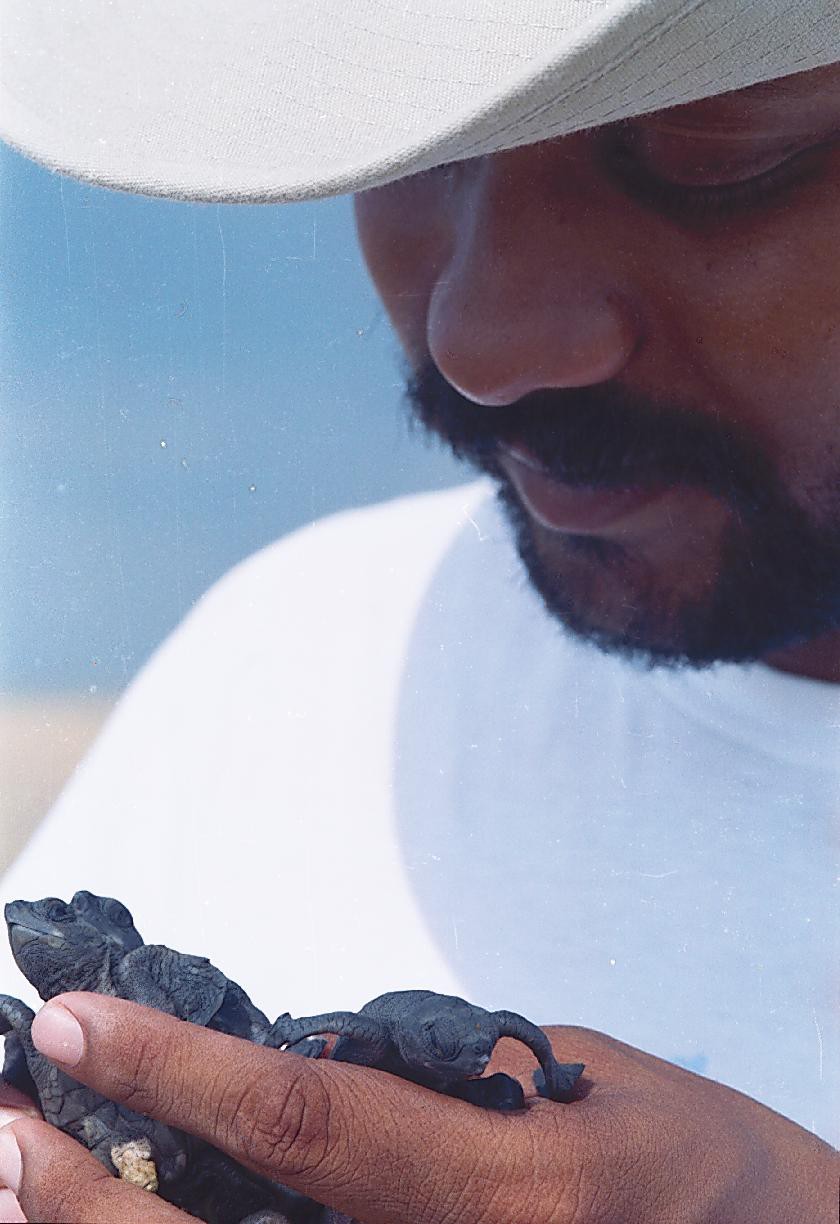

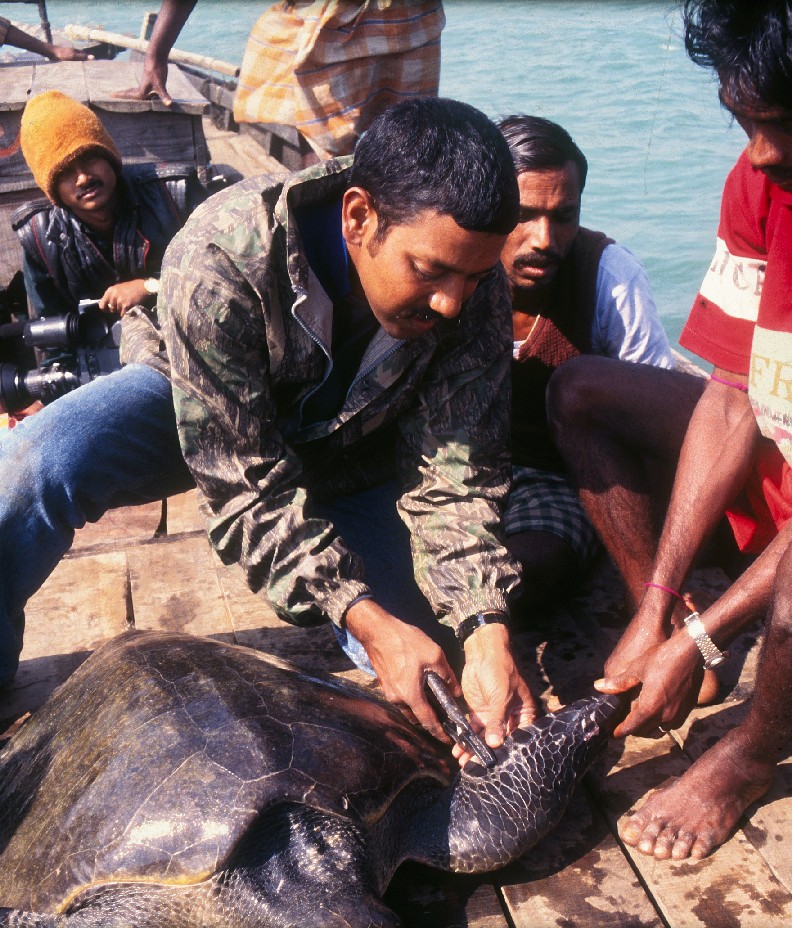

Bivash Pandav is a biologist who has been associated with the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), Dehradun since 1991. Throughout his career, he has focused primarily on two very disparate species – tigers, and Olive Ridley turtles. Pandav has spent close to a decade on the coast of Odisha, and has tagged nearly 20,000 Olive Ridleys as part of his research. While coordinating WWF-International’s tiger program, Pandav has travelled extensively across Asia’s tiger habitats. In India, he has studied tigers across the Terai landscape, and has helmed long-term programmes to monitor both tiger and prey populations in Rajaji Tiger Reserve, Uttarakhand.

We get to know him a little better.

You have said that conservation cannot be a top-down process, and has to involve the local community. You’ve worked with village settlements near tiger reserves, and with fishing communities in Odisha. How do conservationists ensure that they work with local people and not against them?

We are not being honest with our commitment to local communities. We talk about nature tourism benefitting the local community but it really benefits the hotel industry. Rich men get the maximum returns from tiger reserves. Aside from a few exceptions, local people hardly control tourism activities in their region. Maybe they’re washing the linen or something, but they aren’t running the hotels. Unless earnings from protected areas go directly to local people, antagonism is bound to happen. In Hemis National Park Ladakh, and in Nepal, there are some models in place that are working. The local people have more of a stake in safeguarding the area than any of us living in cities, so they are the ones who need to see direct benefits. In order to realise long-term conservation targets, administrators must preempt discord that is likely to arise between the forest department/conservationists and human communities whose livelihoods are affected by the protections. Conflict between humans and wildlife is bound to happen and is happening!

For a healthy tiger population, healthy prey populations are essential. Could you talk a little about what affects prey population, and what your research on monitoring prey populations in the Indian context has uncovered?

A healthy prey base is one of the biggest factors for a healthy carnivore population. Where there is low density of ungulates, like in the Sunderbans or Silent Valley, there is a low density of tigers. In the terai region, and the alluvial plains, like in Corbett, there’s a higher density of prey, and therefore tigers. Sambar makes the best prey – it has a large body, it is solitary, nocturnal, meek, and is an animal of dense forest; there are others like gaur and wild water buffalo of course, but they are more aggressive. That is why sambar conservation is tiger conservation. We need to protect our large prey. Instances of sambar poaching need to be viewed as seriously as tiger poaching, it should not be taken lightly.

A lot depends on human behaviour. Large parts of the country like the northeast, and parts of Jharkhand, Chattisgarh, and Odisha, are almost devoid of prey. There is very little food available for tigers because people have eaten all these animals up. But in areas like UP and Uttarakhand, where there’s a larger percentage of vegetarians, there are more tigers. Widespread vegetarianism is really one reason why India still has a large population of tigers. I’ve worked in 11 tiger range countries – in Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, most of the prey has been eaten up. Only in the central spine of Malaysia and Sumatra, some tigers still survive because wild pigs are taboo for communities there, and are therefore available as prey.

The quality of the forest also matters, of course – habitat management is a big issue. When it is degraded, unpalatable species like Lantana proliferates, which has a massive impact. We need more active management to eradicate this.

Many conservationists talk about the importance of coexistence between humans and wildlife, but you hold a different point of view. Could you explain?

What I have been studying for around 14 years is how the creation of inviolate space helps in reviving prey populations and habitats, and in turn, tiger populations. If you have to save tigers, you cannot be talking about coexistence and shared spaces, it has to be inviolate. Tigers may co-occur with people, but they do not coexist. Our studies give a clear indication that pastoral communities with good packages will move out. In Rajaji and Corbett Tiger Reserves, the government has relocated 2000 families and as a result, there has been a tremendous recovery of tigers. I have been monitoring it and I am absolutely convinced.

Our research shows that where there is grazing, or lopping of trees, wildlife is deterred from that area, and it also becomes difficult for the forest to regenerate – as the canopy opens up, the forest floor becomes dry and degraded, and this encourages the growth of unpalatable species. We have this utopian idea that all communities are living in a sustainable, harmonious way with the forest, but it isn’t true.

You’ve emphasised many times that Olive Ridley nesting beaches have to be protected if we are to conserve these sea turtles. But what do you say to those who argue that this view tends to be anti-development or hindering progress?

Rapid development and urbanisation along the coast is really affecting the nesting beaches, and on the other side, there are the mechanised fishing operations causing turtle mortality. There is 480km of coastline in Odisha, and mass nesting takes place in a total of 6km. Can’t we separate 6 out of 480? It’s not even 1/50th of the coastline we want safeguarded, so it is not fair to say conservationists are against development, or ports, or national security, etc. There are clearcut solutions, and they need to be implemented. For instance, there is no policy as far as lights are concerned, which we know disorients turtles on their way back to the water. We can easily have turtle-friendly lighting of low-intensity wavelengths along that part of the coastline.

Every year, tens of thousands of Olive Ridleys die during their breeding and nesting season in Odisha. Why have turtle-excluder devices (TEDs) not been as effective as we hoped?

We have encouraged the use of turtle-excluder devices (TEDs) through the breeding season. But a TED is a gear-specific device. It can only be used in a trawl net, but it’s not possible to use it in gill nets, shore seine nets, or with hook and line mechanisms. In that region, I think there are fewer trawlers than gill nets. The other issue is that some of the other catch also escapes through this TED escape route – and because trawl operators don’t want to lose any of their catch, they don’t use the TED.

Enforcement is very poor in the sea – once in a while when the coast guard or another enforcement agency does ask about it, the trawler boats all show them the TED they carry on board, but to the best of my knowledge I have not seen any trawl net actually fitted with it. That is why prevention is a better approach. Actual enforcement of the ban on near-shore mechanised fishing activities is needed – just 5km would be enough, as Ridleys mate close to the shore, not in the deep sea. If this area is effectively patrolled, just from November to February, mortality can be minimised along reproductive patches. It would also protect the rights of traditional fisherfolk in the region. This is one of the easiest solutions that needs strict implementation.

Bivash Pandav showcased his work at the Nature inFocus Festival, 2017. If you missed it, or would like to listen to his talk, here it is.