A little ahead, I saw half a pugmark on the leaf-littered trail; revealing sure enough that it was a tiger (Panthera tigris). We waited for a few minutes and scanned the bush, but there was no sign of the cryptic felid. But I knew, perhaps by primeval instinct, that a cat was nearby, hiding, watching and waiting, as these ambush predators have evolved to do. Just this time we weren’t its natural prey; we were an intrusion.

That was in February 2016. But it was in 2010, on an erstwhile hunting road dominated by Pandanus and thick semi-evergreen forest, where I first saw tiger pugmarks in the Sahyadris – as the Western Ghats are known in their northern ranges. I was surveying a landscape spanning 5000 square-km in the region to assess the distribution of large carnivores, which also included the Dhole (Cuon alpinus), leopard (Panthera pardus) and Sloth Bear (Melursus ursinus) that co-occur with the tiger. Through my research, I also assessed landscape connectivity and habitat-use of these four large predators. All four large carnivores are threatened, with the tiger and Dhole being far more susceptible to local extinction because of habitat fragmentation and prey depletion in the ‘Sahyadri corridor’.

Corridors are the last tracts of remaining natural habitat which are essential to keep protected areas from becoming isolated for terrestrial wild mammals in a sea of humanity, i.e. human-induced land-use change. The importance of corridors for the persistence and genetic diversity of large mammals is now being understood by scientists, and efforts have begun in India to declare wildlife corridors, so that commercial development and land-use change can be restricted in these areas. My research portends a grim future if governments pursue the ‘business as usual’ approach. The Sahyadri corridor is severely threatened by linear intrusions (roads, railway lines), hill-station development, wind farms, and mining, and this is the last stand for the charismatic tiger in its northern range limits in the Western Ghats. If we don’t act now, the species and many natural habitats will vanish, forever.

The Sahyadri corridor

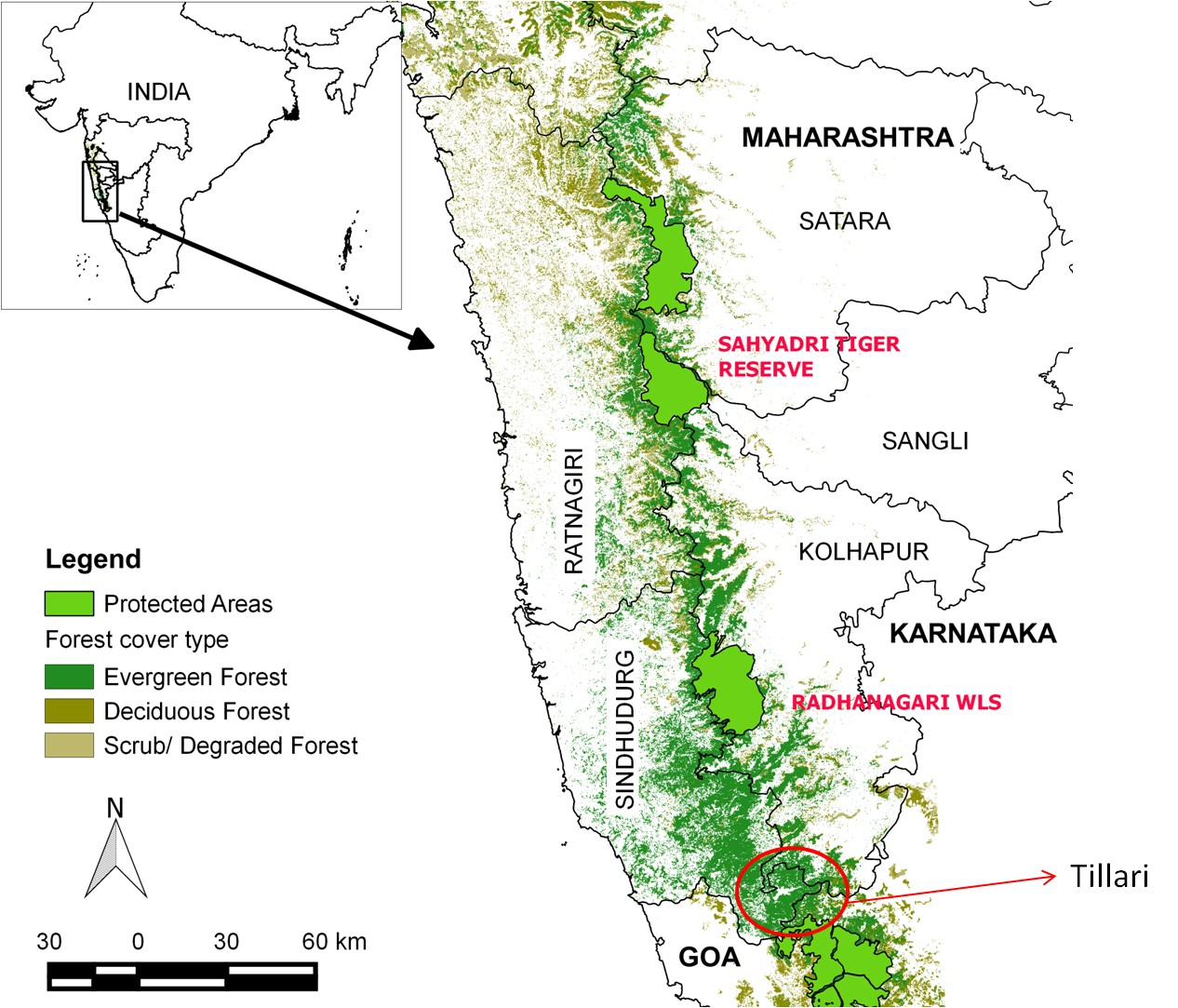

The region where I have conducted my research spans from the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve in the north, which comprises of Koyna Wildlife Sanctuary and Chandoli National Park, and stretches to the Tillari region in southernmost Maharashtra. The Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary, famous for gaur (Bos gaurus), lies halfway between Sahyadri Tiger Reserve and Tillari, and is a cosmic mix of moist deciduous and semi-evergreen forest. Although there are no estimates of tiger density currently, the Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary has a sufficiently large continuous habitat (350square-km), with good potential for recovery of tigers if well-protected. Tillari, which is located at the southern tip of Maharashtra, is vital to make this happen, as it lies connected to Mhadei Wildlife Sanctuary in Goa and Bhimgad in Karnataka, with a breeding population of tigers in all three regions. The corridor, which comprises of patches of Reserved Forests and private forests, connects these protected areas and is vital remnant habitat for a suite of large mammalian wildlife and biodiversity.

Tillari supports a fair density of large herbivores, and together with Mhadei and Bhimgad, forms a habitat that’s important for conservation of tigers. Tillari also has a small resident population of elephants, but they are the cause of much antipathy given their disposition to raid cash crops and their tendency to retaliate when driven away by irate farmers. However, improved management and conservation actions can reduce these conflicts and large mammals can continue to persist if timely steps are taken.

‘Coexistence is a journey, not a destination’, I often remind myself when cynicism takes over.

Coexistence would require introducing innovative measures for crop protection, such as erecting chilli fences, trip alarms, and electric-fencing around croplands, meanwhile shifting local livelihoods and economies to more environment-friendly sources of income such as ecotourism to replace intensive cash crop cultivation. Although not a silver bullet, well-managed ecotourism can change people’s attitudes towards large wildlife in human-dominated landscapes. Once protection and management improves, recovery of large herbivore prey will help in increasing tiger densities, which can eventually help resurrect Radhanagari and even Sahyadri Tiger Reserve.

Keeping a corridor intact

By using concepts from physics, such as current flow and resistance, scientific models help researchers assess connectivity to understand how animals would move through a landscape. An area where tigers are breeding and their population is growing would be able to support only a certain number of individuals, given limitations of habitat and prey. Therefore, young tigers usually tend to disperse into adjoining habitats where they may reside or disperse farther, based on a number of factors which include prey density, human disturbance and the degree of favourable habitat for residence or movement. Tigers have been known to make long-range dispersals between protected areas, sometimes even a whopping 650 km. Such movements may be seasonal, or sometimes even take place over generations – many of these intriguing facts we are just about starting to unravel. Similarly, other large carnivores also move and disperse based on area-range requirements.

From my research, I have found that landscape connectivity is threatened for all four large carnivores in the Sahyadri corridor, and it is more severe for the larger-bodied tiger and Sloth Bear, than for the Dhole or leopard. For instance, if a dispersing tiger were to travel from Mhadei Wildlife Sanctuary to Sahyadri Tiger Reserve, it faces ten times more ‘resistance’ (or obstruction) than it would to travel to Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary, which is located midway. This is mainly because the corridor north of Radhangari Wildlife Sanctuary to Sahyadri Tiger Reserve is broken and tenuous in most parts; so resistance to movement is high. This resistance to movement results from a number of factors such as distance between PAs, degree of habitat contiguity, terrain, density of human settlements, and edge effects due to roads, among others. Interestingly, the magnitude of resistance faced varies according to the species. A leopard would face only half the resistance than a tiger would to disperse between these Protected Areas.

This can possibly be attributed to the leopard having a much smaller body-size, and its greater adaptability to human-induced changes and disturbances in natural habitats. Therefore, it appears that maintaining connectivity is much more important for larger-bodied carnivores to persist in this landscape.

While this finding is nothing novel, achieving this mammoth conservation task requires a whole lot of commitment from various actors. In this age of thoughtless consumerism and blind anthropocentrism, this is an intricate conservation problem. Vote-hungry politicians, a disillusioned forest service, and economic growth-centric narratives make rejections of ‘development’ projects near impossible. There are a number of new road projects coming up in this landscape. For example, a proposed SH 120 and 121 passing through Shivdav-Ghotge villages will cut through an important patch of corridor that connects Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary to the Reserved Forests of Patgaon-Ajara-Amboli region.

There is never any consideration given to whether such roads are actually necessary, even though governments can barely maintain roads that already exist and cut through our forests. What we are left with are half-baked ‘mitigation’ measures (such as underpasses, bridges, culverts, and passages) which do little, other than add salt to an already wounded and disheartened conservation lobby. This is not to say that mitigation measures are not necessary, but they are secondary when one could avoid building a road altogether.

Conservationists often appear gloomy to many people, but this is not because we are perpetually depressed, but because we suffer from an excessive passion for wildlife and wild places, and care deeply about them. Look at a conservationist in in the lap of nature and one will see a transformed being, like a newly-emerged butterfly, or a gleaming new leaf. Encounters with wildlife have been one of the most invigorating moments in my professional life, especially since wildlife is very cryptic where I’ve worked, and sightings are few and far between. My first sighting of adult dhole in Tillari came after three years of working in the region, though signs of them were commonly encountered. And when I saw dholes, I saw them in all their vivacity, chasing an adult sambar and taking quick bites at its side on a deserted road through the forest. On seeing me, the sambar scurried up a very steep slope into oblivion. The dholes were a little bothered as I had turned up unexpectedly, but quickly got back to chasing their quarry. They momentarily moved away from the sambar, but being as quick-footed as their prey, they clambered up a very steep rocky precipice to follow it. I couldn’t believe my eyes – I had just seen dholes climb an almost vertical mountain slope! I stepped out from my vehicle and waited for a lot of time, hoping to see or hear something more. But I could only hear the cacophony of langurs sitting high up in the canopy, looking at this spectacular interaction between predator and prey. Eventually the calls faded, just like the evening light, and I went along my way, away from this magical forest

A conservation blueprint

So how can conservation work in this landscape? Similar to most other places, the Sahyadri corridor is plagued with immense challenges. The most critical is the lack of any legal recognition of this corridor, which is otherwise just Reserved Forest. Although this has started to change. Some corridors have been included in the Tiger Conservation Plans (TCPs) of Tiger Reserves, which give them some legal protection, but more areas need to be added to secure remnant habitats within larger Tiger Conservation Landscapes. Illegal hunting is also widespread in this region, and competition that local people create by hunting and grazing livestock in Reserved Forests severely affects wild ungulates and carnivores. High densities of free-grazing livestock in forests compete for forage with large herbivores, usually resulting in the space being avoided by wild ungulates, while hunting severely depletes prey densities for large carnivores.

Conservation can work through a landscape conservation strategy to improve management of protected areas, maintain connectivity in the landscape by reducing habitat fragmentation, and improve management of Reserved Forests in the corridors. This is by no means possible unless there is widespread support to conserve these iconic species, especially by politicians and forest departments, but also by civil society. Conservationists are working tirelessly to make positive changes so that we can cherish wildlife for a long time to come. Tigers can continue to survive in the Sahyadris, but we need to fulfil our commitments to keep these places wild.