Last year, before the much-publicised total solar eclipse on August 21, NASA invited people to record the moment the Earth crossed the shadow of the moon, using the NASA GO app. Through the app, people could collect data on clouds and air temperature on their phones, which would later help scientists determine the impact of an event such as an eclipse on the environment. While the analysis is still underway, NASA received over 80,000 air temperature measurements and nearly 20,000 clouds observations from more than 10,000 observers!

For the uninitiated, citizen science (sometimes referred to as community science) is the collaboration of citizens with academics, research institutions, governments or community groups to monitor, track and record issues of environmental importance. After all, a large data set can be a powerful tool when we investigate the world around us. And it’s good to know that we don’t need a science degree to contribute to science!

In India, there seem to be new citizen science initiatives popping up around every corner. And alongside, there seem to be more and more citizens engaging with these projects. “When people see what a difference their participation makes, they become both more regular and committed participants, as well as become ‘ambassadors’ by reaching out to other people and audiences about the project,” says evolutionary ecologist Suhel Quader, who was one of the founders of MigrantWatch (more on this citizen science initiative later).

We decided to pick some of the most effective and engaging citizen science initiatives from across the country. So go on, step out and count birds and butterflies, monitor camera traps, conduct surveys or monitor local water quality. Use your computer, your phone or just your brain to take notes, and contribute to something that’s bigger than you. Here are eight initiatives you can be part of, starting right now!

eBird / MigrantWatch / Kerala Bird Atlas

Best for: Avid birders

In collaboration with Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF) and the Indian Birds journal, National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) ran MigrantWatch from 2007 to 2015. It brought birders from across the country together, and became such a comprehensive database of the 300 or so migrant bird species that appear in India seasonally, that it has now partnered with eBird. From just 700 observations of 9 species in its first year, there were over 30,000 in 2017, when the data from MigrantWatch was migrated to eBird.

It is because of MigrantWatch that we now know that the Rosy Starling, Pied Cuckoo and Grey Wagtail are the most commonly sighted migrants in India. Large data sets indicate that the Grey Wagtail makes its appearance in late August, and that the Pied Cuckoo, a summer visitor from Africa, does in fact reach us just before the monsoons (this was just folklore earlier; people believed that the thirsty chatak bird would appear and herald the approaching rains).

A number of other exciting projects are active on eBird as well, such as the first state-level atlas project for birds – an initiative hosted by Kerala’s bird watchers. It’s known to be an inspiration for other state-wide projects as well. Do check out this episode of The Intersection podcast for details.

So head over to eBird now and discover a whole new world of birding!

SeasonWatch

Best for: Tree lovers

Not all of us have the trained eye of a birdwatcher, but at least it’s simple enough to notice when a tree in your neighbourhood is in bloom or starts bearing fruit! Following in the footsteps of MigrantWatch, SeasonWatch is another citizen science initiative launched in 2011, which helps record the flowering and fruiting times of different tree species.

It started out as a fairly simple methodology limited to 100 common and 15 focal tree species, and now the program is being taken to schools all across Kerala. To involve younger generations and help them develop an interest in ‘phenology’ (the study of plant and animal life cycle events), SeasonWatch has partnered with the Mathrubhumi SEED program to involve school students from across Kerala. Students pick a tree of a certain species close to them, and monitor it once a week – noting any changes such as fruiting, blossoms or maturing of leaves. For instance, the Indian Laburnum or Cassia fistula is known for its profuse flowering, which gives it the name of the ‘golden shower tree’. Through this, they are able to observe the impact of climate change on seasonal changes in trees as well.

As of now, the trees with the highest number of observations on SeasonWatch are the Jackfruit, Mango and Amla trees. Head over to Google Play and download the free app.

India Biodiversity Portal

Best for: Researchers, naturalists and anyone else interested in more than just birds or trees

In 2008, five institutions led by Bangalore's Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE) launched a major crowdsourcing initiative to document as much of our natural world as possible – the Indian Biodiversity Portal (IBP).

IBP serves as an umbrella portal for data, information and maps based on an open-source model. In addition to being a data platform, IBP organises campaigns such as the recent Neighborhood Trees Campaign and National Moth Week. They also consistently add on map layers to improve the map-based functionality for researchers and enthusiasts – you could, for instance, layer a vegetation map of a particular habitat along with the location layer for a particular species, and you’d understand the occurrence patterns better.

Perhaps India’s answer to eBird or Zooniverse, IBP is a one-stop map-based platform for collaborative conservation. Much like its sister sites, India Water Portal or Indian Environment Portal (also managed by The National Knowledge Commission), IBP seeks to provide a far-flung online repository of the country’s biodiversity, mapping about 26,168 species and over 13 lakh observations, last we checked. Recently, the website was integrated with the Department of Biotechnology's biodiversity database, the Indian Bioresource Information Network (IBIN).

Citizen Sparrow

Best for: Birders and conservationists

Did you know that the common House Sparrow isn’t all that common anymore? Once a typical sight in cities, towns and villages alike, their populations have been in rapid decline over the last two decades. Till date, the project Citizen Sparrow, launched in 2012, has been able to gather 11,283 observations by involving 6,001 citizens across over 8,886 locations (at the time of writing this). It is because of this initiative that the urban decline of house sparrows was first understood and quantified. Based on data gathered over years, we now know that sparrow numbers have reduced in cities, relative to towns and villages. There’s variation between cities as well; Mumbai and Coimbatore still see a lot of these birds, while Bengaluru and Chennai have seen worrying declines.

As the team behind the project says – recording sparrow presence is just as important as recording absence. Unfortunately, this project is no longer active and not accepting new inputs, but it’s still a useful resource documenting the decline of a once-ubiquitous species. Citizen Sparrow is a brainchild of the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), NCBS and NCF. For more information on the project, go to their website and find out how house sparrows are doing today, or to download this cool printable poster.

Hornbill Watch

Best for: Researchers and conservationists

You can miss a forest for the trees, but you probably can’t miss a hornbill for the trees! Often called the 'farmers of the forest' for their role in seed dispersal, these brightly-hued birds are critical to the sustainability of forests in the Western Ghats and the Himalayas. The female is known to stay in the nest for upto four months, while the male works hard to bring back food for the mother and chicks. In many areas, they’re hunted for their beaks, feathers, meat and the horn-like projection on their heads, called a ‘casque’.

Launched in 2014, Hornbill Watch is a combined initiative by the Hornbill Nest Adoption Program (HNAP), NCF, Conservation India, the Ghora-Aabhe Society and the Whitley Fund for Nature, attempts to record hornbill sightings and images of the nine species of Asian hornbills found in India. As of February 2017, the program has collected almost 1000 observations from 430 citizens across 27 states. The data that’s collected will help prioritise important sites for conservation.

Lost Amphibians of India

Best for: Researchers and conservationists

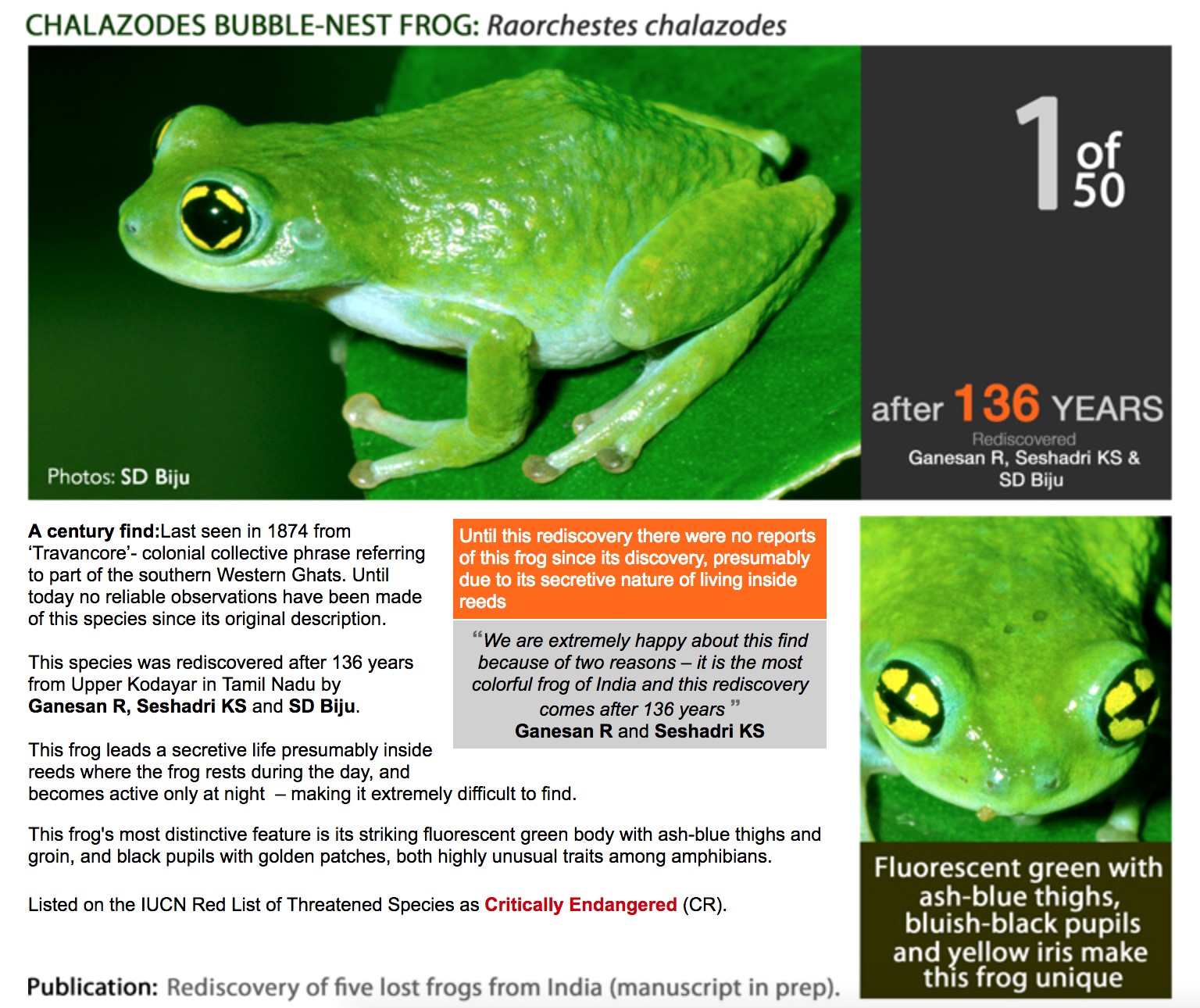

An initiative by the Systematics Lab at University of Delhi’s Department of Environmental Biology, Lost Amphibians of India (LAI) attempts to search for about 50 amphibians which were seen as recently as 18 years ago but can no longer be spotted.

In 2014, a team led by researcher S. D. Biju (also known as the Frogman of India) discovered seven species of Hylarana caesari or the Maharashtra Golden-backed Frog, highlighting the importance of areas such as Amboli and Koyna for endemic species of frogs. Earlier, in 2011, they had rediscovered five other species previously believed to be extinct, including the Chalazodes Bubble-nest Frog or Raorchestes chalazodes, which had last been spotted in 1874. Quite fitting then, that the question they’ve designed the LAI initiative, quite simply, is: “Are they really extinct or have we not looked hard enough?”

If you’re interested in joining their expeditions or finding out more, you can write in to [email protected].

Urban Slender Loris Project

Best for: Researchers and conservationists

Started by interdisciplinary scientist and educator Dr. Kaberi Kar Gupta, the Urban Slender Loris Project is a community-based conservation initiative for the Slender Loris – a Schedule-1 species locally known as the Kaadu Paapa in Kannada – in urban Bangalore.

Found only in Sri Lanka and Southern India, the Slender Loris or Loris tardigradus is a small nocturnal primate that’s primarily arboreal – it prefers continuous forest canopy that it can climb across. Looking at these unique habitat requirements, the project aims to determine whether they could be an indicator species for the overall health of an urban environment.

This has now grown into a full-fledged citizen science project involving transect walks and surveys in the night to monitor the absence and presence of slender lorises in Bangalore, and vegetation surveys in the day to examine habitat structure and human interference. In addition, volunteers conduct oral interviews with old-time residents of Bangalore, wildlife enthusiasts and animal rescuers to establish a clearer understanding of distribution and trends.

Some of the scientists involved in the project have been pleasantly surprised to find a healthier population in recent years, as compared to anecdotal reports from the past. The USLP database will be used for long-term monitoring by scientists.

Please visit our story on wildlife apps that you can use for conservation and the collection of data.

Editor’s note: Citizen science projects are a way to improve both the quantity and quality of scientific data being gathered both for academic research and grassroots conservation. As a data gathered, make sure that you’re following the guidelines and collecting information that’s as accurate as possible. If you’re a data user making use of one of these databases, ensure that the inputs have been verified and validated before applying the insights to conservation strategies or research.