Julian Matthews is the founder of TOFTigers, an organisation started in 2004 in response to the plummeting tiger numbers across Asia. His expertise and experience in nature tourism has been the driving force behind the organisation's efforts to improve the ecological and economic sustainability of wildlands and wildlife of southern Asia. It is something he refers to as 'Tigernomics', the power of the world's most loved animal to turn around its own future and that of a myriad of other species and a billion humans that depend on these natural habitats that these wild cats call home.

We talk to Julian about his journey into conservation and the crucial role of tourism in the future of India's wildlife and wild spaces.

From Discovery Initiatives to TOFTigers. Could you talk to us about the journey and the inspiration behind the same?

I was born and brought up on a game and cattle farm in Africa. As a young man, I had decided to work in the UK with my father-in-law, Colonel John Blashford-Snell, a well known explorer and conservationist who had run a very successful organisation taking young people into the wild all around the world. After what was a wonderful introduction to this field, I started my own specialist travel company called Discovery Initiatives (later known as Steppes Travel) which I ran for 15 years. Our mission was to use safari tourism as a conservation tool – to use our business to help fund protection, wildlife research and community integration in conservation. We worked with all the big conservation agencies and had the opportunity to work with some very special people and their organisations: Jane Goodall on Chimpanzees, Birutė Galdikas and the Orangutan Foundation, Iain Douglas-Hamilton on African Elephants and a host of other researchers and scientists.

As for how TOFTigers happened, I saw my first tiger in Nepal, in the forests of the Bardia National Park. About 3-4 years later, in the late 1990s, I went to Ranthambore, and I was very upset – that would be the right word – about how they were implementing tourism here. It was very much a safari park approach to game-viewing – rush in and out, drive around in circles at great speed trying to find things. It wasn't a great wildlife experience. I was used to expert naturalists in Africa and around the world, showing you nature at a slow pace with great insight, and that wasn't happening here. What happened two or three years later was the announcement that India was losing its tigers. In 2003-04, tigers went extinct in Sariska and Ranthambore was down to just 11 individual tigers in its entire landscape.

What has happened in Africa and other parts of the world was a much cleverer way of applying the economics of visitors, a much more integrated approach to their experiences , and the money being made from tourism was being more effectively used to help stop poaching, to help integrate communities and fund protection. I set up this organisation called TOFTigers (Travel Operators For Tigers as it was originally called) to apply international pressure to affect better practices and policies, to put in legislation to allow tourism to be more effective, to ensure that the economics of tourism were being beneficial to local communities, and to build better experiences for tourists visiting India's wilderness.

Is nature and wildlife tourism still a foreign concept in India, and what are you doing to try and change that?

Even though economically tourism is an important part of the forest department's responsibilities and they recognise this explicitly now, India still lags behind – given its extraordinary biodiversity and is still not much further down the line as it could be. Currently, tourism in India's national parks is at about six million visitors a year. In the national parks of America, they are taking in about 60-70 million people and are generating about $800 billion per annum in revenue for the conservation of wildlife. India is tiny tiny tiny by comparison. At the same time, India's tourism is going to grow exponentially in the next 30 years and should be now planning for it much more comprehensively to ensure sustainability.

What we attempted to do and continue to do is to encourage sustainable tourism and to highlight it as an important aspect of protecting nature and wilderness. Tourism is important as a generator of funds for protection and tax for the government, as a way of generating jobs and livelihoods for local communities, and as a way for allowing its citizens to enjoy and understand why they need to save these habitats. Bizarrely, this still has to be reminded to the forest department, because they have never been trained in tourism, they don't like dealing with the accountability and the hassle that this tourism has brought with it.

Now with the research that TOFTigers and others have done, it is proven that nature based tourism is a good thing for parks, visitors and communities. Wherever there is a good tourism economy today, there are good and often increasing tiger numbers. Where this is not happening, tigers and their landscapes are in big trouble, like some Northeast states, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha. But then already we have destinations where there is too much poorly-planned tourism happening. We have gone from the position of having no tourism to too much tourism in a decade. Now, we need to make sure that India has a vision and a roadmap for the next 20 to 30 years and not just tomorrow.

'Sustainable tourism' is a word that is constantly thrown around within the industry. What does it really mean in the Indian context?

The real baseline to ensure sustainable tourism is to have good laws and policies, which India just doesn't yet have in a comprehensive manner. It has lots and lots of environmental laws, but they are mostly contradictory, and none are focused on how to use this new tourism economy more effectively to conserve and protect.

As you probably know, the vast majority of forests in India are owned by the government, and it hasn't as yet been prepared to allow the full integration of neighbouring communities into conservation and wildlife support. It has been a hands-off approach, 'You can't do it, we are the only guardians of wildlife'. That is fundamentally, both in India and around the world, incomprehensible and unworkable. Governments shouldn't be the only guardians of wildlife, peoples and communities should be the guardians and should be integral to conservation and protection outputs.

In places in Africa and South America, they have allowed whole communities to take control of the landscape that they live in or next to and to be involved in it, invest in it, conserve it, and to be an active participant and stakeholder in it, with nature tourism being the economic tool behind it. That way, you start getting sustainable tourism, you start getting a relationship between the money earned and where it is going towards, not only protecting a habitat and saving endangered wildlife but ensuring that neighbouring communities are the main beneficiaries.

From the perspective of tourists and travellers who are interested in nature and wildlife, what can they do to bring about a more responsible form of tourism?

Tourists usually just book a place, try to get the cheapest deal they can, and arrive with little knowledge. They need to be more questioning and use their practising power to choose the right providers and thereby demand more sustainability. There are several things that they can do. When they book, do the research, find out the best providers and operators, like those in our wildlife travel guidebook, who commit to best practice. When you go to the lodges and parks, question where your money is going and how it is being used, and ask the forest staff what they do and how they do it. This helps TOFTigers do its job too.

That is what we are trying to do with our PUG & Footprint certification programmes. Everyone in Indian tourism says they are in ‘ecotourism’, but sadly that is simply not true. Most businesses wouldn't even meet the minimum standards of ecotourism. So we had to distinguish the good, the bad from the ugly. It was not something we were particularly interested in doing, as an organisation, but in order to tell visitors how they could best support parks with their visits and ensure long-term sustainability, we had to start to work with the best providers and assure that they get the business that they deserve for the work they are putting into their own landscapes, their local staff, their neighbouring communities and the destinations they serve.

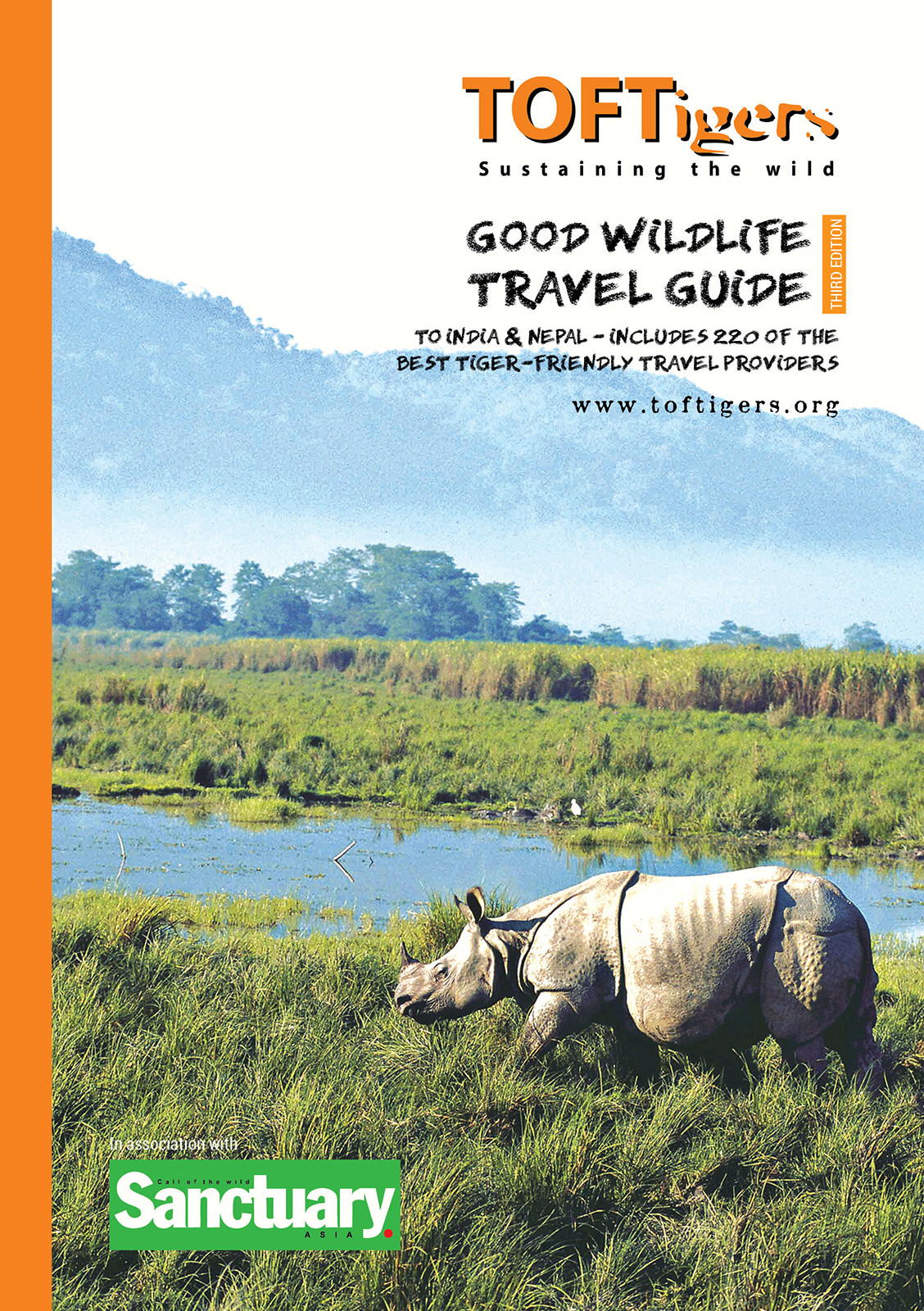

In terms of numbers, we have 70 lodges and resorts in 26 different destinations. We have another 200 companies, both in India and around the world, who have committed to more sustainable operating practices. They are all in our Good Wildlife Travel Guide which is available to download on the site.

What is the way forward for India’s wildlife and tourism?

The great news is that India has saved its tigers. From what I have seen in person, in Ranthambore for instance, there were 11 tigers when I started TOFTigers, and now it has over 70 individuals, which is a 7-fold increase. An extraordinary success story – and there are others not dissimilar across India

.

A lot of this has been done, not only by the forest department’s praiseworthy commitment, but by the economics behind nature tourism and the attention and accountability that this industry brings with it to these once forgotten and undervalued lands For example, Ranthambore and two or three other parks in India are now wholly self-sufficient and could stop depending on both state and federal funding. They now could be run fully on the park gate fees; with funding for protection and conservation and for the local communities bordering the parks. This offers new futures and opportunities for field directors and there is even a noticeable behavioural change in these destinations with benefiting local communities now far more pro-wildlife, and that is very encouraging for the long term.

So Indian conservation does have a good future. It has got a very good record in saving endangered wildlife and restoring wilderness now. It has got all the expertise, the skills, and increasingly the money – and it certainly doesn't need foreigners like me to advise them what to do. Indian travellers and foresters are increasingly moving around the world, seeing how things are being done elsewhere and bringing their experiences back to India. Down the line, India should be looking at all its 760 reserves and sanctuaries, planning to allow tourism to be spread further and thinner across wildlands, as well as creating community conservancies outside of protected areas, thus allowing communities to have some stake holding in the wilderness around them, which Nepal does really well now.