This is the eighth and final story in a series of articles on the Andaman Islands launched by Nature inFocus in an attempt to showcase the natural history of these islands from the unadulterated perspective of its unique biodiversity. Each article from the series is titled with a line from J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings poem – “All that is gold does not glitter."

Long franchises, when stretched too far, often end at the very beginning; the origin story. The story of my love for the Andamans started at a different place – the Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuary in Karnataka. For my masters’ thesis work with a biodiversity research lab in Bangalore, I had two options – to study the interesting interactions between cattle and forest in the Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuary or head out to the Andaman Islands to study newly introduced deer. The former, situated right outside Bangalore city and the latter, an expensive flight away from the mainland. I couldn’t afford a visit to the island, so I headed out to Cauvery for the weekend, to help myself make a decision.

Cuavery was a truly remarkable landscape, and I came out with not as much as a mosquito bite. Alas, for all its magnificence, it didn’t imprint on me as much as my previous field site in the evergreen forests of the Eaglenest Wildlife Sanctuary in Arunachal Pradesh. I had come out of summer fieldwork trips riddled with boils – thoughts of which still make my skin crawl, eight years later – and the Andamans had a similar reputation. And to add to this, there were absolutely no native mammals in the Andaman landscape. It would be a shame to waste the prime years of one’s youth in a bland forest where malaria was the only scope for excitement. But on an impulsive evergreen bias, I chose the Andaman Islands, quite irrationally and without having ever visited. Almost exactly five years later, I’ve missed out on hundreds of impressive sightings and I look forward to missing many more.

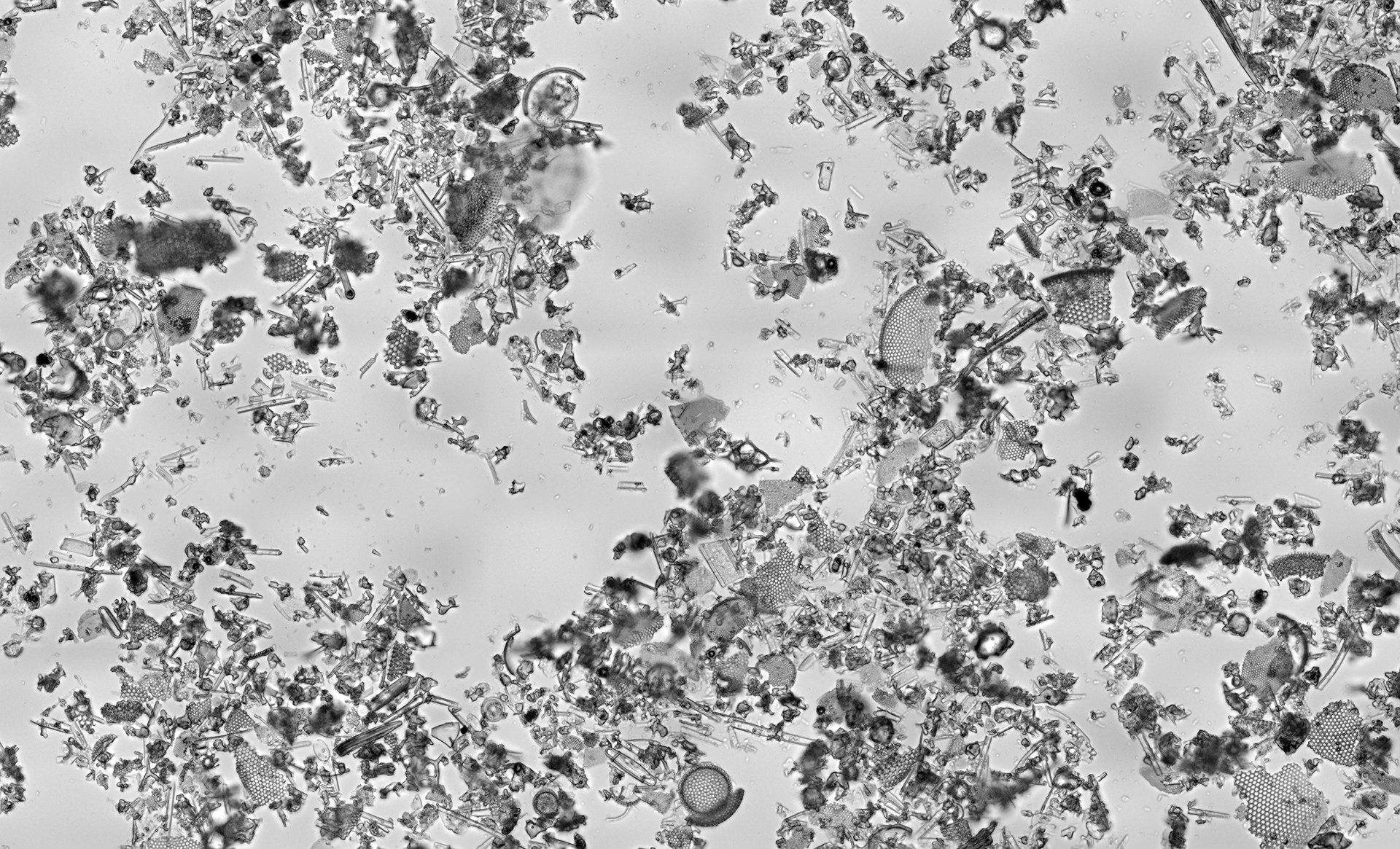

We spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about charismatic fauna like elephants and tigers, while the most diverse group on earth is in fact, microbes! All microbial classes together have 40 times the total mass of all animals on earth combined. In fact, they have the second-largest share of the total biological mass on earth, second only to plants, making studies of their diversity hugely important. The Earth Microbiome Project, which published its results in 2017, reported estimates of more than a trillion species of microbes. That is 'one' followed by 12 zeroes. This project was the largest, and perhaps the first, of its kind, where samples of soil, sediment, animal and plant material were crowdsourced from diverse ecosystems across the globe. The DNA in the samples were processed in laboratories in the United States to find that only 15% of the DNA could be identified. So, as of 2017, deep into the scientific revolution and 50 years after the first manned mission to the moon, 85% of the microbial diversity on Earth remains uncharted; unconquered.

Perhaps this is all a trivial affliction. Maybe we know little about microbes because they are in fact uninteresting, ecologically speaking. Indeed when you think about the vast outdoors, be it forests, coral reefs, lakes, savannahs, you associate them with large mammals, birds, reptiles, tall trees, colours, calls, behaviours. Microbe sightings don’t really feature in your next holiday itinerary. In fact, even conservation efforts are known to be biased towards animals that humans consider beautiful, Instaworthy, or just animals that look like us. Microbes, which are basically bags of molecules, rank abysmally in conservation consciousness. To complicate things further, they feature commonly in disinfectant advertisements, pamphlets about communicable diseases and in general, get a lot of negative press. But these disease-causing microbes are only a small fraction of their total diversity on earth. Several “helpful” groups make our cheese, brew our beer, curdle our milk and even digest most of our food living inside our guts. But their seminal work is in the field of ecosystem functioning.

Climate’s little helpers

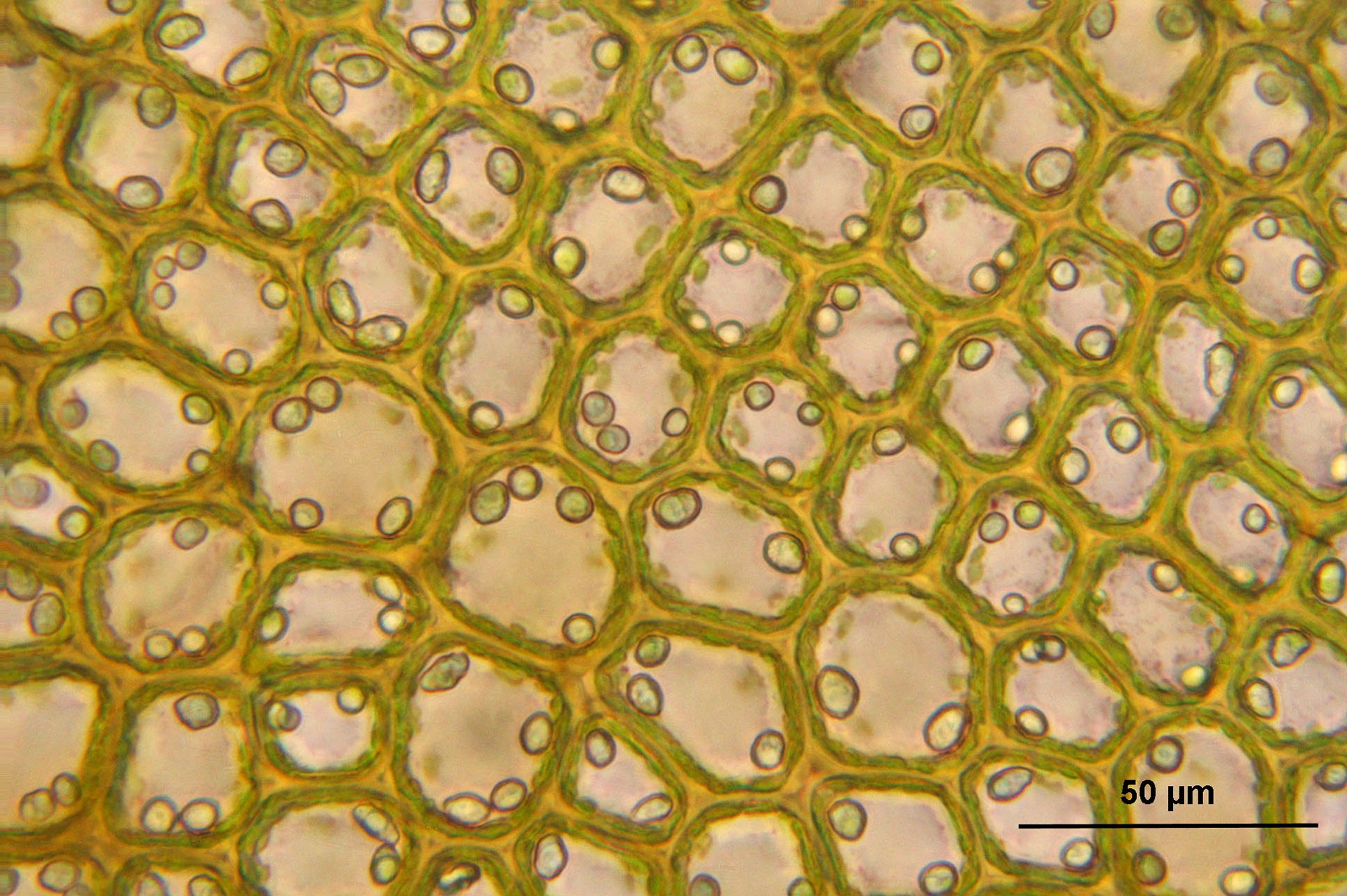

The integrity of every single ecosystem that we know and love hinges on microbial processes. Ecosystems maintain themselves by cycling nutrients – carbon, nitrogen, phosphorous, potassium et al. – and water, between their many components. These resources move from the soil, water or air, into the biological realm through plants, pass along the food chain, and return to the soil, water or air through the decomposing organic matter. The growth of a forest depends on how fast it can uptake these nutrients. In the context of climate change, we value this growth rate, because a forest that grows faster soaks up carbon dioxide faster from the air and decreases global warming. Tropical forest trees rank really high in this regard, but this ability of a forest to grow depends not just on the trees, but the fertility of the soil.

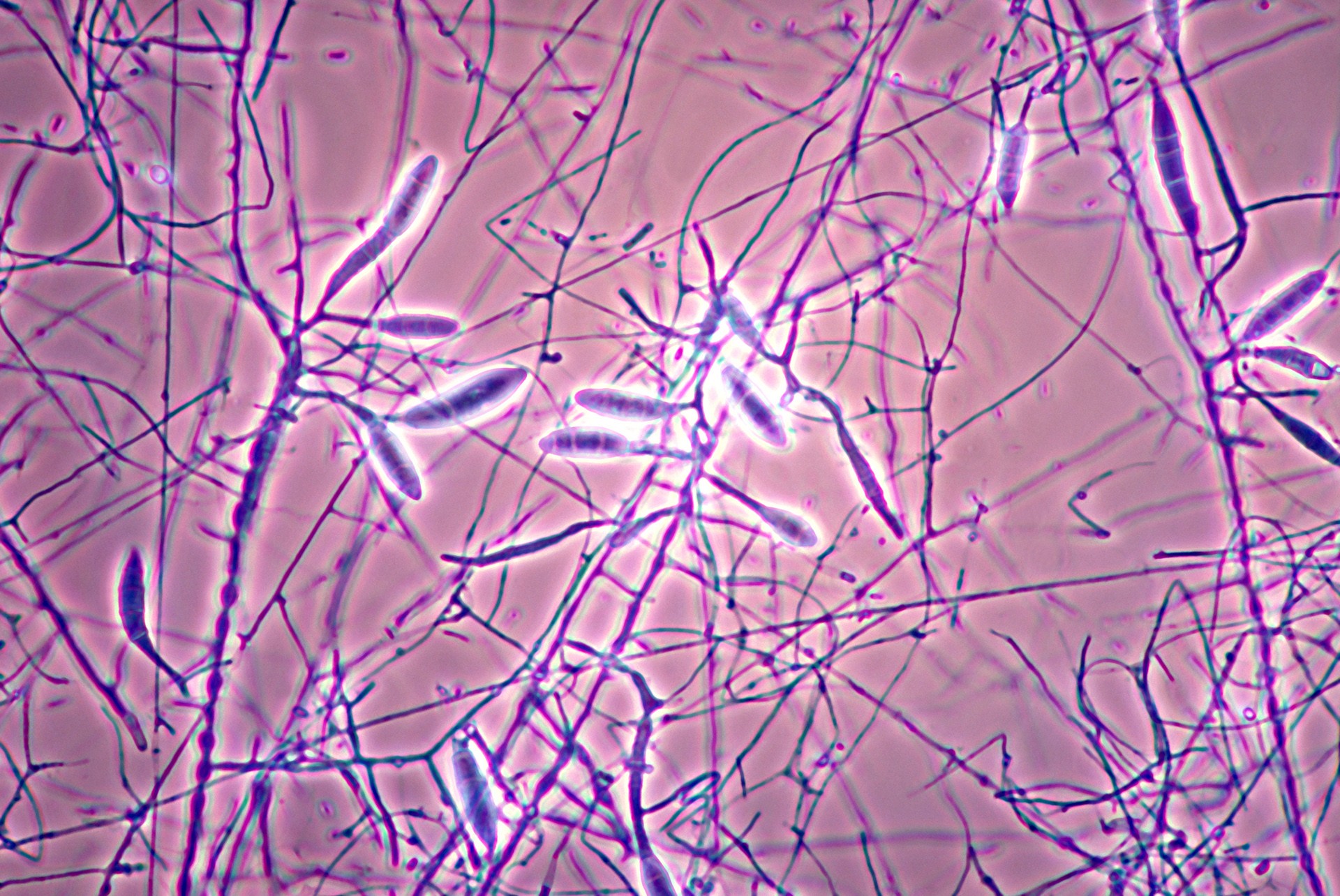

Forests cannot sustain a fast growth rate unless nutrients that are used up are continuously replaced in the soil. The entire task of replenishing nutrients in the soil, either from decaying organic matter or by fixing nitrogen from the air, is performed by microbes alone. Nitrogen, although makes up 78% of the air, is limited in the soil and this is because only a few groups of microbes have the tools to break up nitrogen from the air into compounds that plants can absorb. Behind almost every growing forest are nitrogen-fixing bacteria setting up the stage for plant growth. Similarly, a few larger animals are involved in breaking down dead matter and refuse, but the final process of converting them to nutrients is completely microbial. Microbes in the soil respire, digest bits of organic matter and secrete important nutrients for plant use. These microbes, in a sense, are the top of the food chain; they eat even the top predators when they die. Through their effect on soil fertility, microbes pull the strings on how much forests can grow and thereby, the future of our planet's climate.

Decomposition is a gaping hole in our understanding of climate change. To set this right, researchers from the Wageningen University in the Netherlands developed a simple, low-cost protocol to estimate decomposition rates. Because the method only involved burying standard brands of tea bags in the ground and measuring the weight remaining in a few months, anyone across the globe could participate in the project and calculate the “Tea Bag Index”. With the first set of data, they found that dry tropical forests, globally have the fastest decomposition. Wet tropical forests, like the Andaman Islands, though have high decomposition rates on average, these rates are variable when you compare across different forests. However, this is only a fraction of the data necessary to understand future climate. For instance, mangrove and littoral forests are known to have some of the highest rates of nutrient cycling among all ecosystems because of tidal flux. In a matter of days, a piece of paper that you drop in the mangroves can disintegrate into the nutrients that its parent tree had consumed. Questions on what the actual rates are and how they compare with other coastal regions across the world are waiting to be answered.

The Andamans grow on you as you stay there. But so do microbes. They make their way to the clothes in your trunk, leaving black spots, to the slight damp inside of your electronics, and even on to your skin. The willingness of microbes to grow is dangerous for the callous, often unhygienic, field ecologist. Every exposed wound is prone to infection and infected they become. You can battle them with any combination of neem paste, hysterical doctors, and flight tickets out to the mainland, but they check back in once you are back on the field. I know now that I will never win against the microbes of the Andaman Islands.

To read the first story in the Andaman series click here.