Humans have been drawn to the oceans for 50,000 years, first using rafts and reed boats and then advancing to dugout canoes and sailing vessels, and finally, mechanically propelled ships. Seventy percent of this planet’s surface is covered by water – we explore it from the North Pole to the South and across the large swathes of the Indian, Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

The oceans have always piqued our curiosity. They awe, enthral, feed and nourish us. It will suffice to say that the oceans are at the core of the life-support system of this planet. The oceans are the planet’s biggest carbon sink, they provide food to a billion people and are directly responsible for every second breath we take. In fact, for World Oceans Day this year, the United Nations theme is “Our oceans, our future” – the future of our home, Planet Earth, is indeed inextricably linked to the future of the oceans.

Today, two narratives will dominate the conversation around the oceans. One, that the world’s oceans are in a state of disrepair under the combined threats of climate change, pollution, debris and over-fishing. And two, how wild, beautiful, wonderful and magical the oceans are. Social media will carry messages calling for all stakeholders to unite, for the public to engage and for the politicians to act to save the oceans. The word ‘fight’ will figure multiple times turning the oceans into a battlefield, where individuals must enrol themselves to win against the evil destroyers of the blue lungs of this planet.

I am going to dwell upon who these evil destroyers are.

The world’s oceans are divided into two zones – Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and the High Seas. The EEZs (a zone that extends 200 nautical miles, or 370km seaward from the coast) fall under the jurisdiction of a state. In this zone, resources are governed by the state using the principle of the Public Trust Doctrine. This basically implies that the state owns the natural resources (such as fish) but must protect and maintain them for the public’s use. The areas beyond national jurisdiction are known as the High Seas, covering 50 percent of the world’s oceans. Under international law, the High Seas are recognised as the common heritage of mankind, implying that the resources are common to every single individual. Therefore even today, within both the EEZs and the High Seas, the bedrock of their exploitation must be founded on the understanding that the waters are the Commons.

Since the 1950s, there has been a thrust by economists to introduce private property rights over ocean resources, a move to take away the commons and hand them over to private players. This was based on the premise that the commons were doomed if left to be accessed by all – a precursor to the idea of the “tragedy of the commons”. Therefore, it was thought necessary to create a system that charged a fee for accessing these resources. This gave rise to the modern-day model of fisheries governance.

However, the model of handing over the reins of public property, whether in the EEZs or the High Seas, to a private entity, is invariably a destructive one. Instead of being founded on the principles of equal distribution of resources, this model focuses on maximum rent generation and economic efficiency. Closer to shore, it displaces small-scale fisher peoples by ‘invisiblising’ their traditional access regimes, thus denying them the basic universal respect for human rights. Small-scale fisher people provide for nearly 60 percent of the fish for human consumption, and so recognising and supporting their knowledge, culture, traditions and practices should ideally form the basis of fisheries governance. Away from shore, this private property model has created a cost-driven low-road business model which favours the use of sub-standard ships, illegal fishing, seafood fraud and the use of indentured forced labour. In addition, industrial distant-water fishing is sustained on government subsidies i.e. without cheap fuel, the offsetting of construction costs and favourable (destructive) operating policies, these vessels would be out of business.

When public property is handed over to private players, the government is engaging in, what is described by the World Forum for Fisher Peoples as ocean grabbing. “Ocean grabbing means the capturing of control by powerful economic actors of crucial decision-making around fisheries, including the power to decide how and for what purposes marine resources are used, conserved and managed now and in the future. As a result, these powerful actors, whose main concern is making profit, are steadily gaining control of both the fisheries’ resources and the benefits of their use.”

In 2012, I was walking down a street in Nuku'alofa, the capital city of Tonga, a Polynesian kingdom of around 170 South Pacific Islands. I have always been fascinated by the history of this particular ocean; in fact, maritime explorations in the Pacific Ocean played an important role in shaping the world as we know it today. What a glorious time in human civilisation it must have been when the islanders boarded their wooden wakas, and relying solely on the wind and the stars, voyaged east to successfully find and settle in newly discovered islands.

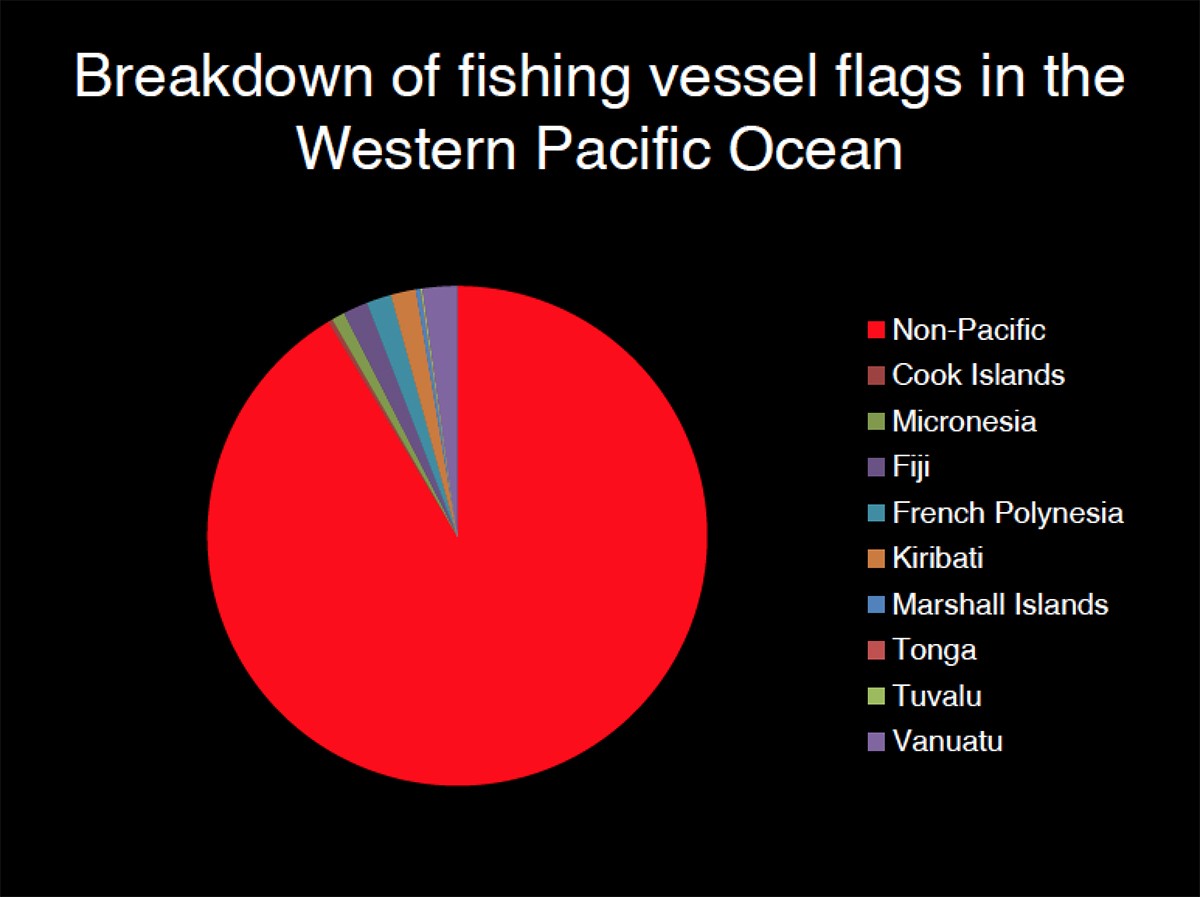

For the last few decades, a different kind of exploration has been underway in the Pacific Ocean. Steel-hulled fishing vessels, guided by electronic fish-finders, chase the ocean currents in search of tuna. Measured in economic terms, the value of this ocean is approximately between USD 4-5 billion dollars – it supplies over 60 percent of the world’s tuna. The Western and Central Pacific Fishing Commission’s (WCPFC) record of fishing vessels shows a total of 4,652 fishing vessels, of which only one is registered in Tonga.

As I walked, discarded instant noodle packets rolled by me in the gentle balmy breeze of the Pacific Islands. With the resources sold to private players, the islanders are no longer ocean bound; the seafood in their diet has been replaced by instant noodles and ground beef. The ocean had always been the Polynesians’ greatest resource, but today “te mana o te moana” or the “spirit of the sea” of the Pacific Islands has been altered forever.

70 years ago, the economic historian Karl Polanyi wrote that “Enclosures have been appropriately called a revolution of the rich against the poor”. He meant it in the context of land owners in medieval Europe who had displaced peasants and taken control of village commons. The creation of enclosures, by claiming private ownership over a shared land, is essentially what has been replicated in today’s fisheries governance. The introduction of trawlers in the 1970s was the first move by the Indian government to create enclosures. Coastal waters which had been accessed by small-scale fisher people for generations were sold to private fishing companies. The newly drafted National Policy on Marine Fisheries is a similar, larger scale move where the Indian commons, the EEZ, is being auctioned to private players. Every time we support a policy that allows for the privatisation of the commons, that displaces a community or takes away from the basic human rights of an individual, it is us who become the evil destroyers of the oceans.

Have you read the other stories from our World Oceans Day series?

A Lens On The Ocean: An underwater photographer shares his top tips on shooting in the deep blue. Dive in with Anup J Kattukaran.

Life In The Undercoral: Looking for the small stuff on coral reefs. By Shreya Yadav