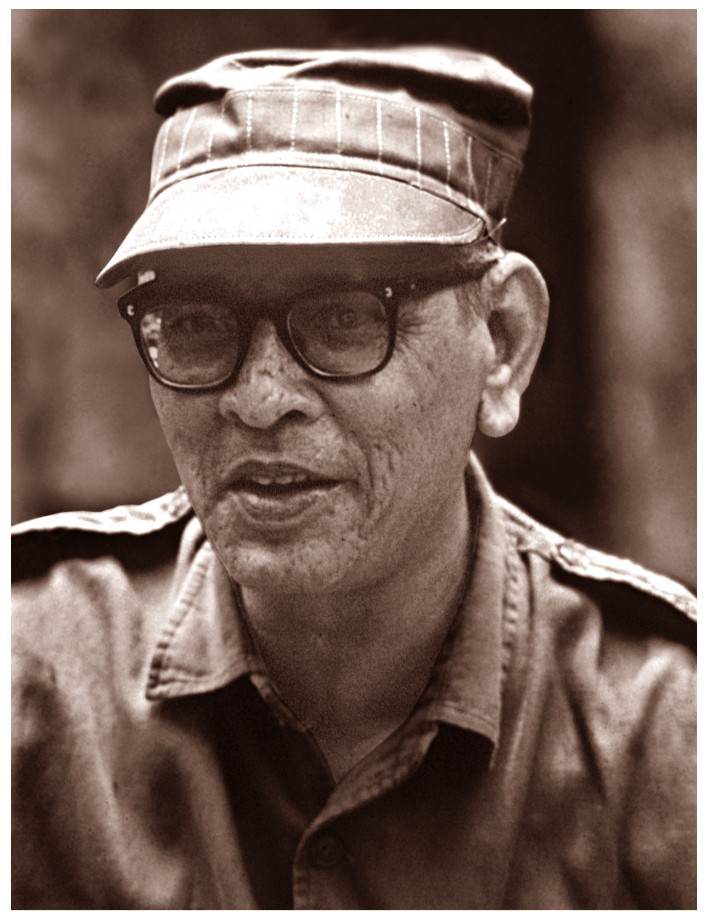

I was always in awe of M. Krishnan, in part because his reputation preceded him and partly because he was never an effusive man. Long before I met him I would devour his ‘Country Notebook’ column, which he wrote for The Statesman of Calcutta for 45 straight years from the 1950s onward. When I finally had the chance to meet him I felt I was intruding on a genius. It took a trip to Ranthambhore in early 1981, when he and I stayed at Jogi Mahal, on invitation from Fateh Singh Rathore, then the Field Director of the Park, to set me at ease.

I was sitting on the verandah of Jogi Mahal, my usual breakfast spot after a forest round, and had 40 or 50 of my photographs spread out before me as I alternately scanned the lake shore for wild creatures and skimmed through the images to separate the wheat from the chaff. To my surprise and delight, behind my cane chair, stood the great M. Krishnan, cup of tea in hand. “I think the best one you have in that lot is the backlit one of the young monkey hanging to the tail of the other to reach up to grab the banyan tree branch.”

I used to make copious notes back then, and reading my old diaries here is what I found written decades ago about that day.

Always economical with words, Krishnan said: “One in 50 is not a bad average. You should try shooting in black and white.” He then proceeded to ignore me for the next couple of hours as he sat, writing notes, checking equipment and generally making sure I did not breach the wall of isolation he created around himself. He had an eye for the image. The one he selected was used by me to launch Sanctuary Asia a few months later and down the years, in his unique, minimalistic way he helped the magazine to set the bar for content, including texts and photographs.

I felt blessed to have his attention. I was a rookie, yet I had the temerity to imagine I could launch a wildlife magazine. I wondered why he took time out to pass on such valuable advice to a total stranger. It could have been something in my enthusiastic sincerity. Possibly Fateh Singh might have spoken to him about me. This I know… the moment the legendary Krishnan heard of my plan to start a serious photography and science-based wildlife magazine he (thank my lucky stars) decided to take me under his wing for a couple of years.

To get some idea of the Krishnan-filter I had to pass through and the straight-talk I heard from him as he shaped my attitudes quietly but firmly, consider this quote from the great man:

The average educated adult knows little or nothing of the teeming plant and animal life of the country, and cares less. Livestock does not interest him, and the world is to him a place which holds only human beings. He can never make friends with a hill or a dog, and if he has no one to talk to, no book to read, and no gadget to turn and unturn, he is quite lost. School education is solidly to blame for all this.

Born in Tirunelveli, M. Krishnan was a product of the Hindu High School and Presidency College. Not best known for his academic brilliance, he nevertheless notched up a BA and a law degree, but eventually carved a secure niche for himself where his heart took him – as a freelance writer and artist. A keen naturalist, Krishnan had a more than casual interest in botany, mastered over the course of several field visits to the Nilgiri Hills in the company of a scientist called Professor P.F. Fyson. After running through several jobs, none of which really interested him (Public Relations Officer for All India Radio, Political Secretary to the Maharaja of Sandur!), he honed in on a writing career that was to span several decades. Recognising his immense potential, the Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund awarded Krishnan a Fellowship in the mid-1960s for an ecological survey of the mammals of peninsular India.

A prolific writer, it remains a mystery why publishers did not mob him for texts to publish. It beggars belief that only two of his collections were published in his lifetime – Jungle and Backyard and Nights and Days. People who read Tamil say he wrote best in his native language. I considered it a great loss that Tamil was not a language I knew, judging from his flow in English:

Inside the compartment it was crowded and close, and outside too the afternoon was muggy. I bought a ‘sweet-lime’ at Jalarpet Junction to assuage thirst and lassitude, and balanced it speculatively on my bent knee. Would it be bitter, would it be weak and watery, or would it be sharply satisfying? A hairy grey arm slid over my shoulder, lifted the fruit off my knees, and disappeared, all in one slick, unerring movement. I jumped out of the compartment, and there, perched on the roof of the carriage, was the new owner of the sweet-lime – a trim, pink-and-grey she-monkey, eating it. (Monkey Versus Man, Nature’s Spokesman, M. Krishnan, Oxford, Edited by Ramchandra Guha)

In the event, after that fateful trip to Ranthambhore at the behest of Fateh Singh Rathore, M. Krishnan agreed to write for Sanctuary Asia. Neither of these greats are with us today, but I will always owe them both a debt of gratitude for helping shape the magazine that has been my alter-ego for decades.

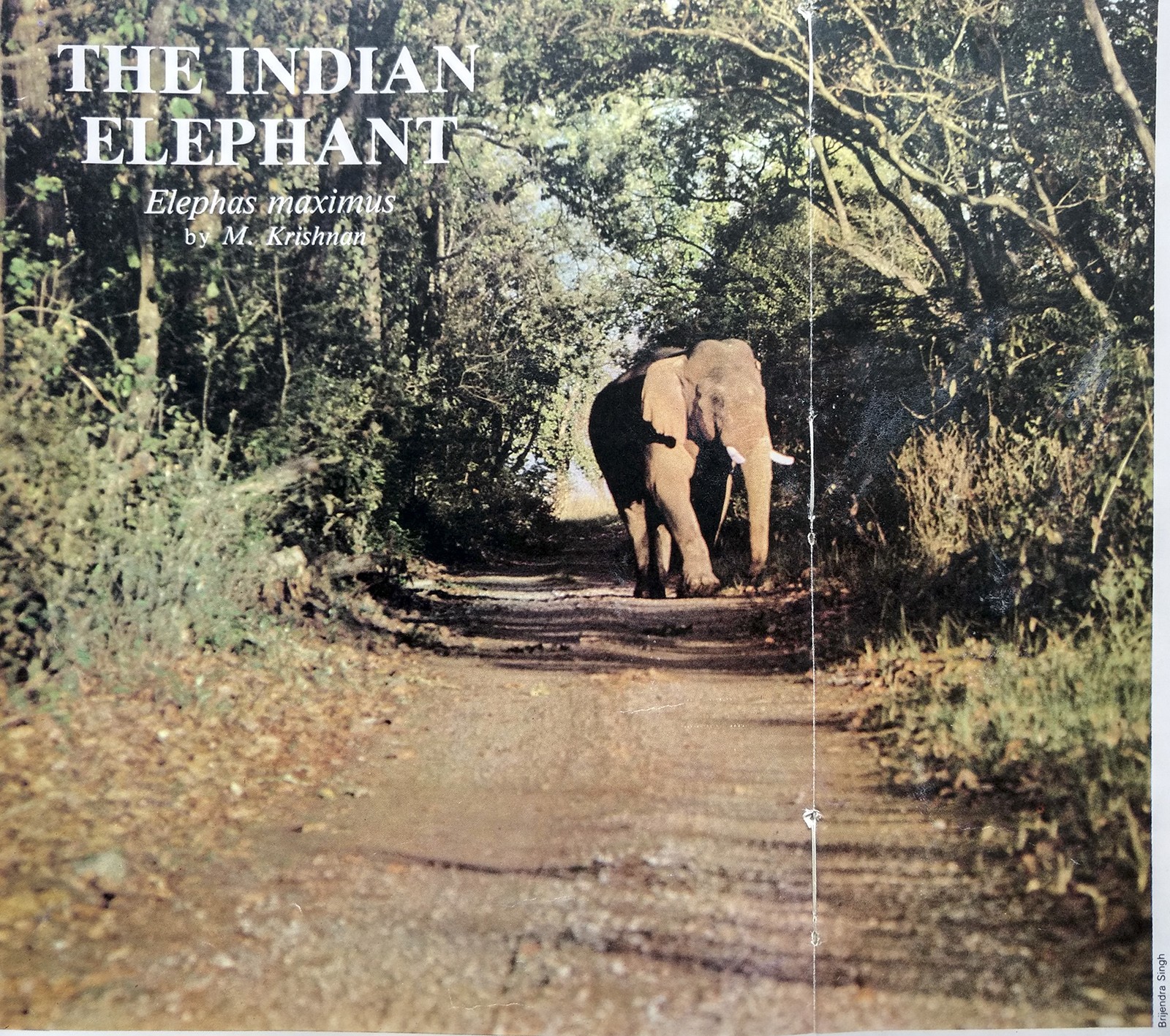

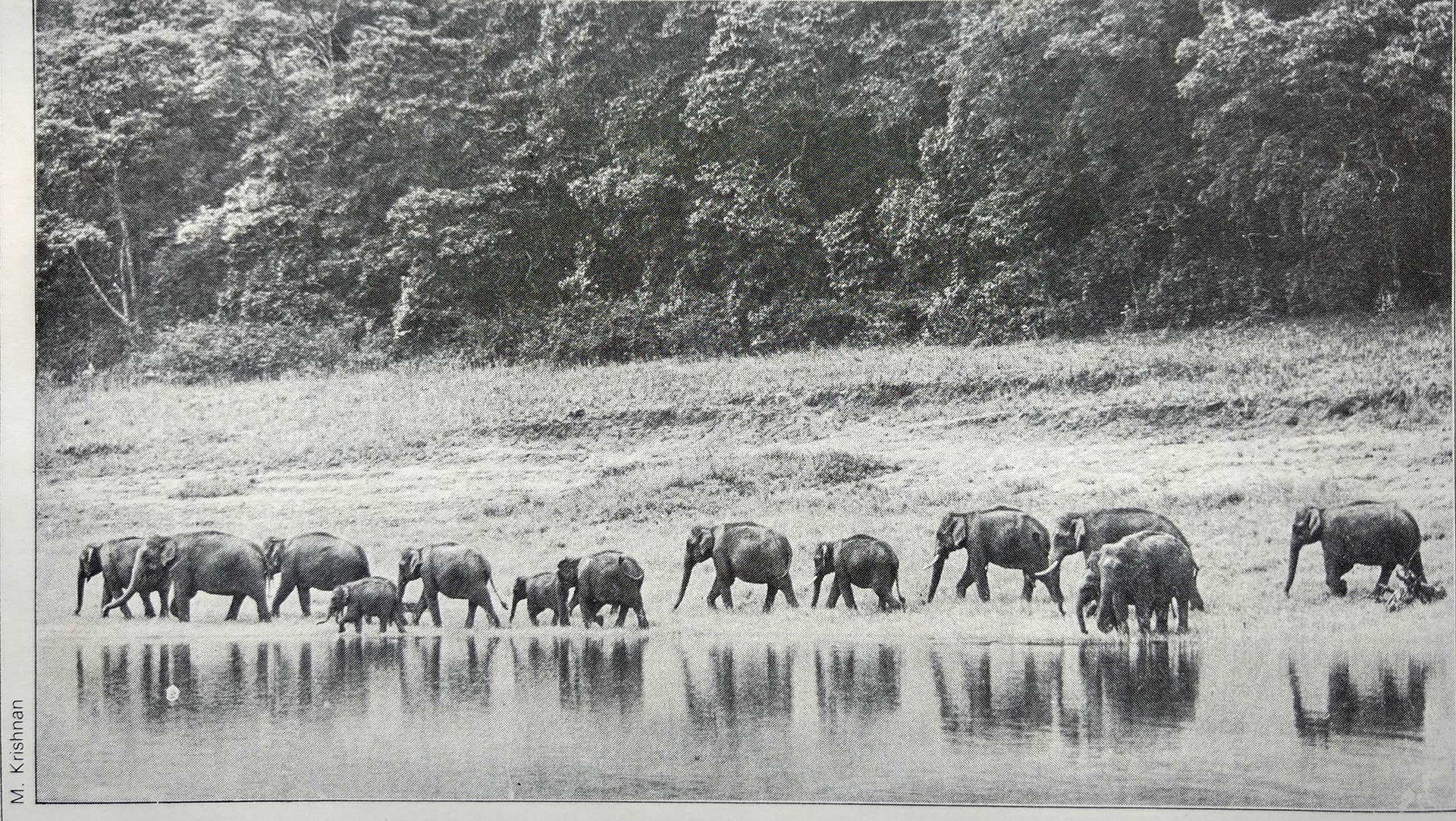

He wrote just one piece for Sanctuary in January 1982, insisting that the title should blandly read: ‘The Indian Elephant, Elephas maximus’. To date, I consider that piece one of the finest ever published in the magazine: An extract:

Given sufficient lebensraum to suit their habit of ranging far along elephant-walks, and freedom from human disturbance and predation, elephants have no problems and will create none for us, but this desirable state just does not obtain at present and seems unlikely of attainment in the future. When they find their familiar trek routes blocked by men and are confined to an inadequate tract, the disturbed animals become nervy and panic and consequently wander about aimlessly, often turning hostile to men. Further, though they have been long protected by legislation, poaching for ivory has taken a heavy toll on them and has added considerably to their sense of insecurity and their aggressive response to humanity.

Today, in the age of digital photography and social media, I wonder sometimes what M. Krishnan might have to say about the endless stream of nature writing and photography that floods through the world, most of it without fact-checking, much of it plagiarised.

I feel privileged to have known this original thinker who wrote from personal experience, checking and cross-checking versions with great diligence and an almost pathological respect for history and natural history.

M. Krishnan was a legend in his lifetime. He served for years on the Indian Board for Wildlife and the Steering Committee of Project Tiger, he wrote letters to Editors of newspapers, even when he had scant respect for them (“Yes, it is a mug’s game all right, writing letters to the Editor. Sometimes I wonder why I play it”), he wrote passionately about “ecological patriotism” and was more scathing and pungent in his attack on the ecological illiteracy of the Planning Commission than any of today’s critics are. He fought with all the power in his pen against those who introduced exotic plants such as Croton bonplandianum (water hyacinth) and Prosopis juliflora (what he called the pestilent mesquite) into India. And he had nothing good to say about those who described the Himalaya as the ‘Himalayas’. Was he opinionated? Yes. Strongly so. Was he brusque and acerbic? Yes. He found it impossible to suffer fools. But was he mean and vicious? Never.

As we remember him today, on his birth anniversary, it’s best we allow M. Krishnan to have the last word. Here is his take on ‘Ecological Patriotism’, a trait singularly missing in India’s leadership today.

At times a profound truth is embodied in a jocular saying, and the classic definition of a virgin forest as a tract where the hand of man has never set foot is such a saying. Provided they are of adequate area, all manner of wildlife tracts in our country have the potential to recoup if left strictly alone, even if now heavily depleted.