It was a little past one in the afternoon, and after what seemed like hours of relentless climbing, there was still no sign of a clearing. My T-shirt was soaked in perspiration. There were three of us, including our guide, Narayana, traversing through a kingdom of trees that stood tall and wise and so dense that the dark monsoon skies couldn’t be seen through their canopy. It was difficult to say if it was 10 in the morning or three in the afternoon. The forest floor was musty with a blanket of leaves of every conceivable shade between brown and green, punctuated by the occasional fallen tree trunk.

The sound of the gurgling streams that had ceaselessly followed our trail was now lost to an uncomfortable silence. There was no din of the cicadas, seducing whistle of the thrushes, or the distant hoot of the langurs that forms the aural tapestry of these shola forests. The malabar pit viper coiled in ambush and the stunning form of a pill bug that we admired at the head of our trail were all but a distant memory. Everything seemed so motionless and placid that we could spot even a stray drop of water bouncing off a glistening leaf. It was clear that we had entered a secret, unauthorised realm.

Narayana, our local guide, mumbled, “Even animals don’t come here.”

Mohan Polamar, my yoga guru, and I had committed ourselves to a two-day trek through the rain-drenched, leech-infested forests of the Sharavathi Valley in Karnataka’s Western Ghats, with Narayana at the helm. I had called him a week earlier to find out more about the trail. “You just get here, let’s see,” was his reply, which reeked of nonchalance and condescension. During my last trek with Narayana, I had remarked that our trail had been somewhat easy and he seemed disappointed that he hadn’t pushed me enough. I now had reason to believe that he would make this as tough as possible just to prove that the terrain was his backyard, and that we were just awkward city folk. However, the imminent mystery of walking down an unknown path prevented me from probing further.

The forests of Sharavathi weren’t completely new to me; I had done a handful of treks in the valley already — twice to the 16th century fort ruins (the erstwhile abode of Chennabhairadevi, the pepper queen) at Kanoor. On one such trek, serendipity led me to the home of a humble farmer couple who gave me shelter for the night and showered me with uncommon generosity. Electricity had not yet touched their lives and I remember listening to the whole family sing folk songs after sun down, their house lit by the warm glow of a few flickering oil-lamps. In the following years, I went on to document the couple’s intimate understanding of nature and animals; in particular the rainfall that was an inseparable and vital part of their lives. Their farmstead is still my secret retreat that I head to every few months or so.

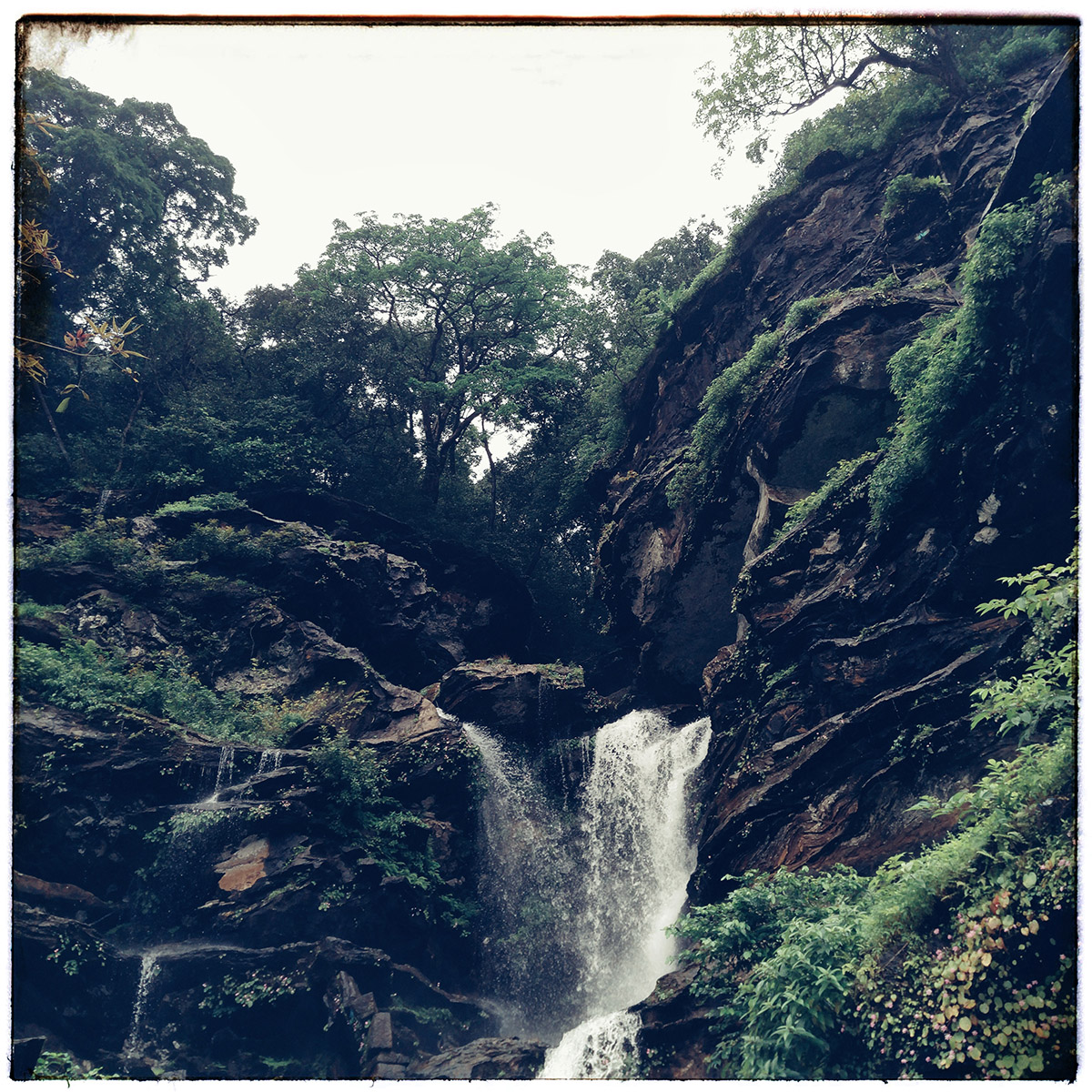

Mohan and I couldn’t have asked for a better way to begin this trek. The skies opened up as soon as we set foot on the trail, soaking us in warm monsoon showers. The trail began as a wide jeep track, meandering through patches of evergreen forests, swathes of paddy fields, and across a turbulent stream via a pretty, little concrete bridge. There was so much green everywhere that it hurt our eyes. Our first stop was the cave temple of Bheemeshwara adjacent to a waterfall that fell in tiers. The vistas of the valley’s evergreen forests from here were incredible and we couldn’t wait to hit the trail again. After a quick breakfast of sweetened avalakki (flattened rice) at the priest’s house, we entered the thickets at Narayana’s beckoning.

A good two hours or so into this terrain, I began losing steam. Mohan and I were now on all fours; tackling the slippery incline, struggling to find a foothold to hoist ourselves up one step at a time. We clumsily held on to the overhanging vines and tender tree trunks for support while watching out for stubborn whip-like vines studded with thorns. I lost my footing a few times and bruised my right arm during a slip. My recently injured left knee certainly didn’t help matters. I couldn’t tell if I was tired, hungry or thirsty. Or all three at once.

I silently cursed my decision to pick Narayana to lead us through this maze.

What if we were lost in these unforgiving jungles? A newspaper report that I had read a few years ago flashed in front of my eyes: ‘Three experienced trekkers go missing in the Charmadi Ghats.’ I began to wonder if I had left sufficient clues for people to come looking for us. To some consolation, I remembered that in my very last tweet before Mohan and I took the train to Talaguppa, I had mentioned this trip. And I recalled my encounter with a Bengaluru couple just before we took off into the jungle. They had pulled over and were contemplating a short walk in the forest — the lady was apparently petrified of leeches and had agreed to step out of the car only with an electric mosquito swatter in hand. I had pointed out to her that leeches didn’t fly.

Meanwhile, I searched for signs on Narayana’s face that would perhaps give away the fact that we were lost. There were none. He seemed as calm as before. Every 15 minutes or so, he would pause in his tracks to take a moment and carefully survey the foliage in front of him before leading us in a direction he deemed suitable. He looked at his phone only to keep track of the time. “I keep a count of the number of hills we’ve crossed in the last hour, and how many more there are to go,” he explained to me. His reassurance was enough to inject me with a sudden dose of courage and I heaved myself forward. It was half-past-three in the afternoon by the time we finally saw the light, literally. We reached the top of the mountain, a vast open space strewn with baguette-shaped rocks that were all delicately laced with a fine layer of moss. The view of the Ghats was stunning; Mohan and I each found a spot to sit on, breathe in the cool mountain air and enjoy the vistas. Narayana opened a tin of lemon-rice and fetched us water from a stream trickling along close by. I lay down on my back and as I closed my eyes, Narayana came up to me and whispered, “See, I told you we’d reach.”