The elephant has been an integral part of Indian culture, history and religious beliefs since time immemorial. From ancient times till the recent past, elephants have played a significant role in the lives of humans, as a vehicle of war and to bear weights or work in plantations. It is no wonder that the elephant has entered the Hindu pantheon in the form of Lord Ganesha, who is arguably the most popular deity in India. The elephant also figures prominently in other religions that originated in India i.e. Buddhism and Jainism.

Ancient Sanskrit literature is a rich source of information on the methods for the capture and care of elephants. The sage Palakapya, who lived in the 5th century in what is now Odisha, is considered the founder of elephant lore as recorded in the Sanskrit classic, the Gaja Shastra. The Ramayana also has references to elephant capture, vividly described by Valmiki. Scenes of elephant capture have been depicted on the walls of the Konark Temple in Odisha. In addition to the records in Sanskrit literature, both the Chola Kings of Tanjore and the Ahoms of Assam have left behind a large collection of elephant literature.

Western writers and commentators on India have also left their own written accounts. They include Megasthenes in 200 BC, Strabo in 130 AD and Indicopleustes in 600 AD. The later European conquerors of India, the British, soon realised the importance of elephants in India and took over the business of elephant capture. They left detailed records on the methods used and attempted to standardise procedures for their capture, training and handling in captivity.

Sanskrit literature lists five methods of capturing wild elephants, one of which was the Khedda method – capturing wild elephants and trapping them in pens or stockades. The word Khedda is derived from the Hindi word khedna which in turn is derived from the Sanskrit khet which means to drive. In this method, wild elephants were literally driven into a pen or stockade by skilled mahouts riding domesticated elephants. Over time, each of these methods came to be associated with certain areas of the country. The Khedda method, associated with the eastern part of the country, was later introduced with various modifications to other parts of the country as well, the most famous of which was the Mysore State. Some of the most successful Khedda operations were staged in the Kakanakote State Forest, now part of the Kabini area of Nagarahole National Park.

The first person in the Mysore State to try and capture elephants in this manner was Hyder Ali, the father of Tipu Sultan, in the 17th century. He was unsuccessful and no further attempts were made for a while. The British were the next to try and an attempt by Col. Pearson, a British Army officer, in 1867 also resulted in failure.

The next attempt was from another British officer, this time from the Canal or Irrigation Department, named G.P.Sanderson. He had no previous experience in capturing elephants but was interested and knowledgeable in the behaviour of wild elephants. He put forth many proposals to the Mysore Government for the capture of wild elephants and in 1873 the Mysore Government accepted his proposal and placed him in charge of all elephant capture operations in the state.

He was successful in his second attempt in 1874 at a place called Kardihalli. In 1875, he was put in charge of the British Elephant Catching establishment at Dhaka for a period of nine months. On his return from Dhaka, he adapted and perfected the Khedda system in Mysore. He is said to have brought experienced mahouts from Dhaka who formed the mainstay of the operation. In time, the Kuruba tribes of Mysore and others learnt the art of elephant-driving. After that, Khedda became a regular feature in Mysore State. A total of 36 Kheddas were conducted in Mysore till the last one in 1970–71.

The Kakanakote forest, now the D.B.Kuppe Wildlife Range of Nagarahole National Park, became a favoured staging ground for the Khedda and as many as 24 were staged there. The Kakanakote forest comprised of tropical deciduous forest with a good amount of bamboo. They extended over large tracts, and along with the Begur forest, now part of the Bandipur National Park, on the opposite bank of the Kabini River, they were home to vast herds of wild elephants.

The Mysore Kheddas, especially the ones at Kakanakote were different from the Assam Khedda. The Mysore Kheddas were massive undertakings that required a large number of men and kumkis (tame elephants trained for capturing wild elephants). Wild elephant herds had to be driven in from long distances and were moved in stages and held when necessary in position until the exact time when they would be driven into the stockade in full view of distinguished guests.

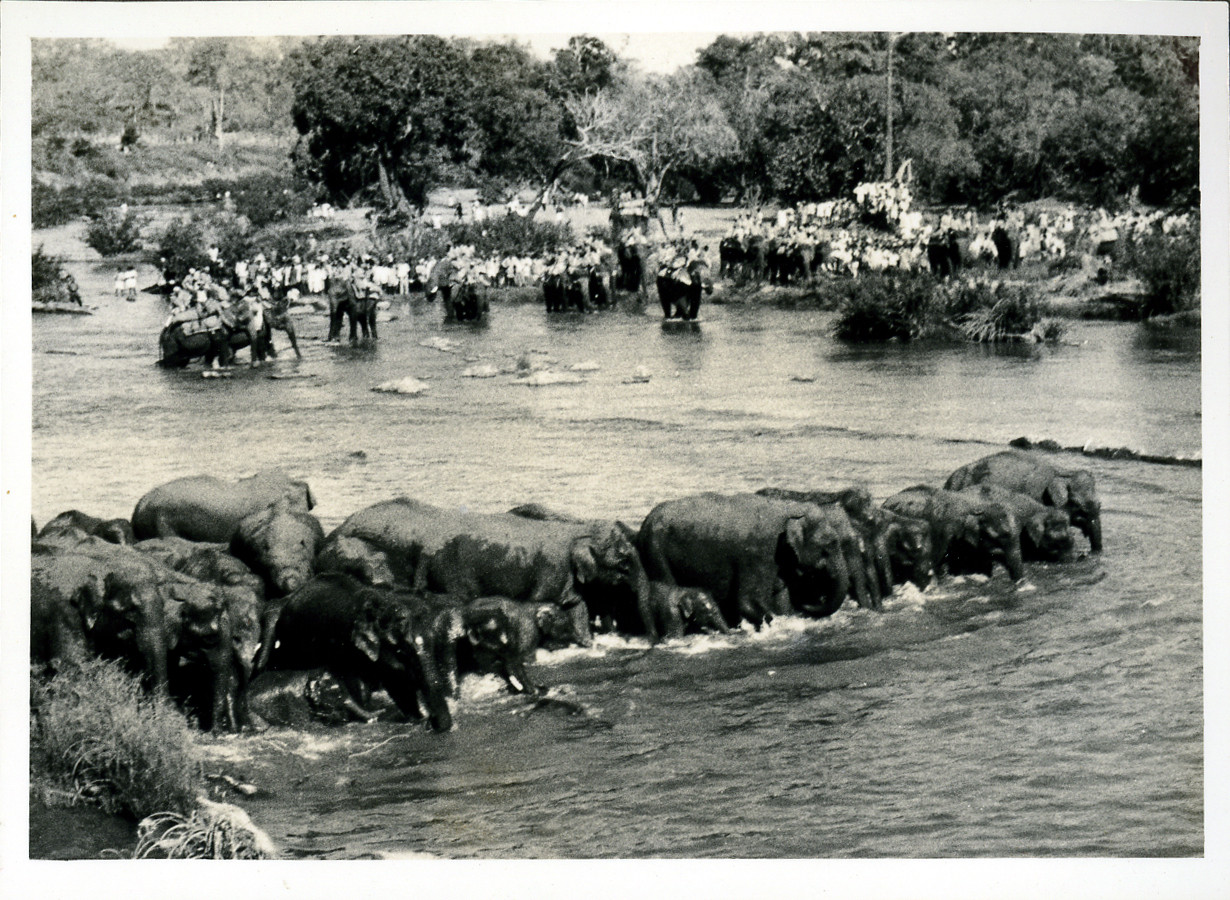

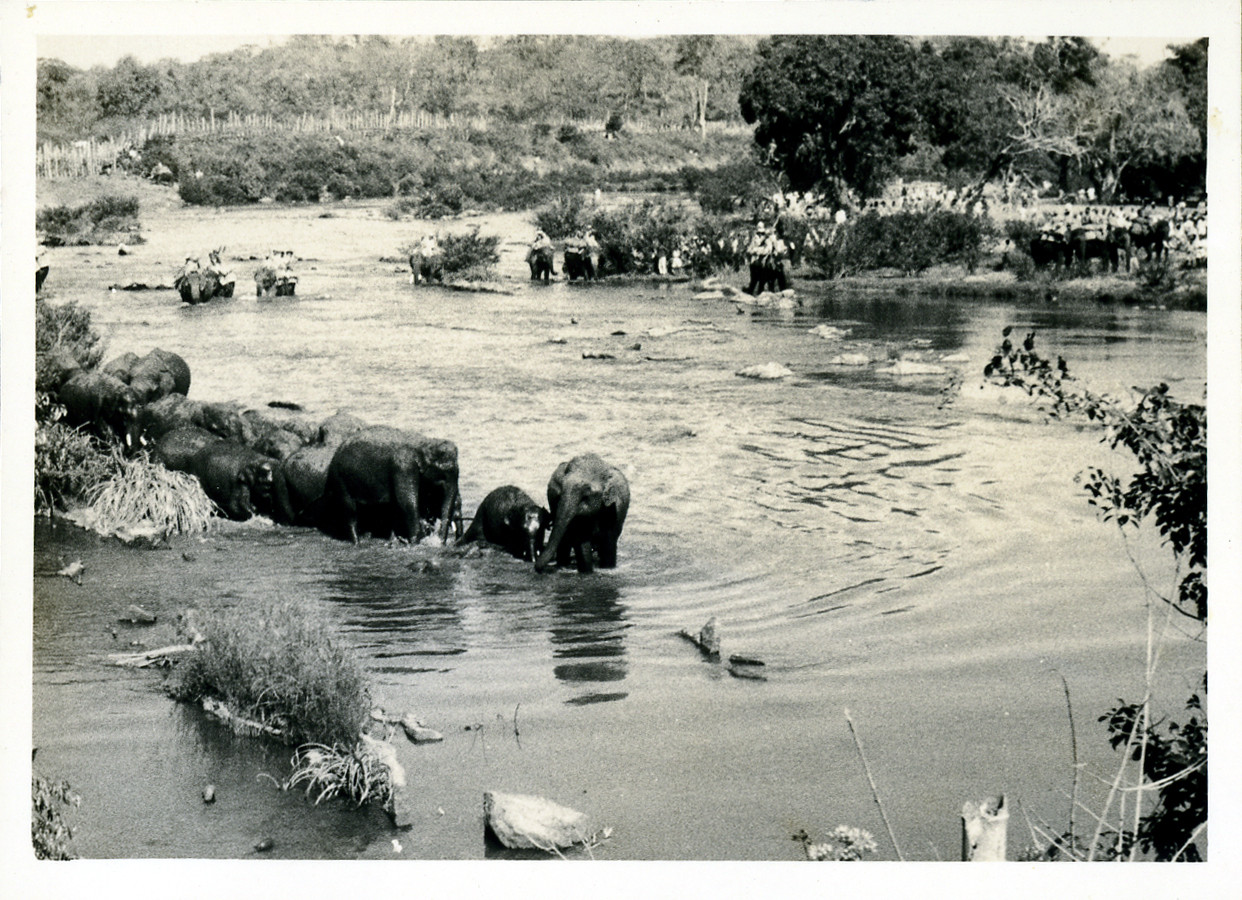

This involved months of planning and preparation; as many as forty kumkis and a thousand men would be used. The size of the stockade would extend over five acres. The unique feature of a Kakanakote Khedda was the river drive which was first designed and carried out by G.P.Sanderson in honour of The Grand Duke of Russia during his visit to Mysore in 1891. In the river drive, the elephants were driven across the Kabini river into the stockade and this proved to be a popular spectacle with a special visitor’s gallery being set up to allow people to witness the grand finale.

The only other elephant capture operation that could compare with the Mysore Kheddas as a spectacle were those of Thailand. Here too the Khedda method was of ancient origin and was staged every few years near the city of Ayutthaya. It is interesting to note that the Kraal method of capturing elephants as practised in Sri Lanka is comparable to that of Mysore and Thailand.

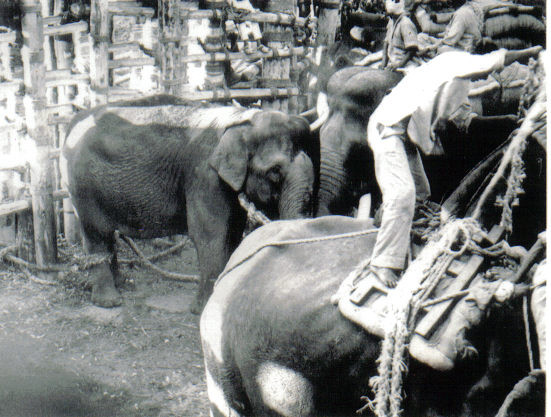

Another aspect of the Khedda was the roping operation, which involved moving the captured elephants out of the stockade and choosing individuals that were deemed suitable for training. Kumkis bearing their mahout and one additional person would enter the stockade. Paradoxically, the movement of these kumkis among the captured and now very nervous and suspicious herd would have a calming effect on them. Once the herd had got used to the kumkis and calmed down a bit, the mahouts would slowly and gradually start separating individual animals from the herd.

Two or more kumkis would ‘sandwich’ the separated individual and the additional person seated behind the mahout would descend to the ground with ropes and hit the wild elephant’s hind leg. This would make the elephant lift its foot off the ground and the person would slip a rope around it. The other end of the rope would be fastened to the kumki. Both hind legs would be bound and a third rope would be slipped over the captive’s neck. Gradually, in stages, the captive would be led out of the stockade and fastened to a tree at an elephant camp specially established for this purpose.

One by one all the elephants would be separated and fastened with the exception of calves that were still nursing and would be permitted to stay with their mothers. The roping operation was one of the most dangerous of all tasks associated with the Khedda, especially when females were separated from calves that were already weaned. I don’t have to describe the trauma and frenzy that would have ensued when this was done.

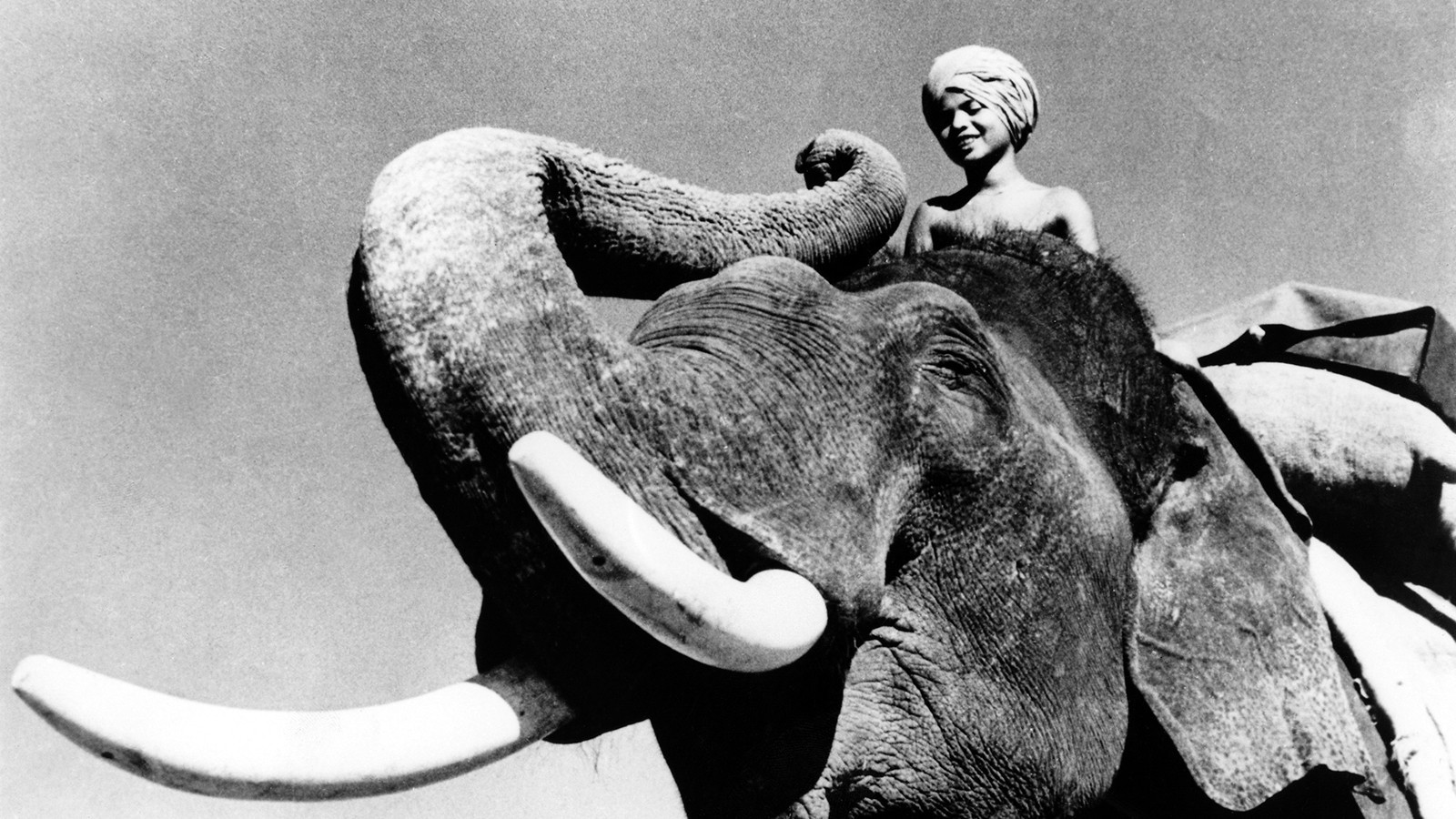

The Mysore Kheddas also threw up the first Indian star in Hollywood. In 1935, Robert Flaherty arrived in Mysore to make a film called Elephant Boy, produced by Sir Alexander Korda. It was based on a story by Rudyard Kipling called Toomai of the Elephants from his bestseller, Jungle Book. The role of Toomai was played by a boy called Sabu Dastagir, who was born in Karapura village on the banks of the Kabini where there was a large elephant camp. The Kabini area was the hunting ground of the Maharaja of Mysore and a royal hunting lodge was situated there. Sabu was the son of a mahout and was raised among the elephants in the camp. His mother died early and legend has it that a female elephant rocked his cradle. His father died soon after and he was subsequently raised by the Mysore State.

The movie was shot in the forests along the banks of the Kabini and included a Khedda, which was specially staged for the movie shoot. After shooting on location, Sabu accompanied the unit to London to complete the film at Korda’s studio. Sabu eventually moved to hollywood where he starred in various movies such as The Jungle Book, The Drum and The Thief of Baghdad. He returned to Mysore for a visit in 1952 and was seen driving a Cadillac.

At the age of 39, in 1963, Sabu Dastagir died of a heart attack in his home in Chatsworth, California. He was survived by his wife, the former actress Marilyn Cooper, his son, Paul (singer, songwriter, producer, and guitarist) and his daughter, Jasmine. His funeral service was conducted at the Chapel of the Hills, Forest Lawn Memorial-Park Hollywood Hills. He was last seen in the Warner Bros. film, Rampage.

Fortunately, Khedda operations are now a thing of the past and the last one was conducted in 1970-71 just before the construction of the Kabini dam. Where wild herds were once driven out of the forests into captivity, the backwaters of Kabini is now one of the few remaining safe refuges of the Asian Elephant.

First published on the author's blog.