Armed with just a pair of binoculars and the curious ‘beating heart of a nine-year old’ (in his own words), Salim Ali changed birdwatching in India. Born in Mumbai, then Bombay, on this day 121 years ago, on 12 November 1896, Ali went on on to become one of the most well-respected ornithologists in the world. Even as a child, his love for birds could not be contested.

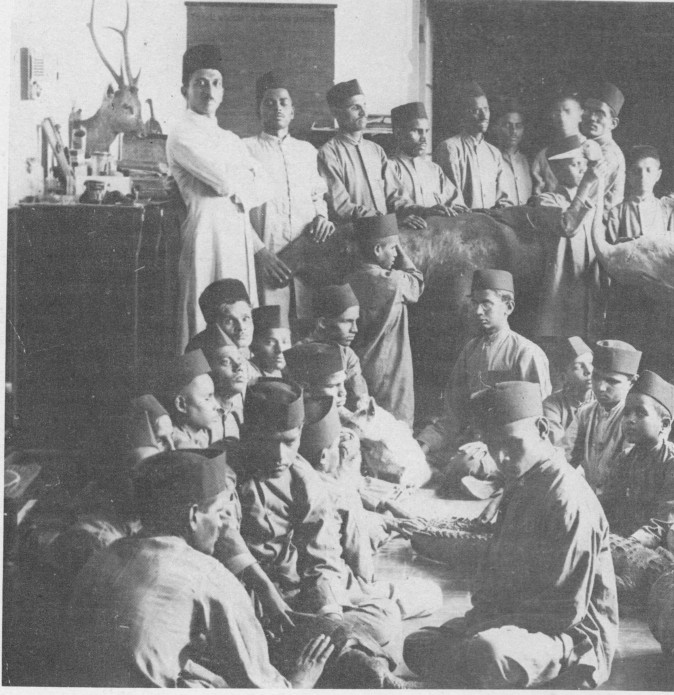

He was ten years old when his fascination with birds really took flight, and it was all because of a gun. His guardian and maternal uncle Amiruddin Tyabji, a nature-lover but also a keen hunter, had given him a toy air-gun. Young Ali shot a sparrow, which had an unusual streak of yellow on its neck, and his uncle was unable to identify the bird. He suggested that Ali take the bird to the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) for identification. That’s where Ali first met the Honorary Secretary, W S Millard, who identified the bird as the Yellow-throated Sparrow and went on to show Ali BNHS’ collection of stuffed birds. That is how his life-long love affair with birds began. It’s no surprise, then, that he chose to title his autobiography Fall of a Sparrow.

Ali did attend college in Bombay, but he soon dropped out and became involved in the family business of mining and timber in Burma (now Myanmar). But soon enough, he had to drop out of that as well; his work often took him to the thick forested Tenasserim of Burma, and he would often be caught bird-watching instead of focusing on the business! Back in Bombay, he took up the job of guide at the Prince of Wales museum. He also went on to finally complete a B.Sc in Zoology from St Xavier’s College.

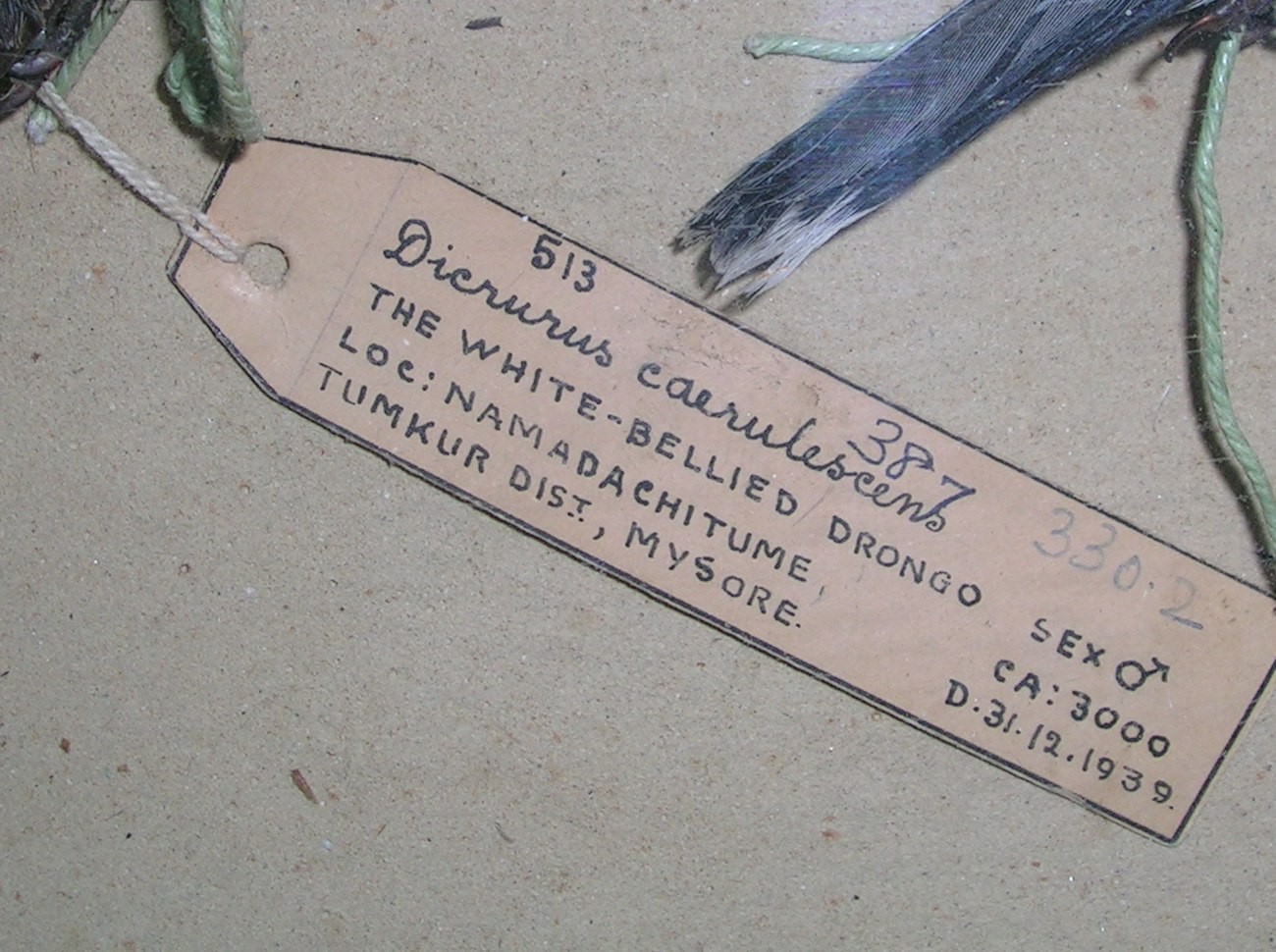

Next, Ali spent a year in Germany being trained by the famed ornithologist Dr Irvin Strassman, where he ratcheted up a good repository of knowledge and experience. But when he came back to India, he found that his position at the Prince of Wales museum was no longer available. He ended up moving to his wife’s house in Kihim, just north of Alibaug, where he would spend hours observing the place’s rich avifauna. His wife, Tehmina Begum, was his editor and one of his biggest supporters. A fellow bird lover, she helped him travel and camp out in remote areas. Tragically, he would lose her to a minor surgery gone wrong in 1939.

Ali was looking for a way to do what he loved, and get paid for it. He made a proposal to BNHS, the same organisation that had helped him identify the Yellow-throated Sparrow from his childhood. He would travel and record bird sounds in the princely states, if they covered his travelling and camping costs. BNHS, eager to improve upon their documentation, readily agreed. The results of this survey led to a groundbreaking paper published in 1930, which cemented Ali’s prowess and expertise in birds. The Book of Indian Birds, now a classic, was published in 1941. From 1964-74, Ali would produce his magnum opus, the ten-volume Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan as well, written in collaboration with S. Dillon Ripley. For his achievements in ornithology, he was awarded both the Padma Bhushan and the Padma Vibhushan. Salim Ali left us in 1987, but there’s little doubt that the mantle of birdwatching as we know it in India rests, even today, firmly on his shoulders.

For those of you reading this piece on the anniversary of his birthday, we’d encourage you to read Ali’s 1930 Frost-inspired essay Stopping by the Woods on a Sunday Morning. And in the meanwhile, let’s recall the varied legacies that India’s Birdman left behind:

Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS)

One of the oldest institutions working on biodiversity conservation in the country, BNHS was where Ali’s interest in ornithology first took wing. Always one to give back, Ali took over BNHS after Independence. During hard times, he reached out to Pandit Nehru to save the then 100-year old institution. Nehru approved enough funding to pull BNHS back from the brink. And when Ali received Rs 5 lakhs as part of an international award for his work, he gave the money to BNHS.

The Book of Indian Birds

The first and foremost bible of birdwatching in the country, responsible for the defection of thousands of ordinary citizens to birdwatching camp.

The Finn’s Baya

During his time in the terai region of Kumaon, he rediscovered the Finn’s Baya (Ploceus megarhynchus), a rare weaverbird species. Around the same time, he also began a search for the mystic Mountain Quail, though that did not prove successful.

Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History (SACON)

Following in the footsteps of India’s Birdman, SACON was set up in 1990 to “help conserve India’s biodiversity and its sustainable use through research, education and people's’ participation, with birds at the centre stage.” Today a Centre of Excellence under the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEFCC), SACON has its main campus at Anaikatty near Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu.

Salim Ali's Fruit Bat

Named after Salim Ali in 1972, Latidens salimalii is a rare megabat species which was first collected by Angus Hutton in Tamil Nadu in 1948. In 2002, Salim Ali's fruit bat was added to Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act, making it one of only two bat species with a high level of protection. Recently, in 2016, the Himalayan Forest Thrush was also named after him: Zoothera salimalii.

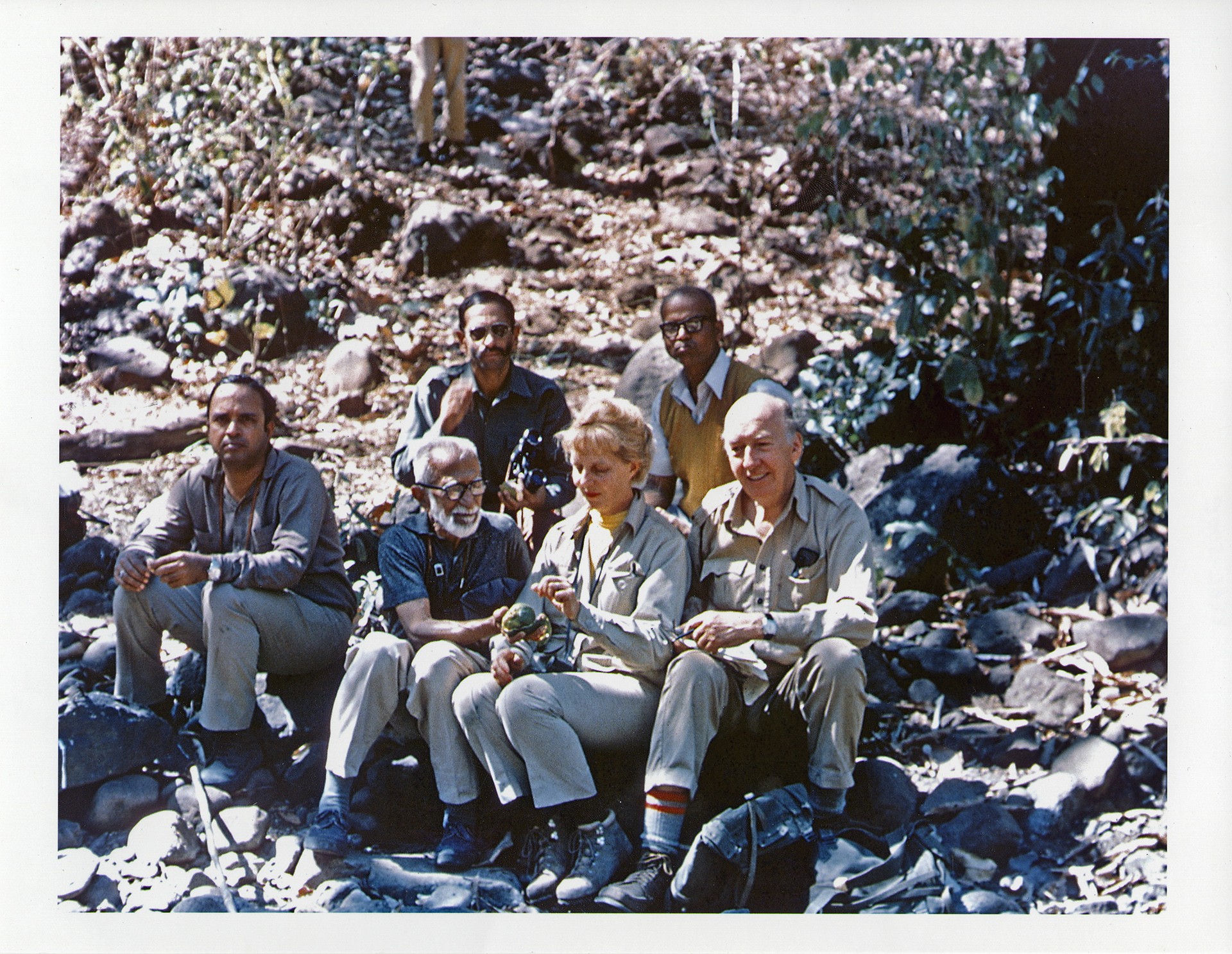

Silent Valley National Park

The movement to save Silent Valley Reserve Forest from being flooded by a hydroelectric project began in 1973. Dr. Ali played a big part in the declaration of the area as Silent Valley National Park in 1984 – he had earlier visited the valley and appealed for the cancellation of the hydroelectric project.

Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary / Keoladeo National Park

One of Asia's finest birding areas, Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary, now known as Keoladeo National Park, was designated with the help of Dr. Ali. Keoladeo is home to over 380 resident and migrant species and in 2010, the Salim Ali Visitor Interpretation Centre at Keoladeo was conferred the Best Asian Wetland Centre Award.