“You’re sure you saw them?” I asked.

“Very sure. They were huge, swimming alongside the boat for a long time. They were also the boldest sea creatures I’ve ever seen.”

“Did you manage to get them on video?!”

“I did, but I’ve lost those files…” came the reply.

I was chatting with Om, a fisherman from the Goa-Karwar region. He was telling me about a marine animal that is known to inhabit Indian waters – including those of the west coast – but of which there are few verified sightings. Om’s account, and his description (he called them “dolphins the size of whales”) seemed unmistakable. He’d seen orcas in the water, also known as killer whales. But there was no evidence to prove it.

The orca, or killer whale, is the largest of the dolphins (yes, it belongs to the dolphin family), and is so widely distributed globally that it is thought to be the second most widespread large mammal on the planet – the first being, of course, humans. The world’s orcas have diversified to suit the environments they live in, with each population having evolved different kinds of behaviours and hunting very specific prey (for example, fish-eating orca populations won’t eat mammals, and vice-versa). Four distinct ‘ecotypes’ of orca are known based on such differences. However, to this day, not much is known about this species in Indian waters. As with many others who are drawn to the fascinating world of marine mammals, I too was first smitten by the orca, and it became one of the beacons that attracted me to this field. My fascination with this species in Indian waters began in 2011, when an astonishingly close sighting of three orcas, including a massive male, was reported from the busy Vasco harbour in Goa by Ajey Patil, a dive instructor. Soon after, he logged another older sighting from Netrani Island off Karnataka, where he was told that orca sightings – albeit unpredictable and sporadic – do happen every once in a while.

But it wasn’t just orcas. I wanted to know more about the marine mammal diversity that exists all along our west coast. The territorial seas of India are an immense expanse of blue, woefully under-explored from a wildlife perspective. I currently study the interactions between coastal fisheries and Indian Humpback Dolphins – fascinatingly clever, adaptable animals that have always intrigued me. The Indian Humpback Dolphin and the Finless Porpoise are the two strictly nearshore species that together form the focus of a large chunk of marine mammal research along the country’s coasts. In fact, they are the most commonly spotted marine mammals along most of the west coast, and they are the species I see most frequently at my field site in Karwar.

Many kinds of whales and dolphins are said to exist in the waters just farther offshore. There are anecdotal stories of spectacular sightings, and every now and then live animals and carcasses wash up on beaches, but the zone they usually inhabit is a tad too far for a handful of researchers with limited resources to survey frequently or spend a lot of time in.

So, if we can’t keep watch over these remote areas of our seas and oceans, how then do we find out about the many unreachable, untraceable animals that live or pass through there? Simple – we ask the people who can.

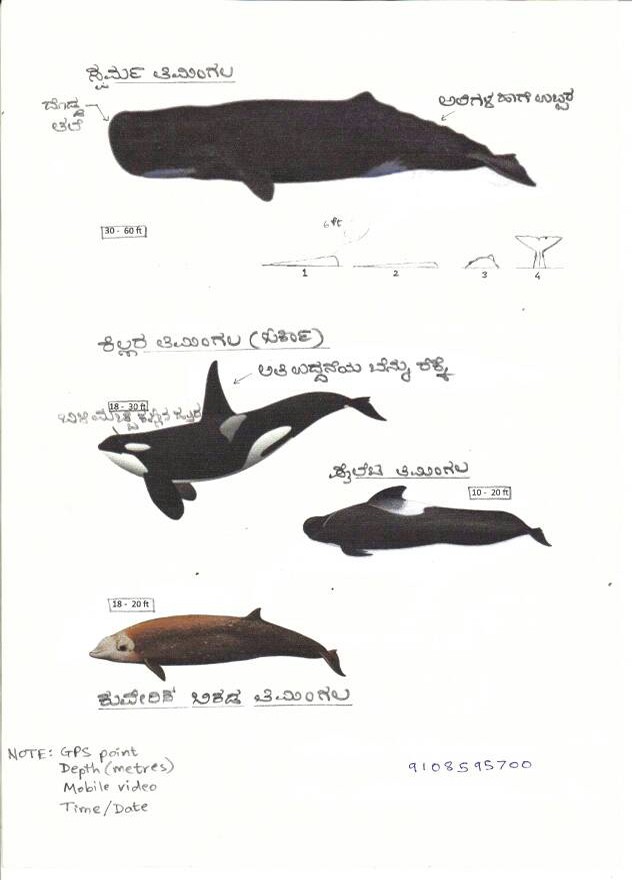

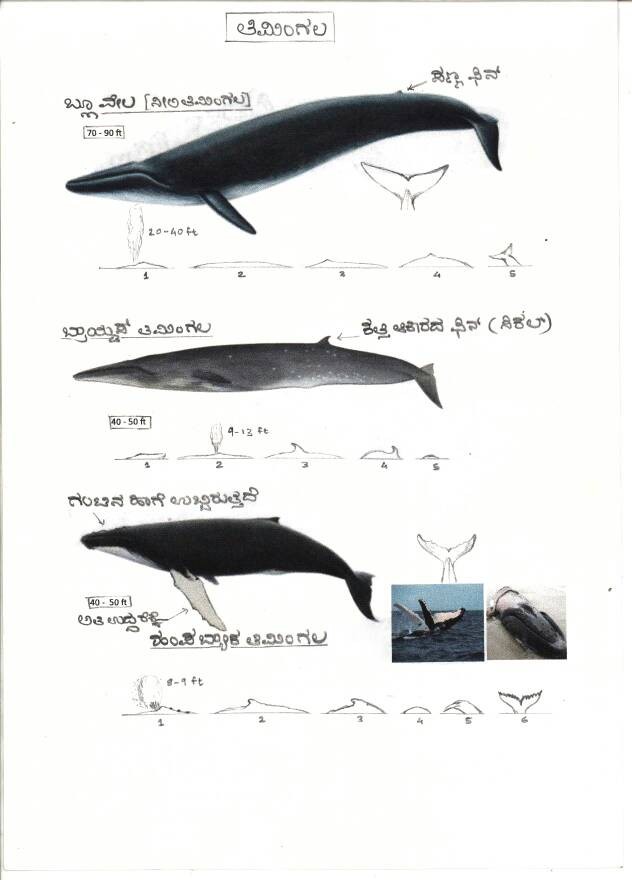

Alongside my own research studies, I began to delve into local, traditional knowledge whenever I was out on fieldwork. One of my favourite pastimes is to strike up conversations about marine mammals with locals wherever I go. I gather stories from most of them – some realistic (“Nustya savta sakalchaan ‘aaaa’ karun vair aaile” – in Konkani, a description of whales lunge-feeding on a fish shoal), and some bordering on the mythical (“Aisa hi tha lekin peeth par bada pankh tha” – someone pointing to a picture of a blue whale and insisting that it had an extra-long fin on its back). When I moved to Karwar in late 2015, I decided to go a step further. I started asking fishermen to tell me about their own sightings, as and when they happened. With the help of one of my marine biology teachers, I made Kannada language identification charts featuring marine mammals that could possibly be sighted in the region, and gave copies of these charts to some of the fishing crews who were keen to report sightings to me.

Soon, a number of fishermen started telling me about Baleen Whales, saying they abounded in the waters just a little farther offshore. Many of them claimed to see whales occasionally coming close to the coast as well. A few months prior to this, in the summer of 2015, the Konkan Cetacean Research Team working in Maharashtra had started seeing whales in coastal waters quite frequently, so this news from off the coast of Karwar got me very excited. I kept my fingers crossed for a sighting myself – to satisfy a personal longing to see a whale, and more importantly, to verify the claims of their being common in these parts.

On the more fantastic-sounding side of things, a few fishermen, mostly ones who had been working for decades, told me about dolphins that they sighted very rarely in distant offshore waters, in such huge groups that they churned the water from the boat all the way up to the horizon. Again, there was no proof of any of these sightings – not even rough records of date, time or location. There were well-documented records of dolphin ‘superpods’ (as these very large groups are informally called) on the east coast, where the sea gets very deep relatively close to shore, but none on the west coast. These fishermen weren’t confident about which kind of dolphins they had seen. One of them called them “speed dolphins”, but that was really nothing to go by. These stories may well have been true, but enchanting as they sounded, unearthing the details seemed like a reverie I had to let go of.

What was more of a letdown, however, was my lack of success in finding any information about my original quarry, the animal that had first fascinated me – the orca. Not a single fisherman I spoke to claimed to have seen an orca, even when I asked about them specifically. This seemed rather odd to me. Although orca sightings are far from common in these waters, I had expected that among hundreds of fisherfolk who spend at least three hundred days a year at sea, someone at least would have seen these animals.

There was one man who said he had seen orcas, but when I asked him where, he said “Discovery Channel.” A false alarm, and one of many jokes the locals so enjoy playing on me!

Then one day in November 2015, about two months after I had started talking to the fishermen in Karwar, I met a purse-seine fisherman named Om, who recognised the animal from the chart. He said he had had a good sighting of them very close to shore in South Goa. With a mix of excitement and some disbelief, I questioned his identification of the animals again and again (not that orcas have any real lookalikes). In response, he went on to narrate an astonishingly accurate account of the hunting behaviour he had once seen them engaged in. He was definitely talking about orcas. However, as a researcher, I cannot allow myself to actually log information without irrefutable proof, so I crossed my fingers and asked for photographic evidence. My heart instantly jumped when he said “yes” – and then just as quickly sank when he said he had lost the footage. “The hippies would have seen it and shot it too,” he said, (‘hippie’ being the colloquial term for any Westerner on a Goan beach). I wanted that video, but I had no idea where I could even begin searching for it. With a very heavy heart, I wrote this off as a ‘probable but unverified’ sighting.

A few weeks later, Om’s boat was set to leave for a five-day long offshore trip. The crew felt confident that they would run into whales, so they took me along. We were luckier than I had thought we would be. After four tiring days with not a splash in the water, we ran into a pod of over a hundred of those “speed dolphins”, which turned out, completely against my expectations, to be Arabian Common Dolphins – a species that is rarely recorded off the west coast. What I got was a very significant photographic record of this species for the region. But far more importantly for me, the sighting breathed new life into those fantastic stories I had heard from the senior fishermen. I had barely considered this species when I pictured those scenes they had narrated, but now it made perfect sense. Common Dolphins are highly gregarious, and their groups can easily number well into the hundreds, possibly over a thousand.

Sure enough, as the crew had predicted, we saw a pair of Bryde’s Whales on the fifth day. Based on that sighting where I was alongside the fishermen, I have been confident of the whale sightings they have been reporting to me ever since. Some accounts contain detailed behavioural records as well, ranging from vivid, animated narrations of the spectacular lunges these whales perform as they follow schools of fish to the surface, launching themselves out, jaws agape, to engulf the shoals, to narrations of rather less ‘impressive’ deeds, such as ejecting turbid clouds of poop right next to the boat, making it unbearable for the crew to breathe while the net was being hauled in. It has long been a dream to see the whales do those lunges (or maybe even to collect their poop, which would be as valuable as gold to a scientist) – but until that happens, detailed second-hand accounts from these seafarers will do.

Then, one day in late December 2015, when I was hopping off a boat after one of my daily surveys, a migrant labourer from another boat called out to me. When I walked up to him, I noticed that he was almost breathless with excitement.

“Why didn’t you come aboard our boat today? Why did you choose that one?” he asked.

“Because that was what had been planned,” I said. “Why?”

“Humne bada machhi dekha… Bhagwan machhi! Yahin paas mein, do thhe! “Woh bade, kaale… Jo khelte hain. Peeth par uncha pankh hai na, woh.” (“We saw whales! Two of them! Right here! Those big black playful ones with the tall dorsal fin.”)

It sounded like orcas. This boat was fishing only a couple of kilometres away from the one I was on.

If fate hadn’t driven my boat to chase a fish shoal at a different location that day, we could perhaps have been there at the right place. I knew a miss couldn’t get any narrower than this.

“Did you take videos?” I asked. “One of the other guys did. Come back tomorrow and check.”

The next day, I went straight to that boat. They took me out to the spot, but of course the animals were nowhere to be seen. Their accounts of the animals seemed to point to orcas, but precise descriptions varied, so there was no certainty about what species they were. I found the video that had been shot on a cell phone. There was a huge blackish marine mammal in it, moving swiftly and powerfully, but it was only a distant speck. It was a speck that no experts could identify either, other than calling it a blackfish (‘blackfish’ being the general term for the larger dolphins, all of which are dark in colour and have the word ‘whale’ in their names). And so, with mixed feelings about having an unusual animal on video but being unable to identify it, I logged this as “unidentified blackfish”.

Time went by. Bryde’s Whale records kept coming in, and I had another sighting of them myself, this time close to shore. One fisherman reported seeing blackfish-like animals again, but they swam away too quickly to be recorded. One more record of Common Dolphins came in from a crew that can reliably identify them – strengthening the notion that the species thought to be so rare here may not be rare after all. They may simply be under-recorded.

I continued to conduct my surveys with Om and his crewmates. One day, when I boarded the boat, Om told me to turn on my Bluetooth, scrolled through the picture gallery on his phone, and sent me something. I was stunned – it was the lost video he had told me about five months ago. It was eight minutes long – there were long gaps with nothing to see, but every half-minute or so was punctuated by a huge black fin slowly rising above the waves, with the shorter fin of a second animal close behind. They kept getting closer and closer, ultimately surfacing only a few metres ahead of the boat.

Black body, tall dorsal fins, white eyepatches – they were unmistakable. Orcas. Killer whales. Sea-pandas, if you will.

Going by the way they swam alongside the boat, heading north at such a steady speed, they seemed to be travelling through the area rather than actually spending time doing anything here. I could make out one of South Goa’s beaches in the background, and the hills of the Western Ghats. This wasn’t just the concrete proof I had been hoping for; it was also the most beautiful orca sighting I could have imagined. I was completely immersed in it – almost as if I were actually witnessing it myself.

By then, Om had become a trustworthy marine mammal informant. His enthusiasm seemed to inspire others around him as well. Records kept coming in. More fishermen actively began recording the data I was looking for: not just the animals they were seeing (identified to the best of their ability), but GPS coordinates and detailed behavioural observations too. And they continue to do so.

I am yet to see orcas myself. That narrowly missed sighting still bothers me a little. But a number of fishermen have seen and reported some very interesting sightings to me since then – two more orca records, a few records of large pods of dolphins, and a substantial number of Bryde’s Whale records.

For many reasons, a majority of the marine mammals on the west coast are still not easy to find, and one has to rely too much on being in the right place at the right time to observe them. But our waters are not out of reach for everyone. There are probably quite a few fishermen who have seen relatively rare or locally-undocumented animals, but haven’t reported them – or rather, haven’t had anyone asking them to report it.

For many of the fishermen I know (and indeed, for many fishermen all along our coast), whale sightings are commonplace. They simply hadn’t considered them worth noting until I told them I was interested.

My work is restricted to a very small area, yet there’s been a good amount of information revealed just from this region alone. The handful of dedicated marine mammal researchers across the country have also uncovered some remarkable details from the sea-going people in their regions. Still, marine mammal research in India is a field that’s only just catching on, and there are large gaps in our knowledge, waiting to be filled. Learning from local seafaring communities on a coast-wide scale and involving them in research might just take us far enough to start piecing together some of the seemingly huge puzzles about Indian marine mammals.

We may not have the thrill of spectacular sightings all to ourselves, but as long as someone is seeing them, as long as they’re being noted down instead of vaporising over time, it is, for all intents and purposes, thrilling enough.