The very first time I saw an octopus, it was in the hands of a boatman who had chanced upon it in a shallow reef off Havelock, in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and poked a stake through it to claim it for himself. A few years later, while wandering in the frozen food aisle of a supermarket in Zurich, Switzerland, I spotted octopuses packed in styrofoam and cling wrap; beautiful marine beings lying dead far away in a landlocked country. As someone who has been endlessly fascinated by octopuses all my life, these ‘sightings’ were heartbreaking.

But, since I am yet to get over my irrational fear of deep waters, meeting a wild octopus is only the stuff of dreams – which is why I find solace in meeting them vicariously through nature documentaries. The internet is a treasure trove of video clips of octopuses executing mind-bending camouflage displays. “Octopuses can change what they look like in less than 30 milliseconds!” screams one video. “The Giant Pacific Octopus has three hearts, nine brains and blue blood!” says another. My search for the best octopus film sequence continued in this manner till I watched one of the most extraordinary wildlife films, ever. It starred an octopus in the leading role.

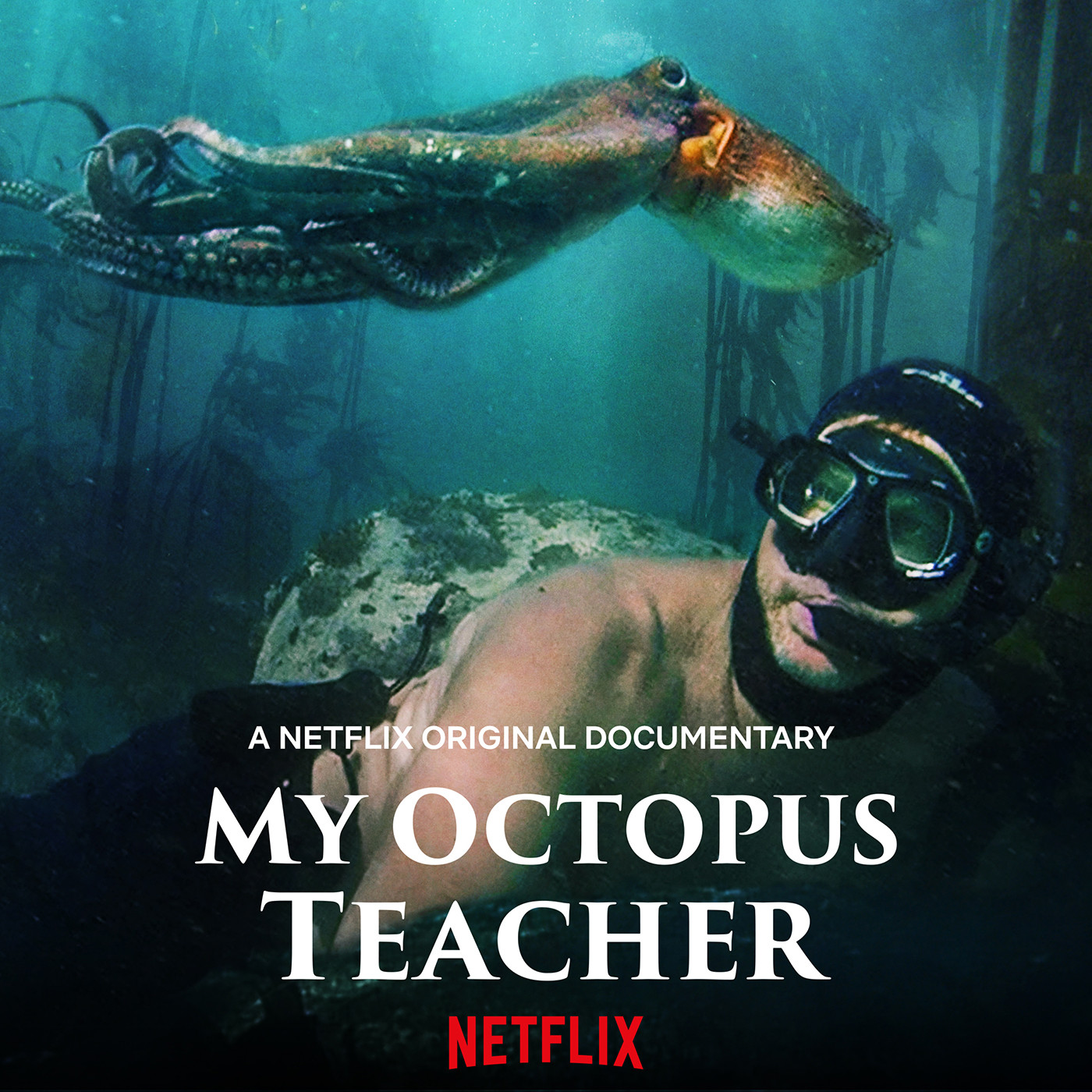

My Octopus Teacher narrates the story of Craig Foster, a natural history filmmaker from South Africa, who decides to dive every single day in the Great African Sea Forest in an attempt to rekindle his connection with the wilderness and his own self. In those freezing kelp forests, he meets an unusually curious octopus with whom he develops a close emotional bond over the course of a year. The film is an immersive visual and sensory experience, with indulgent views of the verdant underwater world and the star of the film – the intelligent and sentient octopus. As the film unfolds, you will be mesmerised by her, you will crane your neck to spot her before the camera does, you will fear for her safety when a shark shows up, you will cheer for her as she hunts a crab and you will fall in love with her. Needless to say, you will cry for her.

Now streaming on Netflix, My Octopus Teacher has won hearts like no other wildlife film has. Most recently, the film was the star of the show at the 2020 Jackson Wild Media Awards, clinching over nine awards including the Grand Teton Award. The film is a collaboration between the Sea Change Project, Off the Fence Productions based in the Netherlands and Netflix. Over email, I spoke to Craig Foster, the producer of the film, and Pippa Ehrlich, who co-directed the film with James Reed. She also filmed along with Roger Horrocks and edited the film.

Thank you, Swati, for facilitating the interviews.

Craig Foster

What are your memories of your earliest dives? Did you dive in kelp forests back then too?

I dived in kelp forests back then too. As a child, it was just a wonderful, adventurous landscape: the fish, the crabs and the lobsters were all very exciting. The tidal pools were also of great interest; the shells and bits of other sea-shaped things were like treasures.

To you, does the outside world pale in comparison to the underwater world, from a visual and sensorial point of view?

In every way, the underwater world is more compelling than the one made by man, above water. However, I am lucky enough to live where I do. Cape Town is blessed with such natural beauty; the mountains, the Fynbos and the coastline, it is all pretty spectacular. But what I find in the Great African Sea Forest is pure wilderness. There is nothing tamed down there. There is a sensation of being in a three-dimensional space through which you can fly. It is pretty extraordinary. Not to mention that with not very much known about this unique ecosystem, there is so much to discover, study and find.

One of the most incredible moments in the film is one where the octopus plays with a school of fish. During the course of your interactions with her, did you sense many different moods?

In a sense, of course! But it is hard to tell what a cephalopod is thinking. While her neurological makeup has some small resemblance to ours, so perhaps there could be 'emotion' in the way we understand emotion, but it is hard to classify how that is felt in the cephalopod mind. I did observe different behaviours though. Plus she was more curious than a lot of other octopuses, which allowed me to spend all that time with her. Her strategies for hunting, how she learnt and adapted, her various 'moods' which were the various colours and textures her skin would take and change into, and the shapes and postures she would adopt to move or hide, all of it was fascinating. Of course, that moment with the fish was so unique and different, that to me felt like she was playing. It is not a huge stretch to think so because when animals are naturally curious and intelligent in their design, it seems like 'play' would be something they would do. It has been studied and observed in captive octopuses but never in wild ones, so it is an observation more than a scientific fact.

What were the challenges of pulling off a coherent narrative after all these years? Could you give us a sneak peek into the notes you recorded from your dives back in 2010?

Pulling together the story was a daunting task. My observations were pretty much the hundreds of thousands of images and videos, and also my study records from what I had observed in the sea forest. I had a mental map of the place underwater, that is in the book Sea Change, and I had thousands of photos tacked on a board to record the progression of things I had observed of new species, of behaviours and not just of the octopus. I wrote personal notes on certain experiences to record my observations. So it was an absolute melange of everything that had to be sifted through to tell the story. I made a promise to dive every day from 2010, which I have done. It was a few years into that process of getting accustomed to the cold and the ecosystem that I met the octopus.

What is your vision for the Sea Change Project? Since the release of the film, have you seen increased interest locally in the protection of these unique kelp forests?

The response to the film has been overwhelming. We get a mail or message literally every five seconds from around the world. Locally too it seems to be making people aware of this extraordinary ecosystem at their doorstep. When I co-founded Sea Change Project with my friend Ross Frylinck, who also co-authored the book Sea Change with me, we just wanted to create an organisation of like-minded people who spent every day in deep nature immersion and told stories of the joy and the wonder, to create interest and raise awareness about the Great African Sea Forest. We want to make it a global icon and create an interest in its long-term protection.

Two hours every day for a whole year, that's a lot of time spent with one animal. Looking back, is there any specific moment that you treasure the most?

Looking back now, I treasure every moment because what she allowed and gave me I know is a once in a lifetime privilege – a glimpse into the heart of the wild. It changed my life. Of course, every time she displayed new behaviour or I learnt something new about the environment thanks to her, it was always special. And the occasional contact she would make of her own volition was so wonderful. But just to be in the presence of a wild animal for so long in such a consistent manner was magnificent.

How did having such an intense emotional relationship with a sentient animal change you as a person?

I hope it has made me a better person! It certainly helped pull me out of the burnout and depression I felt initially, which had me going into the water in the first place. It sensitises you to the wonder of sentience in the world around you, the understanding of how precious wild places and wild animals are. And, how much a part of that wild we are, that living with a disconnect to nature is very harmful to the human psyche.

And finally, how does it feel to be hugged by an octopus?

Indescribable. It is always lovely to be hugged by any animal, by your cats and dogs, for instance. But when it is a wild animal, and she approaches you of her own volition, it is magic! Also, one can’t tell what is going through her mind. It is just a moment of recognition, one non-human animal to another human-animal, recognising that it is the animal in their common makeup that is binding. It is a tremendous trust from the wild, and it is beautiful.

Pippa Ehrlich

You had the daunting task of going through notes and footage spanning many years to come up with a storyline. How and where did you begin?

It was a very daunting task. We started with an outline Craig had written and then spent months and months going through his enormous library of footage, debating multiple story beats. At first, we thought the film might cover a much broader range of content, but the deeper we went into the story of the octopus, the more we realised that this would be the core of the narrative. Once we started editing, the story of Craig’s experience with the octopus just started telling itself.

Craig mentions in the narrative that the sea is dangerously stormy in these parts. How challenging was it to plan your shoots and sound recording sessions here? Did you have days when you couldn’t get anything done on the field?

Craig is in the water every day and has been for many many years now. So he knows exactly how to judge conditions, and much of the film had been shot long before I became a part of the project. There are very few days when conditions are perfect, so when those days came around we worked especially hard and spent long hours in the water. As Craig mentions in the film, there is a protected place in the kelp forest, where he met the octopus, where you can film even in quite rough conditions. We had some interesting experiences shooting on stormy days and on one of those drone shoots, Craig lost a fin and had to swim really hard to get back to the shore.

Are there any memorable interactions with underwater animals that you experienced during your dives in the kelp forest?

I have had very many profound experiences with animals in the kelp forest. On my very first dive with Craig, a tiny shark only a few days old swam into my hands. I’ve been approached by otters in the water and had them swim around me for ages, even reaching out and touching my fins. We’ve also had dives with whales and seals. Having meaningful encounters with these big, charismatic creatures is mind-blowing. But often, it is watching tiny things, like sea slaters swarming up the beach or starfishes chasing urchins, that teaches you the most and gives you the deepest insights into nature.

While writing the script for the film, did you have to be overtly aware of how anthropomorphic the narrative should be? Especially with sharks, because the audience is going to fall in love with the octopus, and by extension, dislike her natural predators.

This film is not scripted, it is all based on the interview with Craig, but certainly, we sculpted the story. We were aware of avoiding anthropomorphism, which is why Craig did not name the octopus. We also flew Professor Jennifer Mather, a top octopus scientist and psychologist, out from Canada to review the film and give us insight into the octopus’ behaviour to ensure that we were explaining things as accurately as we could. Of course, it is impossible to avoid anthropomorphism entirely, especially with a story like this, and the shark/octopus narrative was especially tricky. In earlier versions of the cut we included a more in-depth shark narrative, but it became a distraction from the octopus, which is why we included the shark hatching in the final sequence. Every animal is just as important and miraculous as the next, and I would hate to think that our film has created any anti-shark sentiments. Pyjama Sharks are my favourite kelp forest creatures.

How was the process of collaborating with James Reed in working out the final storyline? Since he joined the project much later, did the outsider perspective help in shaping the structure of the film?

Having an objective perspective was absolutely critical for making this film what it is. By the time James came on board, Craig and I had been neck-deep in the sea forest and the edit for years. I had tried to interview Craig several times, but because we already knew each other so well, it just didn’t seem to work. The interview you see in the film was run by James, over three days. I was in the room shooting the second camera, and it was one of the most intense storytelling processes I have ever witnessed. James is a world-class interviewer, and there is something deeply authentic that comes out when a subject is telling his story to someone who has never heard it before.