Twelve years ago, on the 26th of July, a cloudburst showered the city of Mumbai with about 900 mm of rain in a single day. Over 1,200 people died in that deluge of 2005. There was grief and anger all around. It was vowed that the city would never ever be devastated like this again, and that improvements would be made to the infrastructure. Thousands of crores of taxpayers’ money were spent, and every year, we heard boastful announcements that the city is rain-ready.

Is it? The answer is a resounding NO. The eyeopener came just one month ago, in the form of about 350mm of rain on the 29th of August. Just a fraction of what inundated the city in 2005, but enough to make all hell broke loose yet again. Just take a look at these photographs from the recent floods in Mumbai.

It rained again, heavily, in September. But… a coastal city in India is supposed to get heavy rains, isn’t it? Why are we complaining, you ask?

There’s nothing wrong with the rain, but there’s surely something wrong with the way the city of Mumbai is evolving geographically. There are many factors to Mumbai’s vulnerability to floods; the loss of its mangroves is foremost among them.

The dense forests between much of Mumbai’s coastline and the Arabian sea are almost completely submerged at high tide. These mangrove trees with their aerial roots are integral to the health of this intertidal habitat, and the low-lying coastal city they abut.

They act as a natural barrier against floods, protect the shoreline from erosion, and curb the ingress of salinity, so harmful to fertile soil further inland. They are rich in biodiversity – and provide a home to several animal, plant and marine species. Mangroves are also crucial in our fight against climate change: they absorb almost eight times more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than any other ecosystem.

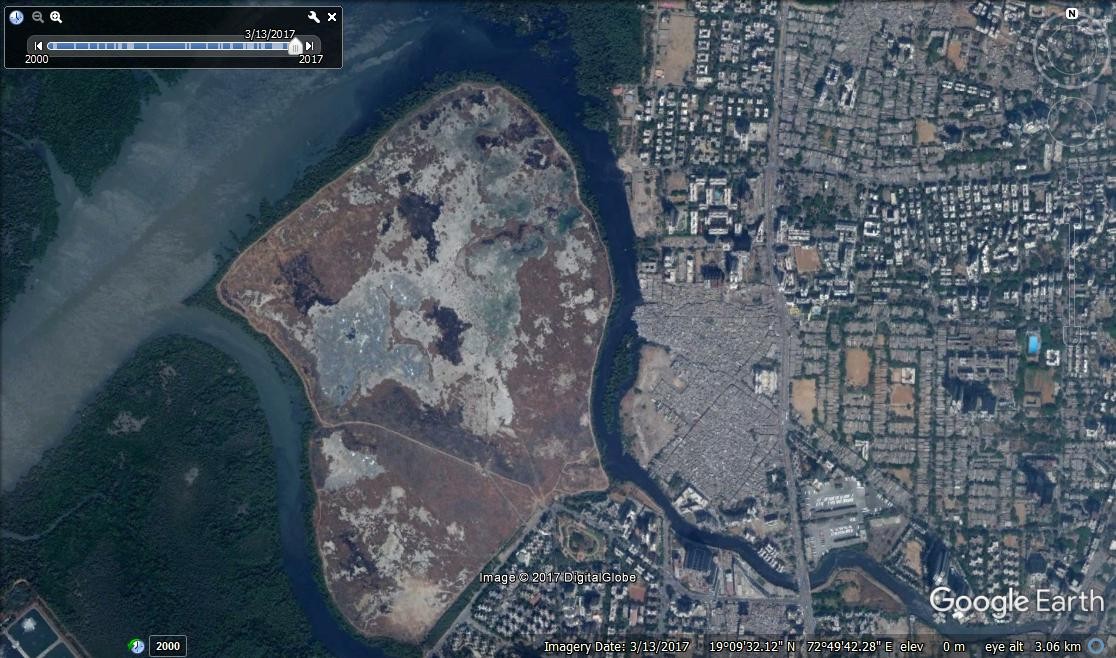

Let us take a look at the state of the mangroves in Mumbai. The city has around 40sqkm of mangrove forest – by most estimates, this is only about 30 per cent of what once existed. A spate of land reclamation and development projects have eaten into these forests, and with them, the city’s resilience to extreme weather events.

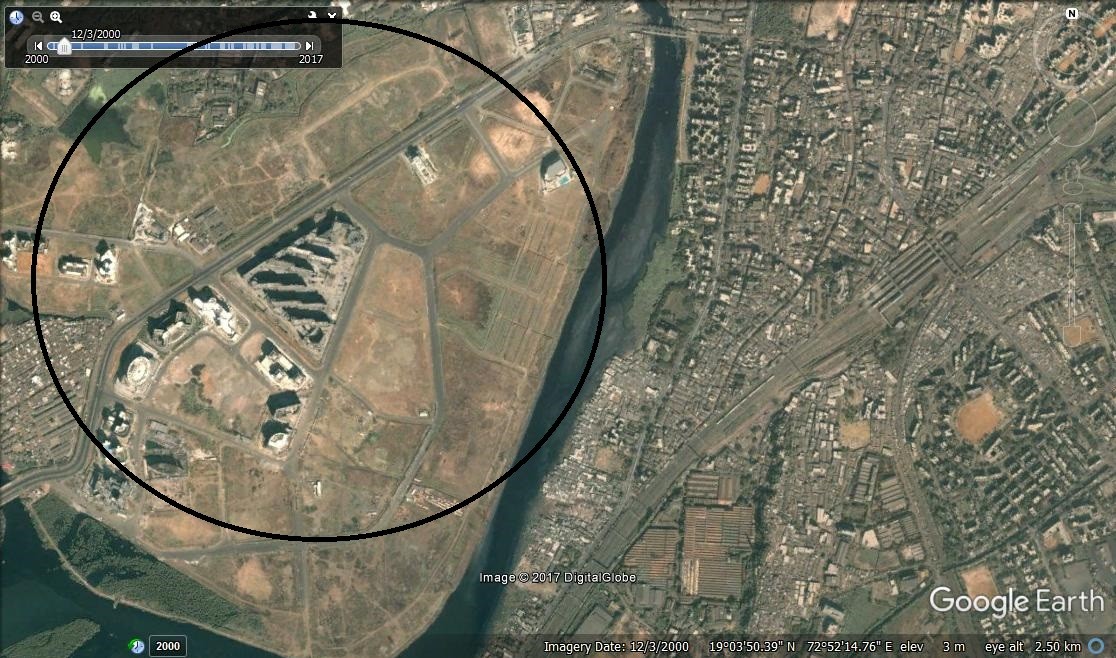

The Mithi river, Oshiwara river, and Thane creek – all dense with mangroves, are dispersal zones for flood waters. The Mithi river got its name from the quality of water, which used to be sweet, once upon a time not too long ago. It regularly romanced the sea through the mangroves in its estuary from Vakola to Mahim Causeway. One fine day, the powers that rule decided that the Mithi estuary, teeming with mangroves, was the best place to make a business hub. And before environmentalists could do anything about it, the entire mangrove belt of about 350 acres was dumped with everything from debris to mud to waste. BKC, or the Bandra Kurla Complex was born on the river’s floodplains. This was probably one of the largest ecological sites to ever be destroyed by a government agency in India. It is no secret that those devastating floods of 2005 were caused in part because the Mithi’s natural drainage system had been blocked by this project.

But now, that record will be beaten by a huge margin by the City and Industrial Development Corporation of Maharashtra (CIDCO) if and when it constructs the Navi Mumbai airport.

Ironically, it will be called the “Green Field Airport” which, if you ask me, is adding insult to injury. Building that airport involves diverting two rivers, reclaiming a thousand acres or more of mudflats, destroying around 400 acres of mangroves, blasting and levelling two hills, and displacing nearly a dozen villages that are self-sufficient in fishing and farming. What is green about it?

The story is a similar one everywhere you look. Today, the Oshiwara river fares no better. Over 300 acres of pristine mangrove lands with mudflats in it has been being reclaimed steadily for more than a decade. Many complaints have been lodged but the state continues to snore away in deep feigned ignorance.

But Mumbai finally has a saviour in the form of the Mangrove Cell of the Maharashtra State Forest Department. It was created in 2012 to protect, conserve and manage the mangroves and coastal biodiversity of the state. To a large extent, it has been able to stem the rot due to dumping and reclamation. Non-governmental organisations and environmental groups like Vanashakti are also involved in the restoration of degraded mangrove areas.

We conveniently forget that nature decides when it is payback time for the unsustainable course we took. In the case of Mumbai, it is many years after much of the destruction of its mangroves took place. But now that the damage is already done, the city will be brought to its knees every time it rains more than 100mm in one day.

Millions of litres of floodwater are soaked in and held by the mangrove wetlands.. Tampering with them has had massive repercussions which will only worsen in the future. That is the price to be paid for development at the cost of natural shields and sponges like mangroves. The romance between the river and sea in mangrove land must never be compromised. Any change in the interface can mean only one thing for humans: misery.