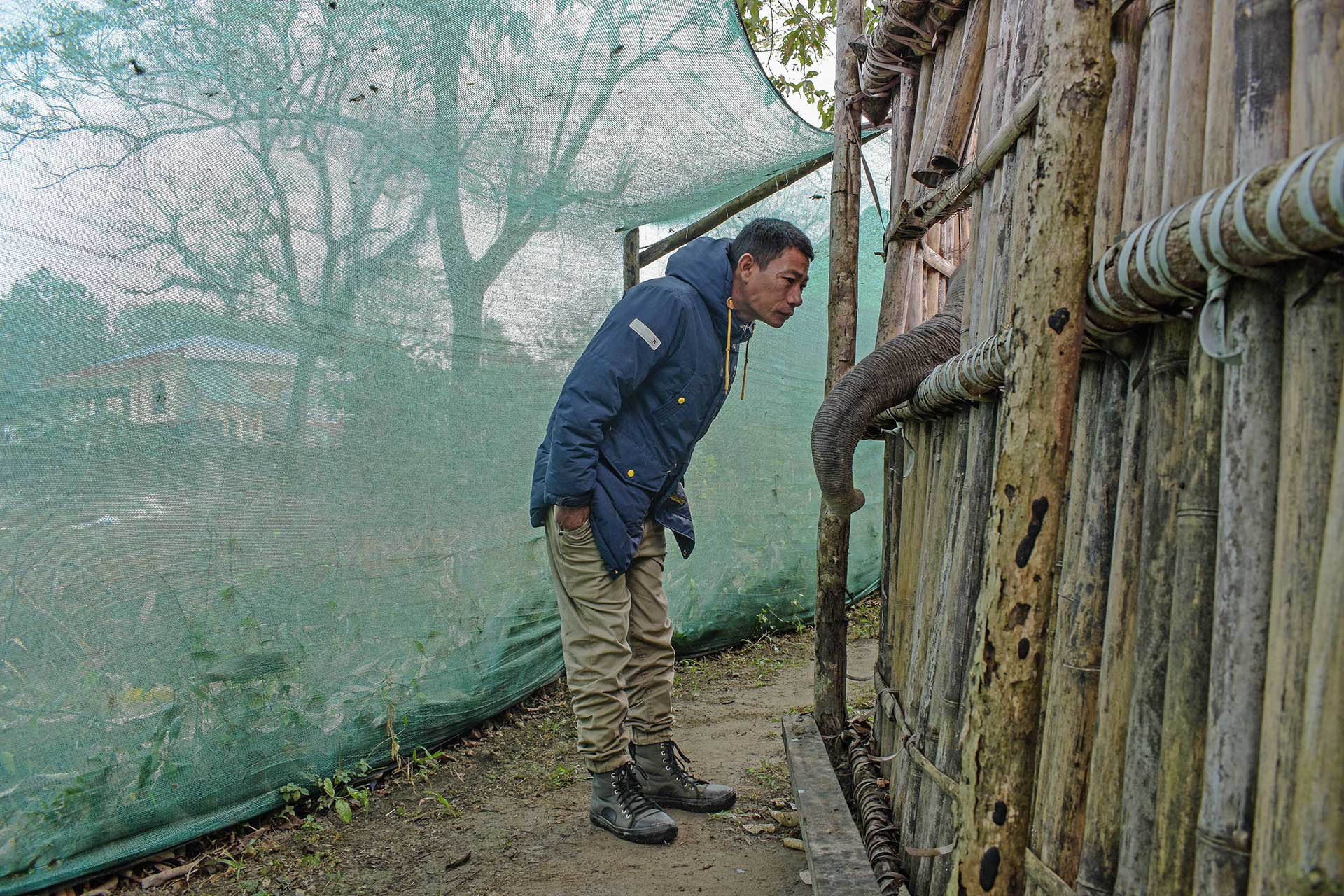

A year had passed since I last sat in the pink-coloured bus from Tezpur to Seijosa. Yet somehow, its jerky rhythm still felt familiar. After hours of dancing to the tune of the road, the fading daylight hinted at our proximity to the Assam-Arunachal border. Once the bus finally groaned past the military green checkpost at Seijosa in the East Kameng district of Arunachal Pradesh, familiar sights of roosting Wreathed Hornbills and a beaming Rasham Brah greeted me at Darlong Village outside the Pakke Tiger Reserve. An expert elephant handler, Rasham, who belongs to the Nyishi tribe, works with the forest department as a caregiver for Pakke’s camp elephants. Without his enterprising presence, none of my early explorations of Pakke Tiger Reserve could have ever taken shape.

The turn of the year had brought a military jeep for Rasham. The tall segun tree by his namlo (house) was gone, and wooden pillars now held a shade above his jeep. In a departure from Nyishi practice, Rasham's residence now sported raised wooden beds. But the squarish oven with firewood suspended above it, remained unchanged. Rasham's family sat with me in a ring around the warmth of the fire. Gatherings in such traditional kitchens are central to the Nyishi identity. Modernisation had seemingly yet to arrive in the Nyishi kitchen. Chilly winds, however, arrived freely, and even in the second week of February, the fire felt necessary.

During my previous visit, Budhiram Tai, the Gaon-Burrah (village head) of Darlong, had talked of a mythical world that elder Nyishi tribesmen held within them. It was a world governed by an enduring spirit of coexistence—the Pakke of old, before it had become a tiger reserve. I had been so overwhelmed by the contemporary realities of Pakke that reminiscence had eluded me back then. This time around, I wanted to try and tap into the elders’ memories and understand the ancient ways of Nyishi tribesmen.

Ashok Tallong, a young Nyishi man from the Bally Village, volunteered to assist me in my endeavour. He knew elders from his village but wasn't sure of what needed to be asked. As we sat discussing the possible means of our intended exploration with Rasham, details of a football tournament reached us over a loudspeaker from the Darlong playground. All of us realised that the whispering forests in an elder’s memory weren't going to be so loud.

A rainy morning ensued, and Rasham laughed off my hesitation in visiting his ailing father so early in the day. "Old men wake up long before the hornbills," he said. When Rasham introduced us, Japa Brah was preoccupied with his knitting. "Do you remember stories of how Nyishis lived in harmony with the forest during your days and in the days of your father?" Rasham asked. His query elicited a muted response from his father, "What stories would I know? Back in our day, we knew nothing." Japa ran trembling fingers over the furrows on his beardless face and pointed at me, "We ran away from bearded people like you in those days." A toothless grin spread across his face, "Our clothes were scanty, mostly leaves and animal skin. We didn't even know about oil or milk."

Rasham left for work, but Japa went on, "Before the Indian government showed us the ways of the world, we only knew whatever little our elders preached—foraging for wild vegetables across seasons, farming in the hills, and hunting. Vegetables, fish, meat and apung (a smoky alcohol drink)—there was nothing more to our world." "Do you remember when you started going to the forest?" I asked Japa. "I learnt to navigate the forests even before I learnt to talk," Japa's words carried soft rebukes. "You see namlos, roads, schools and hospitals today. None of that was there. There were forests everywhere. I still remember every trail across the hills, but my legs aren't strong anymore," Japa said as he felt the region around his ankles. "We went hunting and foraging with elders whenever they called us. At other times, we went to the forest all by ourselves."

When I asked Japa about his experiences in the forest, his memory began to flow like a river during the monsoon, "Oh! I used to meet the bandor (monkey), pohu (barking deer), junglee mithun (Indian Gaur) and haathi (elephants). The mekuri (small wild cats) always lurked close, but they rarely showed themselves." Japa talked of Pakke's songbirds, civets and iconic hornbills, of edible fungi and other unique flora. Then, amidst the tangle of memories, a tiger emerged. I was eager, but Japa's words on the tiger were careful, "Let me tell you, son, only the most courageous can endure standing before one." Only after he explained how we humans had disrespected our mythical brotherhood with the tiger did the memories resurface!

Japa talked in a hoarse whisper, "Where the school stands today, it used to be a dense forest. On a narrow trail, I was following fresh pugmarks in the mud when the tiger emerged from the forest to my right. His head was bigger than you can imagine." Japa stretched his hands to elaborate, "Such huge paws, rippling with strength! Only the elephants are stronger!" Japa had loved following wild elephants. They showed him secret trails in the forest. But once, while doing so, he had stumbled upon a leopard preying on a saarchi (Yellow-throated Marten). Japa's shouts had sent the leopard away but irked the elephant. He then had to hide in a nahor (Mesua ferrea) tree until the elephant's frantic trumpeting had ceased. Japa has lived through many such episodes. He had once run back home after accidentally sitting on a python. Still, he describes that moment of facing the tiger as his scariest memory.

This hushed reticence towards the tiger was not Japa's alone. When Ashok took me to Bally to meet Tana Takkar, the adept forester told us that tigers also avoid making eye contact with humans in the forest. Takkar had chanced upon a tigress with her cubs near Dicho nala. The mother had a subtle way of maintaining her watch on Tana, but the interest among the curious cubs had been far more apparent. "The small ones were yet to learn the truth of our relationship," he said. Tana reiterated the story of our broken bond with the tiger. Not just the tiger, Tana believed that the leopard, "the black one" (melanistic leopard), and "the smaller one" (Marbled Cat) were all equally apprehensive of humans. Once in his lifetime of roaming the forests, Tana had chanced upon a Black Panther resting under the winter sun, "but it disappeared so fast that the sighting had almost felt unreal."

You may also like to read

Akin to the melanistic leopard, in the darkness that shrouded Tana's namlo that night, Tatang Tachang's presence, too, was hardly discernible. Tatang rarely spoke but occasionally rekindled the fire. Maybe Tana's recollections of the forest rekindled his memories. Tatang, like Japa and Tana, had roamed the forests of Pakke since childhood before working as an STPF officer for over 20 years. Yet, he had never seen a tiger.

Tigers and leopards, however, continue to occasionally prey on cattle that venture across the cobalt-blue Pakke River, which separates Bally from the tiger reserve forest. I longed to see this river and the nursery of Golden Mahseers that Ashok kept talking about. But the night hid everything. All that existed were dimly lit shapes of a world that Tana and Tatang conjured—a world of bows, arrows and deer traps where traditional wisdom sustained the tribe.

"Up in the hills, where tigers are larger, you find plants with venom that can kill elephants," Tana whispered. He remembered his father's lessons on tipping arrows with such venom. "My father used to build an elaborate marang (wooden maze) over our farmlands," Tana had been taught this art of cornering trespassing boars and scurrying field rats. Tripwires, set high in the trees, deterred invading monkeys. Tana had once witnessed a macaque get impaled in such a trap with her baby held to her chest. He had found their death hard to accept. 'How else shall we protect our crops?' Tana had been rebuked! Misplaced emotions were a threat to survival.

Tana never taught his son about tipping arrows or laying traps. It felt comforting until Ashok explained the truth, "We gave up carving bamboo only because we were handed guns." Along the pitch-dark road from Bally to Seijosa, he spoke of how their relationship with the forest was forged in subsistence. 'Feed the family, and I shall give up hunting!' Ashok's father had refused his suggestion of exploring other alternatives.

When the forest department suspended the contractual employment of Nyishi workers for an entire year, Rasham had been forced to live off the forest. But the proliferating algae in the river hinted at a plummeting fish population, and the fragmented forests of Seijosa, beyond the restricted tiger reserve area, held little bounty. An uphill drive to Jolly showed glimpses of how these forests once looked. Rasham and I wandered into Langka across a footbridge that hung over the expanse of the Jolly nala (river). It swung to the rhythm of our steps. A hilly trail flanked by bhelus (Tetrameles nudiflora) led to the Langka Beat Office, perched precariously on the edge of a precipice. Here, the forest was dense, and the drop-down to the riverbed was daunting. But elephants had still found their way into forester Dungro Natung's pineapple orchard. While treating us to the last remaining fruits, Dungro reminisced about Dholes that passed by his namlo and the tiger that crossed his path at Dibru nala two decades back. He then talked of Abo-Tani's (the first man of Nyishi folklore) mischiefs and of the songs of pipiar, pako-tabo and pingchang-tabo (various species of cuckoo) that ushered the sowing season in Nyishi folklore—while Rasham basked in the glory of discovering two perfect pineapples amidst the crumpled orchard, which both Dungro and the elephants had failed to locate.

On the sparkling day that followed, Ashok and I searched for Taking-Taring's mythical prowess of archery. Beloved sons of the first man, Abo Tani, Nyishis trace their practice of archery back to Taking-Taring, but few remember the exact unfolding of their mythological lives. Whoever we asked redirected us to someone else. The Gaon-Burrah's fragile health kept him from speaking. He suggested we try our luck with Radak-Burrah, who we found curled up by the oven. "He had too much apung last night and won't be up any time soon," his son said with disdain. With our last hopes doused in apung, we decided to pay a visit to the mahseers. Sopia, a white-brown pup, accompanied us to the expansive riverbed.

Wading past tadpoles in shallow streams, waiting for the monsoon to reunite them with the gushing flow of the Pakke River, we reached a sandy shore. A cliff rose at its edge and gradually grew closer to the river until its vertical wall almost touched deep, gurgling water. Ashok’s traversal of this treacherous bouldery trail was intuitive, but I was constantly wary of slipping. Losing balance could mean a fateful fall into the roaring depths of the Pakke River. Sopia and I struggled with confidence the entire time, and we breathed sighs of relief once he finally signalled for us to stop.

Amidst a labyrinth of boulders, dark shapes scurried in shallow, sheltered water. But the river was deep and mysterious beyond it. Intrigued by pebbles flung by Ashok, sleek shapes momentarily broke the water's surface before retreating to invisible depths. These were the Golden Mahseer. At a distant bend of the river, a solitary Grey Heron quietly fished. Elephant droppings at the forest's edge beckoned us to cross the river. But the water had reached up to my waist, and the current felt strong. Under my feet, stabbing pebbles were friends. "They might hurt a little, but you are going to slip on the smooth ones," Ashok issued a warning. Entering Pakke alongside Ashok as we waded across the river felt very different from the usual ritual of permits. With him, the forest felt like home.

This is the first part of a two-part series about Pakke before it became a tiger reserve, as told by elder Nyishi tribesmen. You can read the second part, here.