A few years ago, when I was out snorkelling in the Andamans, I chanced upon what looked like a gloved hand underwater. Greyish in colour and fairly nondescript, I might have overlooked it altogether if it did not happen to be the only other thing in a landscape of sand. Closer inspection proved unhelpful, except to ascertain that this was some kind of organism. It was attached to the seafloor but swayed gently with the ebb and flow of the waves. It seemed to be covered in minute tentacles, which gave it a feathery appearance. An anemone shrimp perched on the organism eyed me with temerity as I mentally rifled through a list of sea creatures I did know, but I drew a blank. Later, on land, I would discover that I had been looking upon a species of leather coral (Lobophytum sp.), a type of soft coral.

When we think about corals and coral reefs, we often tend to think of the soft corals’ cousins, hard corals, and perhaps not without reason. Scleractinian hard corals, or stony corals, dominate our consciousness, fulfilling their role as reef builders with elan. Taking on a variety of growth forms, they endow tropical reefs with a semblance of structure, creating habitats for several different species of fish. This is made possible by the rigid calcium carbonate skeleton that hard corals possess, in a crystalline form known as aragonite. They are known as hermatypic, or reef-building corals.

On the other hand, soft corals are ahermatypic, meaning they do not contribute to the reef-building activity. They differ from hard corals in that they contain sclerites, which are minute calcareous needle-like elements. But recent research shows that they may have a more significant role to play in reef-building than earlier thought. Certain species of soft coral have been shown to cement their discrete sclerites into a more compact compound known as spiculite at their colony base which allows them to build reefs. Soft corals are colourful and varied but are often overshadowed by hard corals.

If we turn around and squint deeply into the past, the first appearance of soft corals on the scene is still murky. Early research showed that on the Geologic Time Scale (GTS), they were around at least from the Ordovician Period (~485.4 million years ago), although more recent research indicates that they may have existed even before that, from the Cambrian Period (~541 million years ago).

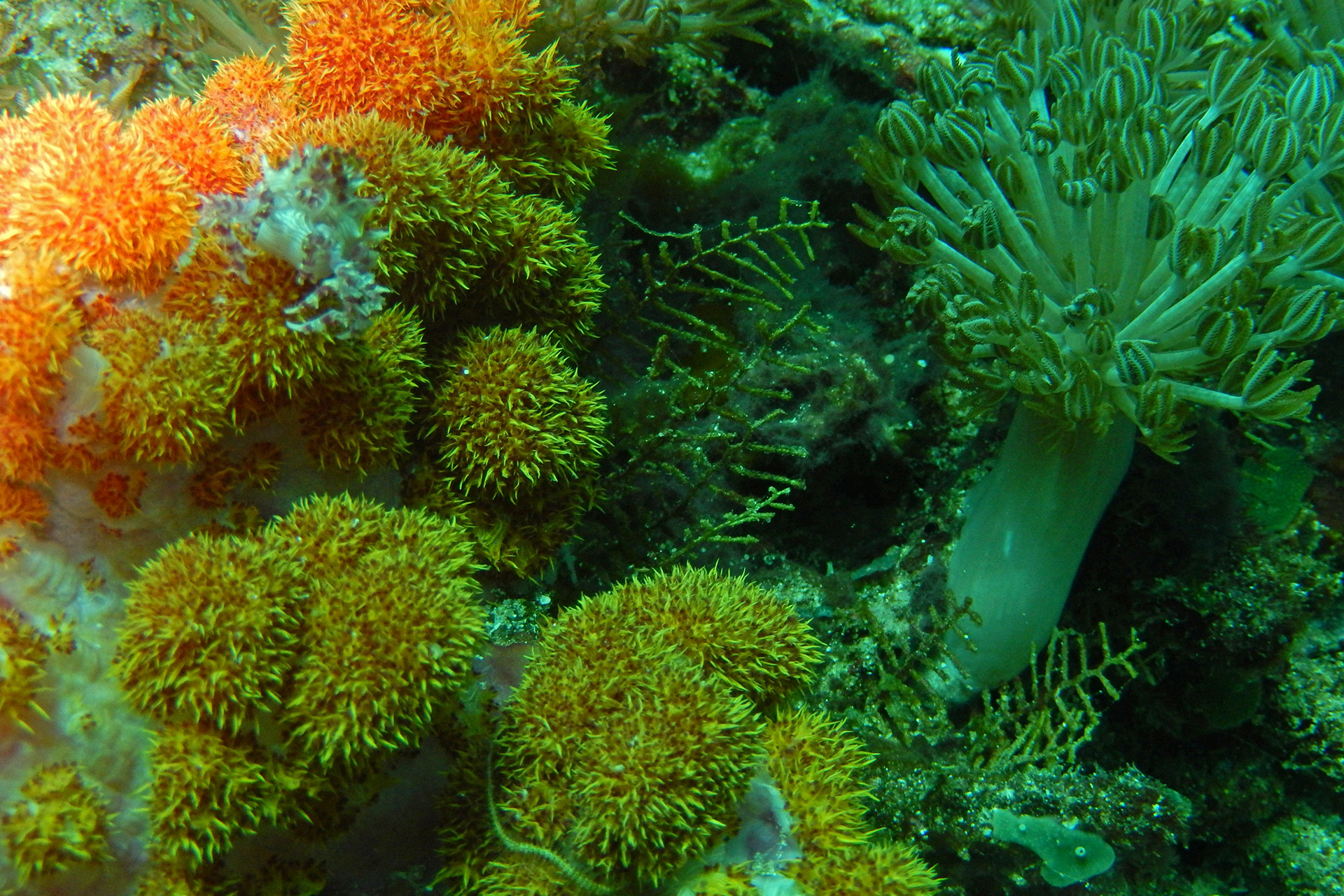

The soft coral I saw in the Andamans might have been the only colony in sight, but in other places several colonies may carpet the sea floor, forming a ‘garden’ of sorts, appearing as trees, bushes, fans, whips and grasses. These swathes of soft coral colonies are no less abuzz with life than hard coral colonies. Juvenile fish shimmer above these colonies, ready to dart to safety at a moment’s notice – on subsequent dives I have observed parrotfish, Moorish Idols, several butterflyfish and wrasse species, surgeonfish, unicornfish, and even juvenile snappers. Adult Honeycomb Groupers (Epinephelus merra) exude a sense of calm, fins splayed out against a soft coral colony, allowing curious divers to approach fairly close, before swimming away in a flash.

The colonies themselves ripple in an almost perpetually undulating motion. The energy requirement of some soft corals is met by their symbiotic association with zooxanthellae, a type of photosynthetic single-celled microorganism which also contributes to their colour. Others feed at night when individual polyps extend their eight tentacles to capture prey such as plankton from the water column. The eight-tentacle feature is unique to soft corals and distinguishes them from their hard coral cousins, whose polyps have multiples of six tentacles.

I am perhaps wiser to their existence now than I was a few years ago, but there is much that is yet to be learnt about these fascinating organisms. On a dive earlier this year, a crinoid, or feather star, detached itself from a massive Gorgonian (a kind of soft coral) and did its peculiar step-swim away into the blue, while the coral ‘looked on’, as I am sure its ancestor must have done so many millions of years ago. There was not a single hard coral colony in sight, but everywhere I looked, soft corals swayed as if to some unheard music, perhaps to the deep harmony of the ocean asserting them into existence.