Dr Raghu Chundawat does not remember his first tiger sighting, but what he does remember is how commonplace it was to sight one of these big cats. “The unfortunate thing is how quickly we forget what the past was like – for the younger generation the current situation has become the new baseline, and in the absence of documentation we fail to understand what has been lost,” writes Chundawat in his book The Rise and Fall of the Emerald Tigers: Ten Years Of Research in Panna National Park.

The Status Of Tigers In India – 2018 report by the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) states that the tiger population in India is about 2,967 – a 30 per cent increase compared to the previous report published four years earlier. This does not mean that we will be spotting tigers as commonly as Chundawat's childhood days; in fact, the new report, despite its optimistic numbers, does raise a few concerns. For example, in Chhattisgarh, tiger numbers have reduced from 46 in 2014 to a mere 19 in 2018. Books on tiger conservation which call a spade a spade and provide a wealth of information are essential in these times.

The Rise and Fall of the Emerald Tigers is based on Chundawat’s decade-long (1996-2006) research in Panna National Park. “When the tigers in Sariska went extinct, very little was learnt since no one had documented the decline or studied in detail why and how it happened. In Panna, however, we were there to witness this undesirable event and could document the inability of the system to react appropriately to the situation,” writes Chundawat. Both informative and ruminative, the book highlights the importance of a long-term study and of understanding the ecological needs of the species. Initially, focusing on study methods and establishing how scientific data should be the basis for conservation, the book then reveals the dark side of conservational practices – highlighting mismanagement and political interference in this area.

In this interview, Chundawat talks about his book, the nitty-gritty of tiger conservation, and what we can do for tigers outside protected areas.

Your PhD research was on Snow Leopards. How did you become interested in tiger research, and why did you feel the need for a long-term study on tiger populations in a protected area?

When I did work on Snow Leopards, things were a little different. The right kind of technology was not available to us. The type of data that I needed to answer some ecological questions was not easily obtainable. So, I decided that after my research on Snow Leopards, I would work with a carnivore where I could get a substantial amount of data to answer the questions I had posed for myself.

After my PhD, I started working with the Wildlife Institute of India (WII). For my first assignment, I was sent to Ranthambore National Park in '93. Tiger numbers were decreasing there in the early 90s, and right at the start of my career, I got into the complexities of tiger conservation. There was very little research done in this area, and even after 20-30 years of tiger conservation, only one study was taken up by Dr Ullas Karanth. People felt that they knew enough about tigers, but when it came to the science of conservation, we were way behind. This is why I felt that this study was needed. I did not want to go to places like Corbett or Kanha where tigers were doing well. I wanted to go to a protected area where tigers were facing problems, to understand the factors contributing to their decline. That is how I landed up at Panna National Park.

What are the major causes of reduced tiger populations within protected areas?

In the 1970s, there was a discussion about what kind of conservation planning we should undertake. The debate was around what we refer to as SLOSS, which is Single Large Or Several Small reserves. We opted for Single Large, which means we chose to create single large reserves, instead of several small reserves. Unfortunately, this decision on size was not driven by science. This was an arbitrary and subjective decision. In dry forests, for example, we now find that tigers need larger areas. In the book, I write about scale mismatch, and there is also a publication about this. We see a mismatch between what the tiger needs and what we provide. You can implement any number of conservation mechanisms within protected areas, but if the space provided is not enough, tigers will go out. When they do so, they are exposed to edge effects and human-animal conflicts. That was one of the reasons why we observed high mortality among females in Panna. If you look at carnivore populations around the world, there is always high mortality of adult males. Panna was a unique example, where we saw high mortality among females.

What are the issues with buffer habitats outside protected areas?

Buffer habitats are not well conceptualized. When a tiger uses a space, it can assess its quality but cannot perceive the threats in it. In reality, they encounter more threats in the buffer – why I get very worried when I read articles that people have spotted female tigers with cubs in these buffer zones. It means that the population which is supposed to be protected inside is also spending time outside. This puts them at a lot of risks. So, populations that use space within both the core and the buffer, live in two mortality regimes. Mortality rates can be significant in the buffer zones and small in the core regions. But this impacts the overall mortality, which is why we need to rethink the way buffer zones have been conceptualised. They need to be better protected than the core, like an egg with a thin harder shell. When the buffer becomes an attractive habitat for tigers and draws the protected population outside, this buffer can become a threat to the protected core populations.

Lack of factual information and data, you point out, has been a major issue in truly comprehending tiger populations in the country. You write that, in the early 90s, there was no data on protected areas also. How have things changed in recent times, and what can be done to get a better grasp of the present situation?

We are definitely better off now. We have a four-year census in place, and things are more systematic and reliable now. We have data on a detailed scale. People can easily verify and use this information for future studies.

Where we are still lacking is how we plan our conservation activities and in using the available information in decision-making. The protected area system works on what is called an APO, which is Annual Plan of Operations. This plan works on only a one-year vision. There are also management plans which are made for a decade. The problem is that these plans are not in sync with each other, and there is no continuity. Each year the plans are revised without necessarily taking into account what has been done, and what needs to be done. This needs to be addressed.

Data collected by the Union Environment Ministry shows that more than 1,608 humans were killed in animal conflicts that involved tigers, leopards, elephants and bears between 2013 and 2017. In your research, you have observed that tigers are aware of human presence and know how to thrive there. How can we address human-animal conflict?

Human-animal conflict has to be looked at very pragmatically. We have to understand the root of the situation. If you look closely at regions where conflicts are taking place, you will realise that these are places where animals were once present but were slowly wiped out. When animals make a reappearance due to population recovery, people are unsure about how to deal with the situation. They now have to find ways to coexist with these animals, and that is when conflict arises.

When animals are a natural part of the ecosystem throughout, there are good practices in place which minimize conflict. But when they disappear for a decade or two, these practices are replaced, and the new generation has no idea about what it means to share space with animals. When they finally see animals, they see them as a threat. People are now trying to go back to traditional ways of addressing conflict, but times have changed, and people have moved on. We have to find contemporary methods of learning to coexist with animals.

Earlier this year, it was reported that tiger deaths have reached the 100 mark again and on average eight tigers have died every month for the last four years. Half of these deaths in 2018 were outside tiger reserves. What can we do for populations that exist outside protected zones?

The future of the tiger is dependent on tiger habitats that exist outside protected areas. In these areas, tiger conservation depends on the community's goodwill. There are no incentives for them to participate in conservation. India has been very successful in one conservation model – an exclusive model, where we set aside an area and remove everybody from that area. But what we need now is an inclusive conservation model outside our protected areas. This model has to be incentivised. For example, we can look at tourism options where the primary beneficiaries are communities. When we looked at tourism revenues within non-protected tiger habitats, we found that we can generate enough money to sustain many small villages. It's time to consider various options for our tiger habitats outside protected areas.

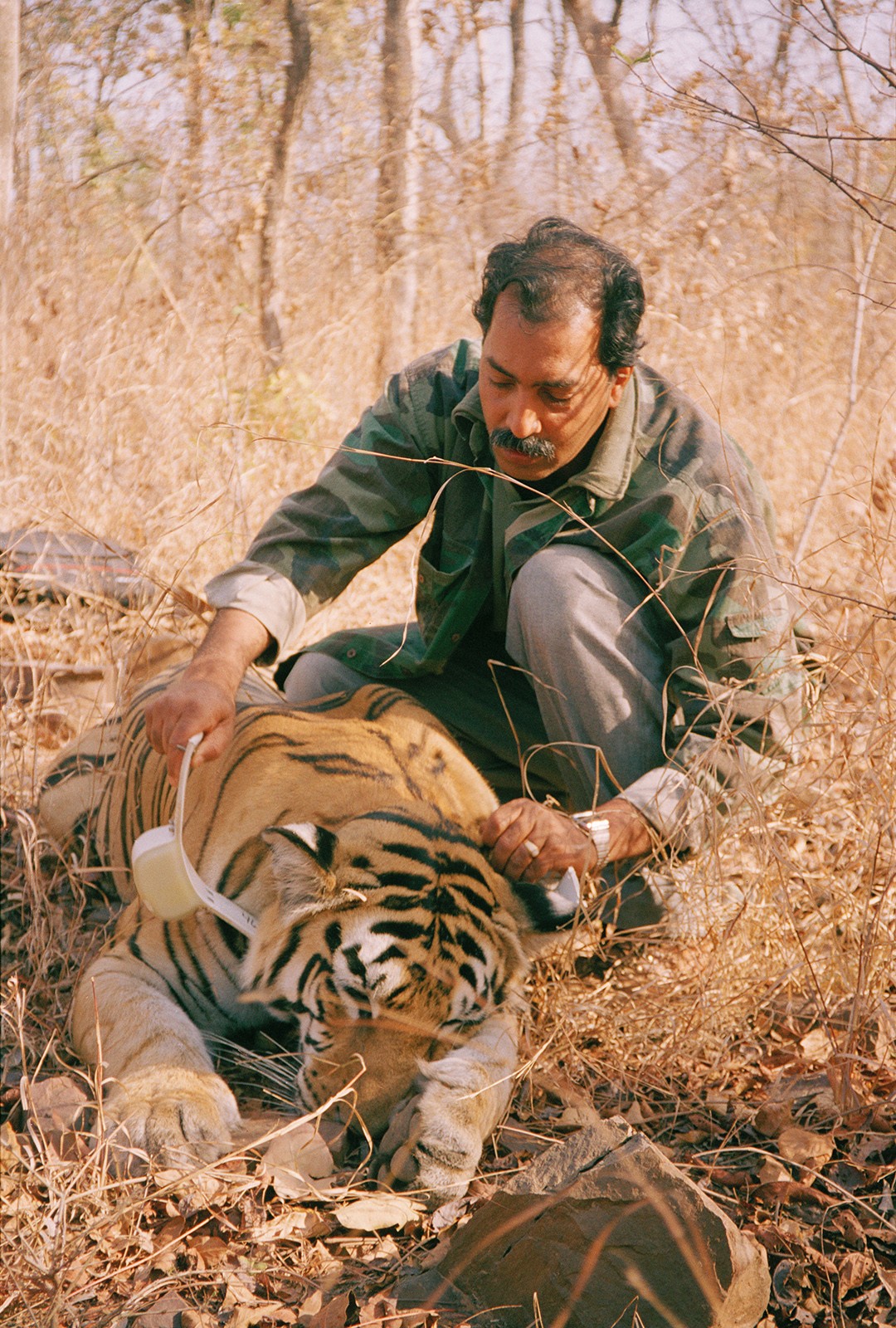

Before I end this interview, I would like to ask you about Baavan, the tigress who provided you with a wealth of information through your journey in Panna. Would you like to share the story behind her name and your experiences with Baavan?

One of our field assistants used to call this female tiger Baavan. So, we asked him why he came up with this name, and he mentioned that her eyebrows read 5 and 2. Just look at her picture, he said. That is how we began calling her Baavan. She was the first tiger we saw when we went to Panna, and she was almost the last individual we saw when the work ended. She survived the turmoil – the rise and fall of the tigers – and gave us a lot of information. She also contributed the largest number of tigers to the Panna population at the time. It was a big loss when we lost her.

'The Rise and Fall of the Emerald Tigers: Ten Years Of Research in Panna National Park' has been published by Speaking Tiger. The book can be purchased on Amazon and in various bookstores. A Kindle version is available too.