But this time Delhi’s Leopard was on camera—immortalized, framed and recorded.

It was also perfect to be judged.

The first wave of protests came from people who lived next to the park. In no time, the group had made representations to the Aam Aadmi Party-led Delhi government. The demand was clear: remove the Leopard or lose support. Imran Hussain, the then environment minister of the AAP, made clear, unequivocal statements on the issue. The Leopard was going to be caught and moved either to a ‘forest’ or to a zoo. A cage with a goat as bait was set up.

This was declared as being done for the safety of the people, and the safety of the Leopard.

The chief wildlife warden of the city stated that the Leopard might have been ‘separated from its pack’. My response should not have been one of shock, but I felt surprised all the same. The image of the Sohna Leopard—the hissing spitfire, unforgiving and fearless—came to mind. Everything that was being said reeked of what can only be described as ecological illiteracy. Leopards are elusive, secretive and solitary. They don’t live in packs. The only big cats that live or move together are lions. And the minister’s statement that the Leopard was going to be caught for its safety made me choke. The last thing a wild leopard’s safety needs is capture. Catching a wild leopard may maim it forever—through a botched operation, or the animal’s fury at being touched by human hands.

I requested a meeting with Imran Hussain to convince him to drop the idea of Leopard capture.

In a room with white furniture, talking to the white-clad politician, I tried to tell the big cat’s story. ‘The Leopard will die if you take it to a zoo,’ I told him. ‘In fact, it will die a thousand deaths.’

‘Death? Who is talking about death?’ he replied equably, looking at me like I was a bit mad. ‘We are soft people. We will take a soft approach. We will give it an enclosure in a zoo. It will live there.’

I paused, wondering where to begin.

‘It will have food and lodging—usko khaane ke liye bhatakna nahi padega (It won’t have to look around for food),’ the minister’s aide added, finishing his boss’s thought.

They were describing the zoo as one would describe a hotel with a free and endless supply of food. Except that leopards don’t want these anthropogenic niceties. The Sohna Leopard returned to my mind, in bloody technicolour against the whiteness of the room.

‘If you put a wild leopard in a cage, it will smash its head against the bars and injure itself. They don’t take kindly to being caught,’ I told him. ‘And a wild leopard can never adapt to a life in captivity. It’s cruel to put it in a cage.’

I suggested a plan for avoidance behaviour for the villagers, chain-link fencing for portions of the village, connecting the park to more wildernesses near Yamuna Khadar so the Leopard could have a larger area to move in, and monitoring the animal through a radio-collar.

At the end of the meeting, Hussain agreed to put the leopard-baiting on hold. He said he would call me back for a meeting on Monday to decide the way forward.

The very next day, the Leopard was caught. It was then taken to a location that was never officially disclosed. The newspapers said it had been taken to the ‘Shivaliks near Saharanpur’.

The move was illegal. The Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972, clearly states that a wild animal can only be captured if it has been proven to be a danger to human life. The Leopard had not attacked anyone. In fact, it had not even been caught from someone’s bedroom; it was in a designated green belt, a place designed to brim over with biodiversity. Each month in India, the forest department tries to catch leopards which go to places we think they shouldn’t—from schools (in Bangalore’s Whitefield in 2016), villages (Malady village in Kerala in 2018), and so on. But in this case, the Leopard was in a park meant for wildlife, and it was eating wild animals. The problem was altruistic: it was as if the cat needed to be punished for existing.

What was unfurling was also wrong procedure: The Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972, says orders to catch or kill animals should be given by the chief wildlife warden. The Leopard is in Schedule I of the Wild Life (Protection) Act. On the issue of hunting or capturing a Schedule I animal, the Act says in Chapter III, Section 11 (a):

(a) the Chief Wild Life Warden may, if he is satisfied that any wild animal specified in Schedule I has become dangerous to human life or is so disabled or diseased as to be beyond recovery, by Order in writing and stating the reasons therefore, permit any person to hunt such animal or cause such animal to be hunted; [Provided that no wild animal shall be ordered to be killed unless the Chief Wild Life Warden is satisfied that such animal cannot be captured, tranquilised or translocated: Provided further that no such captured animal shall be kept in captivity unless the Chief Wild Life Warden is satisfied that such animal cannot be rehabilitated in the wild and the reasons for the same are recorded in writing.

The fact that a minister, not an authorized forest official, was making these announcements, laid bare what leopards face all over India: decisions that are political, not ecological, and judgements that see leopards as pests, not subjects or living beings with importance in their own right.

When you go to a bathroom, you might occasionally find a reason to scream your guts out. That reason is a small insect that looks like it is wearing a brown set of coat-tails—a cockroach. You scream when you see it because you don’t expect the animal to be there. Just then, size becomes a relative term. A small cockroach can become a huge thing. You scream as it flies, as it crawls, as it stumbles in its haste to get away from you, you scream at its very existence. You may not be prone to violence generally, but you throw a slipper on that cockroach, squashing it to a pulp. Or you take insecticide and spray, spray, spray until the little creature is completely and satisfyingly dead. And because you feel it will return even after its death, you squish and spray some more—this time in all the nooks and corners of the house. This is the very definition of a pest: something you don’t expect in the place you find it in, something you want to get rid of because it unnerves you, which you do by behaving in uncharacteristic ways.

Let’s return to the leopard. In its ‘place’—which for many people is a zoo, a protected area or a tiger reserve—a leopard is perfectly beautiful, poised, thrilling, an elegy to muscular prowess. It deserves to be in photographs with carved frames. Outside these places, it requires immediate removal.

A leopard is a pest, quite like a cockroach.

For tigers, the other pan-India big cat, India has a special bond. Even those who have never seen tigers, profess love for them. When Indians feel injustice is being done to tigers, they will light candles, draw slogans, organize protest marches, and knock on the doors of courts. This often involves the coming together of disparate, dispirited groups, many of whom have nothing to do with professional conservation: a union for the striped non-human. No such luck for the leopard.

But the leopard too is beautiful. The leopard too is a big cat. It upholds the essence of wilderness and raises essential questions of coexistence between people and animals. So why are there no protests for saving the lives of leopards?

***