“You should read about the way the British went to discover this bat in 1913…” said my companion Rahul Khanolkar. “On a bullock-cart!” he continued as he deftly avoided a small ditch on the boulder-strewn road.

Twenty-four hours ago, I was lamenting over a failed permit application. Eighteen hours ago, I was explaining my work to the Deputy RFOs and forest guards. “This is the first time we’re reading an application to work on bats!” they said. After further discussion and negotiations, I was excited to be on a bike with Rahul, retracing the path that the British took exactly a century ago in search of this fascinating bat.

The Wroughton’s Free-tailed Bat (Otomops wroughtonii) is a handsome bat dressed in judicial colours: a black coat with a white neck-tie. Discovered in 1913, for over 90 years no sightings of this bat were reported from any cave other than the Barapede caves in the Belgaum district of Karnataka. In 2001, bat biologists Paul Bates and Adora Thabah mist-netted a foraging individual near the Siju caves in Meghalaya. Subsequently, another individual was netted further eastwards in Cambodia. The erstwhile critically endangered species then got elevated (or demoted?) to a data-deficient status under the IUCN Red List. Since then, however, repeated efforts to find its populations in Northeast India and Southeast Asia have proved futile. It was only two years ago that Swiss and Indian scientists, in collaboration with recreational cavers, were successful in discovering a population of bats in the Siju-Balpakhram landscape of Meghalaya.

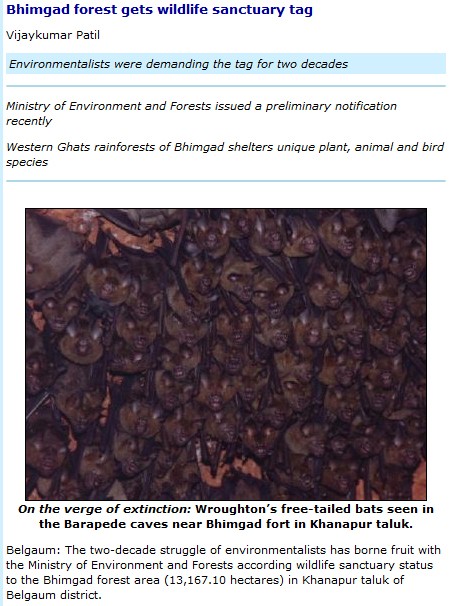

On that expedition four years ago, we reached the Barapede caves at noon. Our objective until dusk was to make preliminary observations of the Wroughton’s bats, such as colony strength, group size, roosting behaviour, the diversity and abundance of coexisting species, and to see how they responded to human presence. This would be followed by a brief reconnaissance of the surrounding landscape. We observed that the Wroughton’s bats roost within rugged indentations on the roof of the cave, in clumps ranging from 7-40 individuals.

In an allied African species, the Large-eared Free-tailed Bats (Otomops martiensseni), these groups are known to be colonies of 1-2 males, with their harem of females and dependent young from the previous litter. Though this seemed a plausible social structure for the Wroughton’s bats too, it required validation. We identified seven such groups within the cave with an estimated strength of up to 200 individuals. Two other species – the Lesser False Vampire (Megaderma spasma) and Rufous Horseshoe Bats (Rhinolophus rouxii) – were also found roosting in the cave.

Early records mention that the Wroughton’s bats immediately take off when disturbed. However, we saw that these bats rarely fly. On almost all occasions when the bats were shone upon with a flashlight, they started crawling over each other.

After noting down our observations, Rahul and I came out of the cave to check the surrounding habitat. The caves are at an elevation of 800m atop a lateritic plateau. Lateritic plateaus are characteristic of high rainfall areas in the northern Western Ghats where dense hill forests terminate in flat grasslands, interspersed with bare lateritic rocks at higher elevations. As the sun began to sink beyond the hills of Goa, Rahul gave me a thorough overview of the history and geography of the landscape. His familiarity with these hills and his love for the wilderness was evident in the way he spoke of them. On one side of the cave lies Talewadi village, which was the proposed site for iron ore mining. On the other side are the sprawling hills of Mollem National Park and Mhadei Wildlife Sanctuary, dissected by the slithering Mhadei River.

Much of the last two decades was a period of lows for this forest landscape, until then not known by any official designation, but called ‘Bhimgad’ after an old heritage fort of Shivaji situated in the Mhadei basin. Illegal tree-felling and conversion of forest land for agriculture was rampant. An even bigger threat loomed large when mining operations commenced in this iron-rich belt, with one of the epicentres in Talewadi.

Amidst all these dark clouds, the only ray of hope – a petition filed in 2003 by a local environmentalist, Durgesh Kasbekar, to declare Bhimgad a wildlife sanctuary – was gathering dust on judicial shelves. To make matters worse, here, unlike in other parts of the country, tigers existed on ground but not on paper. The state government remained adamant that only nomadic tigers were sporadically seen in this part of Karnataka. In spite of Bhimgad’s rich biodiversity, the apparent lack of the supreme umbrella species prevented its protection.

It was time to pass the baton to a new flagship species – the Wroughton’s bat. Like the lions of Gir, this bat was then known to occur in only one cave in the whole world, and it was here! Suddenly, all news about Bhimgad began to include a special mention of the bat’s rare existence in these forests. For the first time in the Indian conservation movement, a bat had been given centre stage.

It took a while: a unification among national and international NGOs fighting for the cause, and even a change in governance. In 2009, the movement to protect Bhimgad started gaining momentum. Finally, in 2011, the then Deputy Conservator of Forests Girish Hosur announced that a 200 sq.km area had been declared as Bhimgad Wildlife Sanctuary (WLS). This protected area is now contiguous with the Mhadei WLS, Bhagwan-Mahaveer WLS, Mollem National Park (NP) and Netravali WLS in Goa, Radhanagri WLS in Maharashtra and Anshi-Dandeli Tiger Reserve in Karnataka. Evidently, it is a vital tiger corridor and also a critical river basin. Every environmentalist from north Karnataka and Goa would tell you how significant a battle had just been won. In this game, a bat had played the trump card.

“But we still don’t know anything beyond what we knew in 1913,” said Rahul as we were riding back to Belgaum. He was right. In spite of being discovered a century ago, there is precious little that we know about the Wroughton’s bat. What do the bats eat? How is their society structured? Where do the young ones disperse during and after breeding? Is their population increasing or declining? These and several other questions await answers, and until we get them, we may not be able to devise proactive conservation measures. But for now, perhaps we can sit back and cherish a hundred years of acquaintance with the bat that saved a forest.

Note: This article was originally written in May 2013. The events described in the article happened during the later days of my schooling, which were also the earliest days of my interest in wildlife. The chronicles of the conservation story of Bhimgad are likely to have some gaps and I’ll be happy to have those pointed out.

This story first appeared on Rohit Chakravarty’s blog about bats, Blah ka Nas.