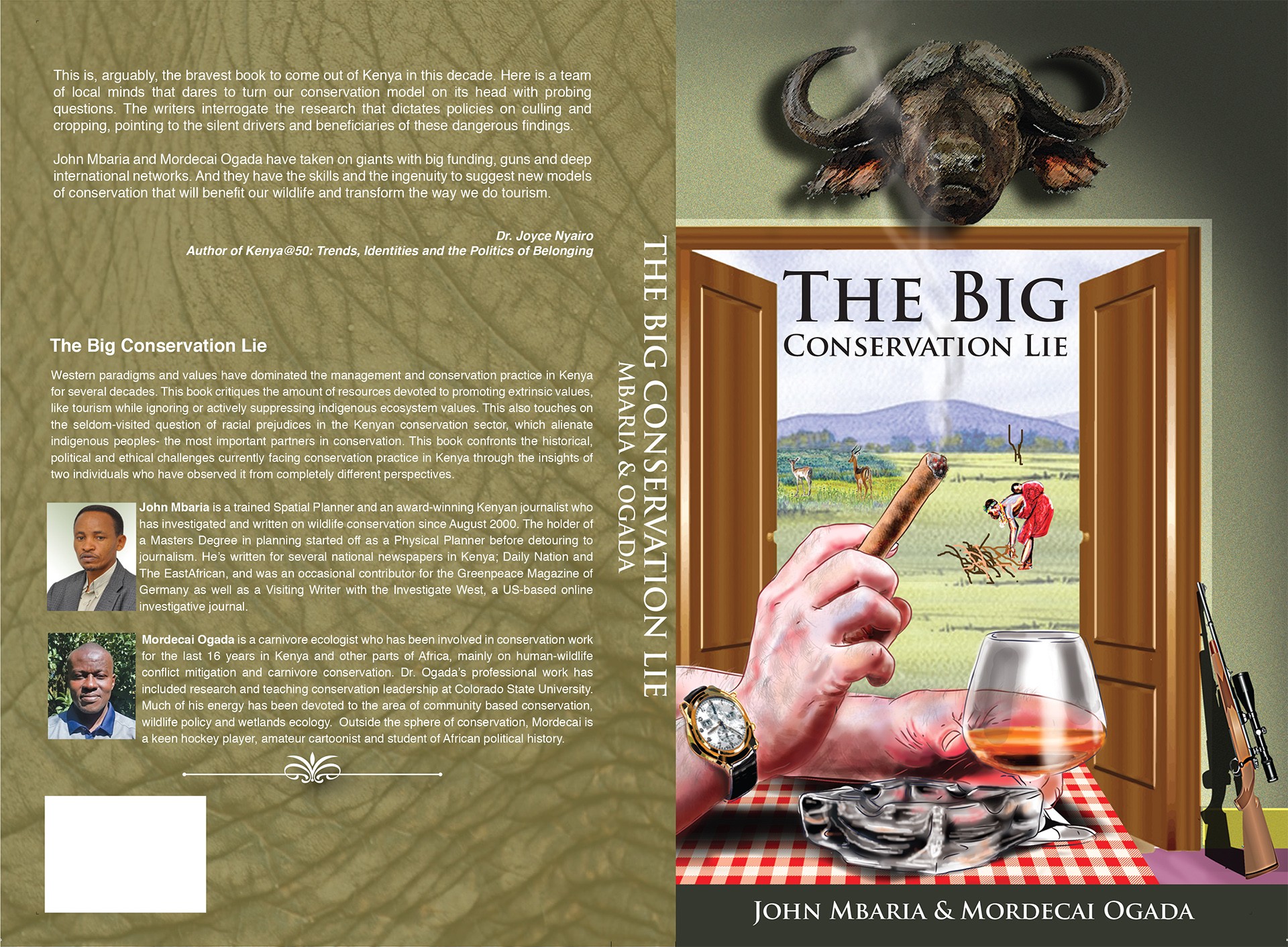

A carnivore ecologist from Kenya, Mordecai Ogada is a fierce critic of the dominant conservation practices in Africa today. In a continent where indigenous people who hunt for bush meat are often vilified as poachers while foreign sport hunters are celebrated as heroes, his book, The Big Conservation Lie – co-authored with John Mbaria – is a ruthless exposé of a system that perpetuates class and racial prejudices better than it protects wildlife.

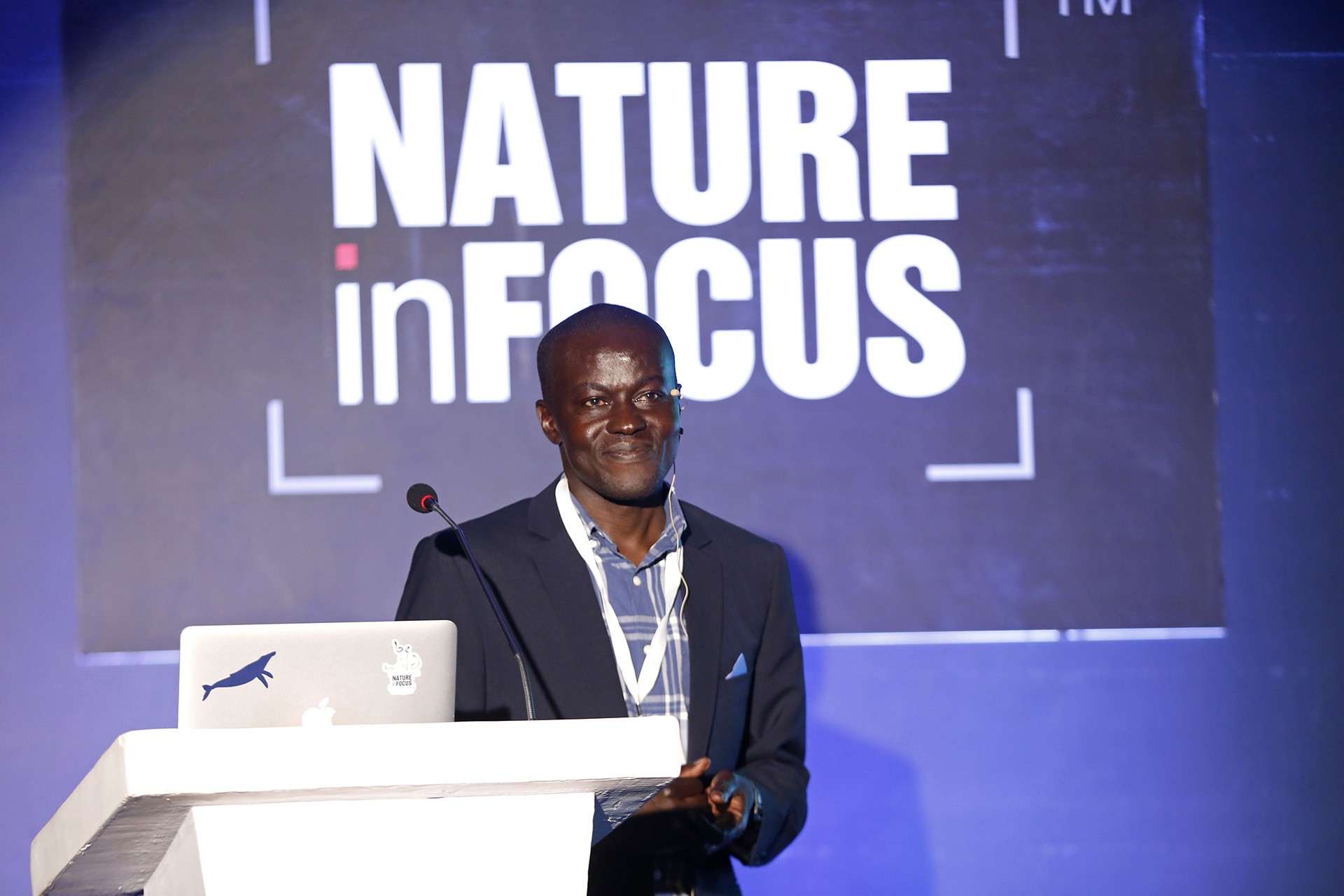

Ogada was a keynote speaker at this year’s Nature inFocus Photography Festival. Here, he talks about how the ecology of the future has to focus more on coexistence and less on conflict, and explains how Western interests from a colonial past continue to warp the conservation industry in Africa today. Read on.

What does it mean to be a carnivore ecologist today?

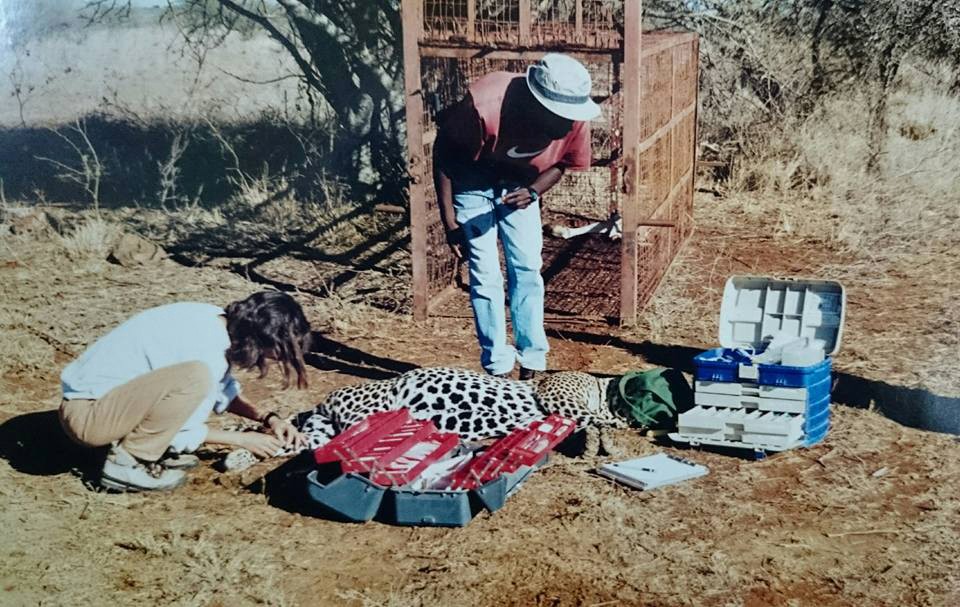

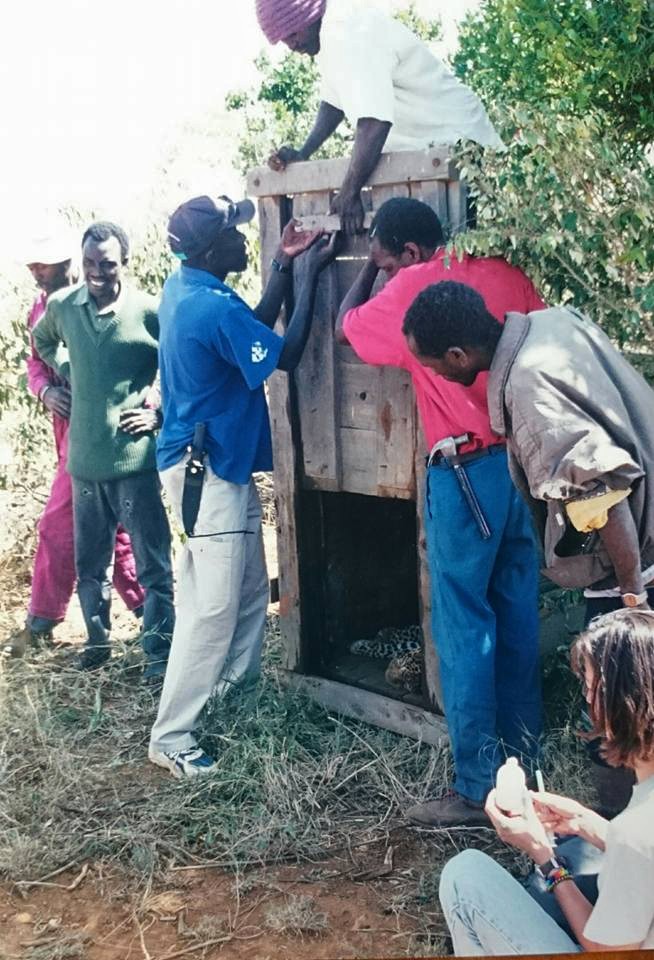

To me, carnivore ecology means understanding how we can live together with carnivores sustainably, how we can minimise the losses of livestock to carnivores. The future of conservation is not in separation, or in establishing national parks – that idea is obsolete – but in creating our own niches and coexisting. That’s why it’s fascinating to me when I read about leopards in India, living in cities and in villages. That is the frontier of ecology. Ecology today has to be about how they live with us and how we live with them.

It’s a tragedy that scientists with PhDs are presented with conservation problems and they come up with solutions like ‘let’s build a fence.’ That was innovative back for the Great Wall of China, for Hadrian’s Wall….We can’t be coming up with that in 2017.

You have been a vocal opponent of fencing, and of creating boundaries as a way to save our wildlife. For those who might be on the fence about it, could you explain why fences are part of the problem, rather than a solution?

Wherever you go in the world, fences are not just physical barriers, they are cultural, psychological barriers – the world is full of fences that have cost millions in terms of money and lives, but are still not doing their job.

There has to be connectivity between natural areas, not separation. Really, it’s not about the size but the corridors. If you had three forests of 100 acres each and they were connected, that is more useful than one forest of 500 acres. This is especially true for carnivore societies, which are strongly territorial. Each lion needs to find its own place, or it will be killed by the resident pride.

And in many parts of Africa, conservation goes along with controlling lands in one way or another. Look at the hirola antelope, a highly endangered animal restricted to eastern Kenya. An NGO has gone and fenced in much of the remaining population, to “protect it from predators”. But by doing that, they’ve fenced in the dollars as well. Any donor funds that go toward hirola conservation will now go to them. And when you restrict a wild population like that, diseases get amplified, parasite loads increase. It is amazing to see the negative impacts of fences in wild landscapes. More often than not, it’s little to do with conservation, more to do with material gains.

You’ve spoken about how wildlife tourism in Kenya, and other parts of Africa, has cemented inequality and racial prejudice in a way that is rarely acknowledged. Tell us more.

In Kenya, wildlife management structures and organisations were created by British colonial authorities. They were set up to guard, not to think about policy or research. There’s no organisation here like the Wildlife Institute of India, for instance, which sets the research agenda. For us, it’s driven by NGOs, which is a problem. We need to set our own wildlife agenda.

Right now, everything is driven by external needs: some foreigner wants to hunt our animals, so we decide to encourage sport hunting. We arrest our villagers for eating wild animals because someone from the outside told us it is cruel. We move pastoralists out of their homes so foreigners can come and watch wildlife. In my experience, Kenya is the only place where people can come to Samburu, but don’t want to see any Samburu people. And let’s not be fooled. Tourism dollars go to the hotel, not to the people. In northern Kenya, tourism has been a creator of poverty.

But the most amazing thing to me is how this is going on and everyone knows it is wrong but no one is talking about it. When enough people are speaking about it, then we can see what we want to do about it.

In your keynote presentation at the Nature inFocus festival in August this year, you made a very thought-provoking statement – we don’t see many black faces in conservation in Africa. It’s true, and we’re all guilty of not realising this earlier. Why is the situation the way it is today?

Look at old photographs or movies: the hunters were white, the gunbearers or trackers were black. Today in Africa, the scientist or explorer or photographer is white, the assistant or guide is black.

Our conservation model is top down, imposed from the outside. It is not inspired by traditional culture or values. And it is completely donor funded; donor funds are finite.

In fact, because it is not a locally run movement, conservation work in Africa is geared towards getting donor funds or tourism, not towards protecting wildlife. For instance look at this trend of vulture restaurants. That’s a real problem. Habituating vultures to artificial feeding is nonsense – you’re going have a whole generation of vultures that don’t know how to find food on their own. Don’t tell me it’s supplemental food for them, either. A wild animal isn’t going to go out hunting for hundreds of miles when it knows tomorrow morning there’ll be food right here.

There was an effort since 2004 to get community conservation up and running in Africa, but now, all those organisations are headed by white people! Africans have to tell their story on their own – whether it’s about health, governance, food security or conservation – not through the prism of Western eyes.

Indigenous people everywhere – be they forest dwelling tribes or nomadic pastoralists – are the most important partners in conservation, but in most countries, they have been systematically excluded from conservation efforts. You’ve said that much of the conservation work in Africa has been little more than a land grab that disregards local communities. Could you explain?

In Africa, indigenous communities are framed as part of the problem, not the solution. Rangelands have become militarised areas to keep the local people out. We burn down villages to create hunting blocks.

Local people have been accused of everything from over-grazing their herds on the grasslands to poaching wildlife. There are a lot of exaggerations and falsifications in the poaching story – in Kenya, the poaching of elephants is now a non-issue, but there’s a need to maintain the crisis to maintain the funds. And when it comes to grazing, by concentrating herds in smaller areas, you’re actually creating a problem where there wasn’t one. Pastoralists have been pushed to the peripheral, less productive areas of their ancestral lands, while the lands with forests and springs have been set aside for tourists. So in the dry season, naturally, there is conflict over resources, and this often becomes violent. It is the tourism product that is the problem, not the herds or the local people. After all, for generations we’ve lived freely with wild animals and protected the environment.

The thing is you have always had elephants and rhinos and lions and cattle and people using the same land. They are not mutually exclusive, they do it perfectly well together. The livestock actually protects the health of the rangelands. The elephant has no problem with the cows, but the tourism industry does. Tourism here is selling a wilderness product, as if there are no people here, no livestock here. But it’s artificial; wilderness doesn’t exist like that in Africa.

If indigenous communities aren’t being vilified, they’re being made the subjects of some global pity party: “oh”, they say, “the local people need help managing their resources, so we must go in and help them”.

Two of the most controversial conservation issues in Africa today are the culling of wild animals, and sport hunting. Could you share your insights on these with us?

A few years ago, some private landowners got licenses to do what they called cropping, or culling of zebras on their land – they sell the hides to markets in southern Africa and make money off wildlife.

In Kenya, these things are biased to benefit a certain class of landowner. It only benefits those who have license for firearms, and access to other countries, which are the markets for these wildlife products. Still, it’s restricted to “problem animals” as of now.

When it comes to sport hunting, which is rampant everywhere south of Kenya, the problem is it is organised by foreigners, managed by foreigners, patronised by foreigners. It’s a myth that the money is funnelled back into the community; mostly the benefits go directly to the safari outfitters (with the exception of some community-run conservancies in Namibia).

In any case, it’s not a management tool, the way most people would have you believe. Managing wildlife populations by culling or hunting is a complete lie. Nature regulates itself – a carnivore that gets old gets fought by a younger one or dies because it can’t hunt anymore, you don’t need a hunter to come and kill it. An impala or buffalo gets old, and a hyena comes to get it, you don’t need a hunter to take it out. These are myths to justify sport hunting.

Clearly, hunting in Africa is not all about sport or wildlife – it is about expressing dominance over the land and the people where you’re hunting. Why else would a bush meat hunter, be called a criminal, while the sport hunter is celebrated as a hero? We’ve banned traditional hunter-gatherers from their way of life to make way for this industry. Which one is more sustainable?