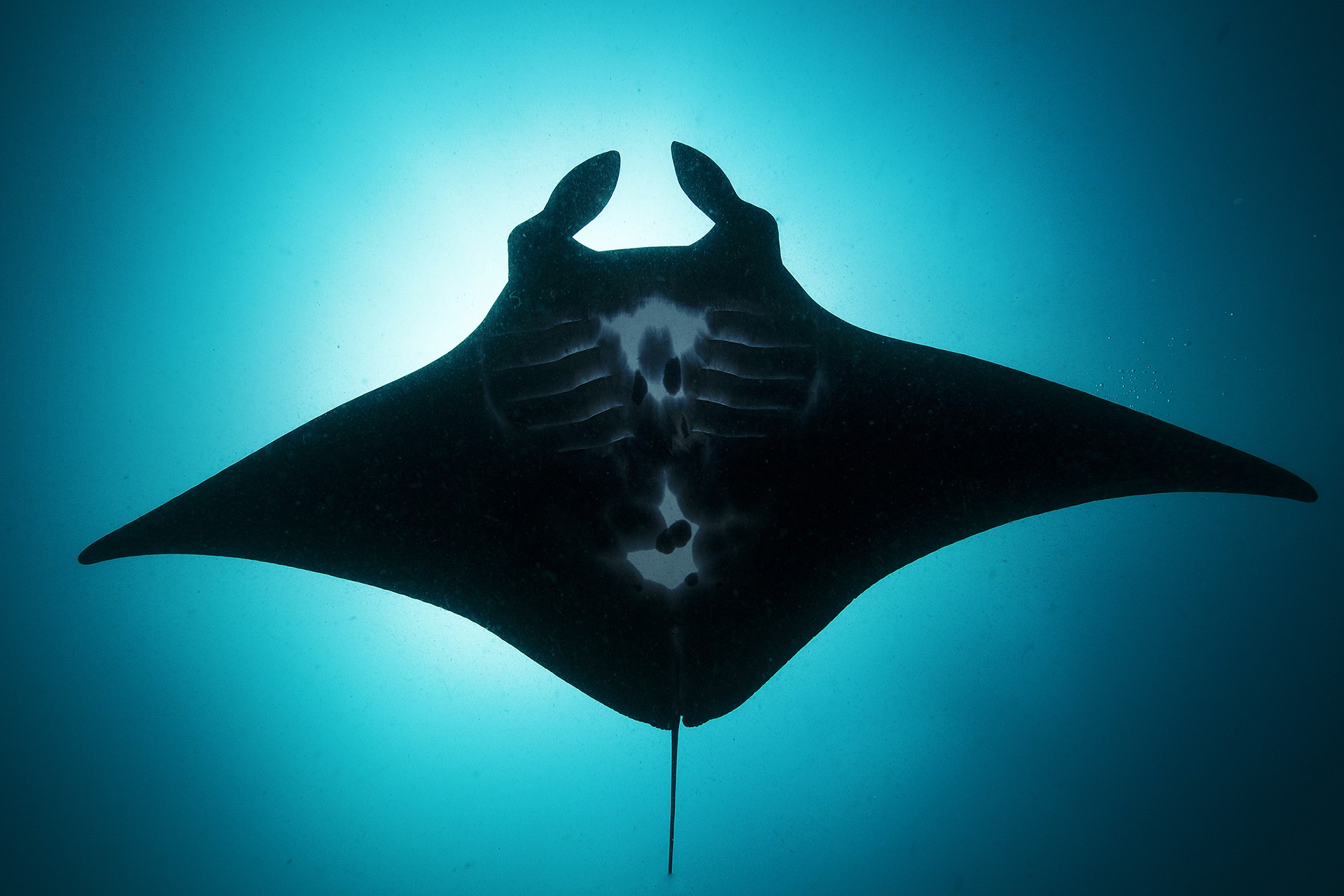

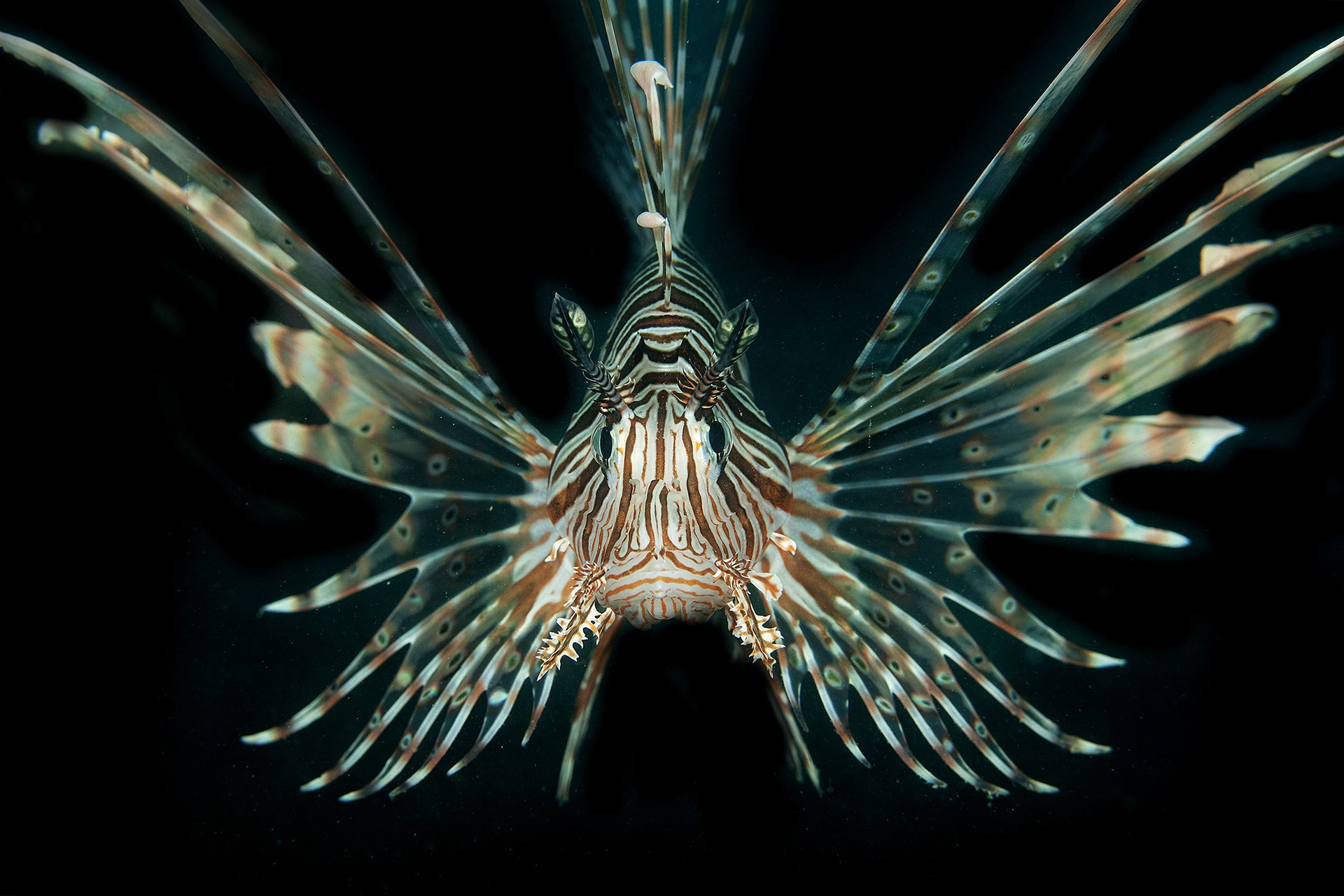

Ask most people about wildlife in India, and they’ll come up with stories about forests, about tigers, leopards, elephants. Yet, this is only a small part of a bigger picture. Remember, the subcontinent has around 7,500km of coastline, and in its territorial waters, a different kind of wildlife abounds. Despite the boom in wildlife photography in India, our magnificent marine biodiversity has barely been explored. Sumer Verma is one of the few underwater photographers looking to change that.

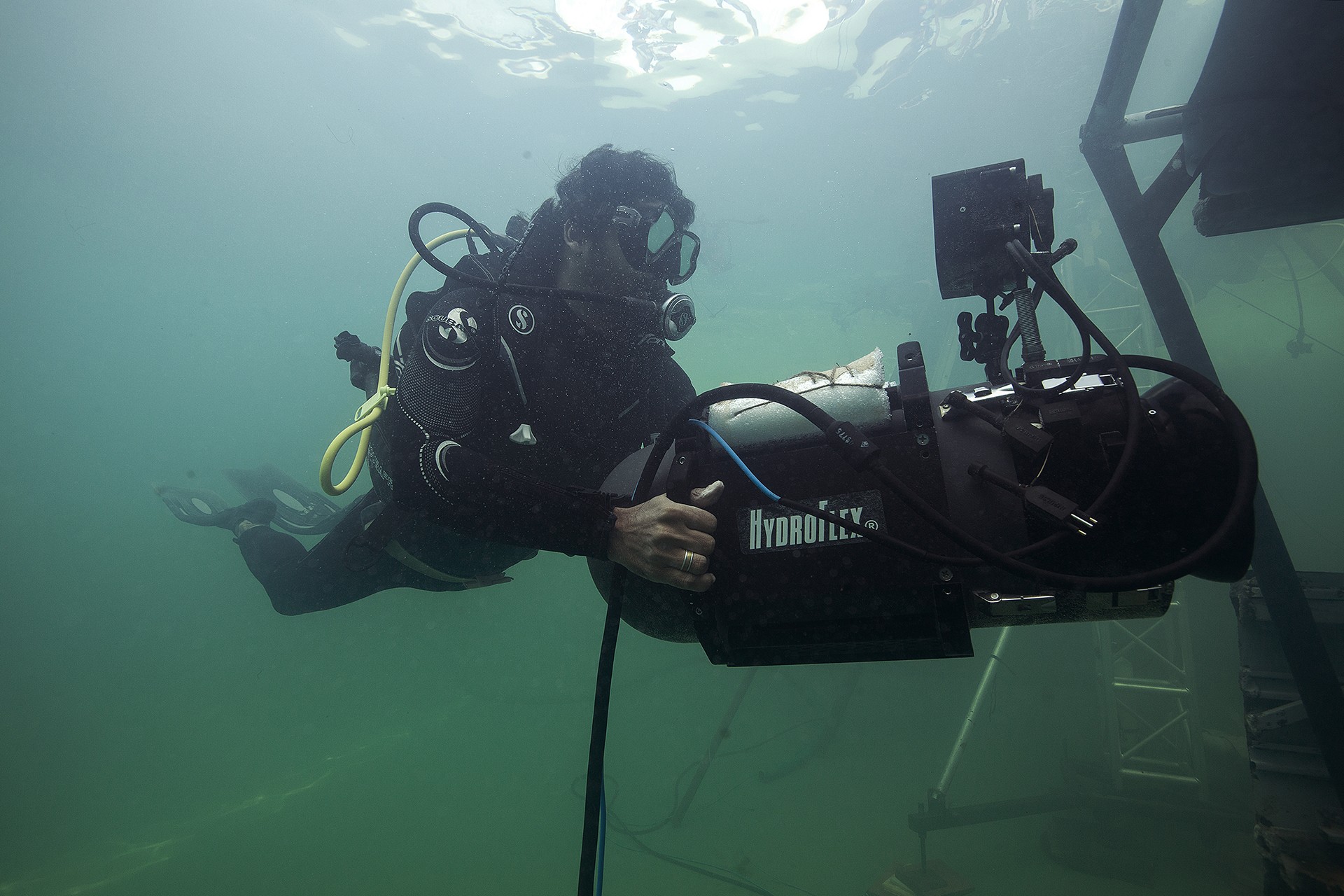

A veteran of the deep seas, Verma is the managing partner at Lacadives India, which set up the country’s first dive centre, and has completed 6,000 dives over two decades, after one transformative trip to the Lakshadweep islands off India’s west coast, in 1997. He has championed the cause of the sea turtles that nest on India’s east coast, and has worked with organisations such as Reefwatch Marine Conservation to highlight the damaging effects of global warming, especially coral bleaching.

Verma tells us about his own journey into the seas, the growing popularity of underwater diving in India, and how to make it as an underwater photographer. Read on.

You’ve said often that it was your trip to Lakshadweep in March 1997 that turned things around for you. What did you experience there that left such a powerful impression with you?

Well, I was just a guy from Mumbai, and apart from travel to places like Ooty, I had never really experienced nature in its pristine form. So when I made the trip to Lakshadweep, it was a huge eye-opener for me. The idyllic beauty there – its white sandy beaches, the varying shades of turquoise in the lagoon, the inky blue waters beyond, where you can still see 20-30m below when underwater – has to be seen to be believed.

I had gone there to undertake an underwater diving course, just as an adventurous experience to enjoy along with friends. But from the moment I put on that eye mask and dove underwater, I was awestruck. Water crystal clear almost as if I was looking through glass, and such a diversity of marine life that I felt I was in an aquarium, but this was the ocean!

Back in Mumbai, my mind still kept wandering back to what I had experienced, and that’s when I decided to make diving as part of my life. I spent much of the next 15 years at Lakshadweep – undertaking more advanced courses through CMAS (Confédération Mondiale des Activités Subaquatiques) which was the premier federation for certification at the time, although PADI (Professional Association of Diving Instructors) is most widespread now. From 2000 until 2010, I worked full-time at Lakshadweep, teaching, diving, and revelling in the beauty of the place. Since then, my attention has shifted to the Andamans, where, through Lacadives, we began preparations to set up our second dive centre.

Why are there so few underwater photographers in India? Is it a lack of exposure, a matter of affordability, or are there other constraints?

It’s a combination of the factors you mention. Indians generally have never been very comfortable venturing into the sea, even with such a vast coastline. Forests have been more accessible, and so we see a greater number of people venturing into nature photography there. The very first requirement of being an underwater wildlife photographer is of course to be a scuba diver. After seeing my images, a lot of people call me to say they want to start underwater photography, but the first few questions they should ask themselves is: do I know how to swim? Do I know how to dive?

With underwater photography, you have to make that commitment to do a scuba diving course, which is expensive. You have to travel to places like Lakshadweep or the Andaman islands, and only after that can you think about venturing into underwater photography (and the equipment is expensive). There is serious investment needed – whether it is time, effort or money.

Do you think India is ready to be a tourism destination for activities such as scuba diving? Are there any negative perceptions people have of diving in India’s waters?

When diving started in India, there was a lot of skepticism about how professional the diving operators might be. It can be a life-threatening activity so there was a natural concern about whether equipment would be properly maintained, and so on.

But I’m proud to say that Lacadives, in more than 22 years of diving and training more than 10,000 people, has never had an accident, which frankly is a better record than many dive shops all over the world. Overall now, the level of diving is pretty good and there is now increased confidence in the dive shops here in India. Scuba diving is primed to become one of the mainstream adventure sports of our country, and the number of underwater photographers will grow with that, it’s a natural progression.

Of course, today with travel websites more focused on mass tourism, local operators are also seeing this as an opportunity to make a quick buck, and due to the low quality of equipment and training, accidents do happen, sometimes even resulting in deaths, which unfortunately paints the entire diving industry with a negative brush. This is where the administration should play a strong role, and make a clear distinction between the professionals and the fly-by-night operators, and take stringent action against the latter.

You have been diving for nearly two decades now. Have you seen changes over time in any of the specific sites you visit regularly? Is tourism starting to affect these sites?

There has been a drastic change from when I started diving to now in 2017. Ironically, it only took me one year to see it. In 1998 there was a very bad El Niño, 95 percent of the coral I saw had bleached and died. From 1998 to 2010, there was a very small recovery, but then the same thing happened again. And again in 2015. There has been tremendous wear and tear to the reefs, but I don’t really ascribe local factors to this. In 1998, Lakshadweep was pristine, tourism had barely touched it, and yet the damage was so great. The reason was global warming. It’s a misconception that divers cause harm to the reef, in fact they are the greatest ambassadors of ocean awareness and conservation, and you can be assured they will not be part of the problem because they are sensitised to this beauty, this biodiversity, unlike others, for whom it is easy to throw trash into the sea, without knowing what is under it and where it actually goes.

The problems faced today are catastrophic but they are global in nature, whether it’s increasing carbon dioxide causing acidification, the toxins which are dumped in the sea that eventually poison fish, and of course the way we fish, which leads to so much waste. Just look at shark finning. 70-80 million sharks dying every year, what statistics are these! There is endless blame game, from the hunters who won’t stop finning them, to companies like FedEx who will not stop shipping them to the Chinese who will not stop consuming them. It really is an alarming situation.

The seas are in a bad state, and the only way to move forward without being cynical is to educate people about it. One way to do that is make prints of images, have exhibitions, do up commercial spaces with them, so one has to be creative about how to get your work out there. You don’t have to be commissioned by only top publications like BBC or National Geographic to get paid and put your work out to people – there are other ways, too, such as making marine life documentaries for conservation organisations, which I’m looking to get increasingly involved with.

You have also added underwater fashion photography to your portfolio. What made you look beyond marine life?

That was by chance, really. I wanted to do underwater photography at all costs. It is a highly ambitious dream but I was quite determined. I had been a diving instructor for 10 years, and wanted to do more, but the sad part is that wildlife photography doesn’t really pay, and it really is near-impossible to make a living from it. Of course, there is great joy in getting your image on the cover of a magazine, or in an article, but frankly a few hundred rupees per image really isn’t going to cover much. So I had to expand to other forms of underwater photography.

I was inspired by Howard Schatz’s brilliant underwater fashion shoots – the dreamy space when you put a human underwater, the way the clothes, the hair flows, the weightless feeling you experience. I felt it was very profound, very beautiful. So I gave it a shot, and after a fair bit of trial and error, I got an opportunity from Vogue magazine to do some shoots. I went on to do more and more of these.

Sumer Verma’s guide to getting started on underwater photography:

1) Do your PADI Open Water and Advanced Open Water courses back to back so you get comfortable with diving and are able to control your camera.

2) There is great resource material online these days, so it’s important to read to understand the limitations and challenges with underwater photography, with water as the medium. Of course, you will need a lot of practice.

3) A compact camera with housing and a small flash can also get you very good results, and is ideal for beginners, as handling the heavier equipment involved with a DSLR kit is itself a task, and one must be a competent diver to handle such a heavy rig (the last thing you want is for the equipment to damage the reef and risking your life). The starting budget for this would be ₹30,000-45,000.

4) If you are looking at a reasonably versatile DSLR kit, look at a wide-angle lens, say a 16-35mm, a macro lens, either a 60mm or 100mm lens, 60mm being a more versatile focal length, strobe lights, a dome port to house the wide angle lens, a flat port for the macro lens. All in all, with some of the inexpensive brands, you could look at an outlay of ₹1.5-2 lakh for just the housing, ports and strobes.

5) As with any offbeat profession, there are short-term challenges, to keep sustaining yourself when you don’t have a gig for months at a time, or when you’re in the doldrums. This is when you must persevere, and not get disheartened and give up. Be patient, persevere, and try to be the best you can. If you do that, the results will come.

Sumer Verma showcased his work at the Nature inFocus Festival, 2017. If you missed it, or would like to understandably listen to his brilliant journey into the Big Blue again, here it is.