In 2011, the Census of Marine Life announced that the estimated number of species on our planet is about 8.7 million. Considered one of the most accurate estimations in recent times, this analysis also predicted that within the 8.7 million, animal species accounted for about 7.77 million.

Luxuriating in an urban setup, it is hard for us to imagine that we share this planet with so many other species. For the most part, we are able to get through our day without having to make allowances for its other residents. Even when we account for our animal encounters, they are limited and often by choice. But this is not the case everywhere, and a new book shows us exactly that. In places where lives and livelihoods depend on human-animal interactions, animals come to play a vital role in everyday life.

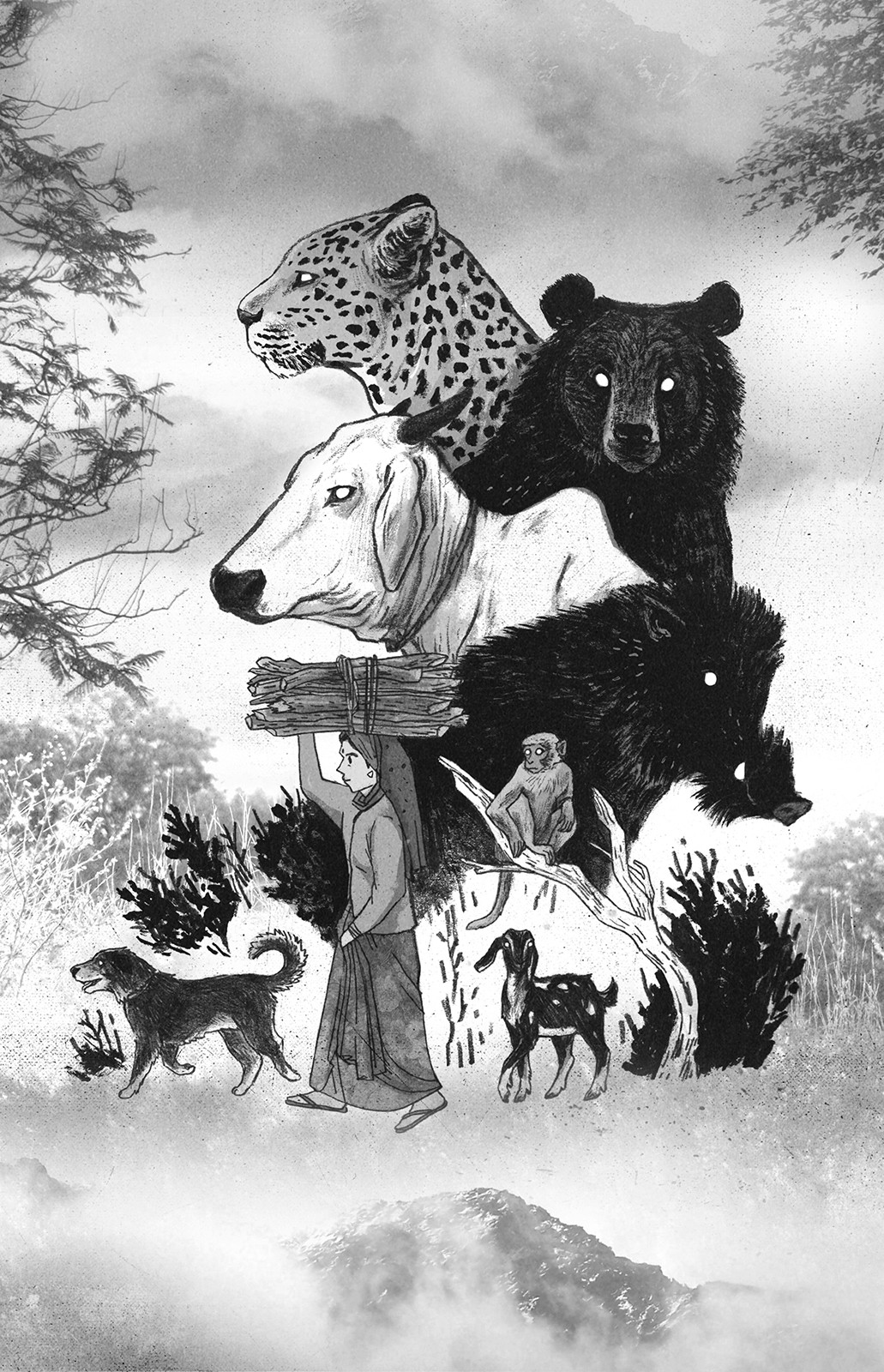

Animal Intimacies: Beastly Love in the Himalayas, written by anthropologist Dr Radhika Govindrajan, explores the many visible and invisible threads that connect human and animal lives in the Kumaon villages of the Uttarakhand region. Against a rural backdrop, Govindrajan looks at what it means to share space with other species that are at times a source of livelihood, other times a source of despair and some times a projection of the ongoing political and social problems. Observing ways in which interspecies relatedness manifests itself, Govindrajan provides context for various issues like ritual sacrifice, cow protection, human-animal conflict, and rural-urban migration – showing us how nuanced these issues and these relations often are.

Radhika Govindrajan is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Washington. Her research interests include multispecies ethnography and political, religious and environmental anthropology. For her book Animal Intimacies, she won The Edward Cameron Dimock, Jr. Prize in the Indian Humanities. Over a phone call, Govindrajan talked about her book, experiencing these relations up close, and how effective conservation measures require an understanding of the landscape, people and animals.

How did you go about researching human-animal interactions? Where does your interest in this area of research stem from?

I was trained as a historian, and I have always been interested in understanding the history of conservation in India. During my Master's degree, I did some research on early wildlife conservation in the United Provinces of British India, present-day states of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand. When I travelled in that region for research, I found that a lot of the questions on how conservation came to be defined had a contemporary resonance to them. As I started training in anthropology, I became more widely interested in the question – how do people live alongside wild animals? I realized that it couldn't really be separated from how they lived alongside other kinds of animals (domestic). The categories of wild and domestic were so fluid and shifting that it didn't make sense to isolate one from the other. I became more and more interested in how these categories had come to be historically and how they broke down in the process of everyday life.

You conducted your research for Animal Intimacies in villages along the forest edges in the Kumaon region. Why did you choose this region for your research?

As I said, my historical research had been in that region and I was looking at the writings of people like Jim Corbett, Frederick Walter Champion – a wildlife photographer who was very active in the Himalayan provinces in the 1920s and 30s, and pioneering forester EP Stebbing, who also worked in that region. So it made sense to continue the project there. Added to that, the state is a biodiversity hotspot and a favoured spot for conservation.

Also, these rural areas are undergoing such a dramatic transformation that it became an interesting place to think about what rural life looks like. On one hand, there is large scale agrarian abandonment in this area, and people have stopped farming for multiple reasons. But on the other hand, it is also a preferred region for people to buy land and second homes. These are interesting conditions, in which people are thinking about the value of agrarian work and what it means to live the "modern life". For these reasons, the forest edges of Kumaon seemed like the right place to locate my research.

Very early in the book, you mention that these are not "idyllic villages", but represent a fluid and complicated world. There is the ongoing issue of migration to cities in search of better prospects. This migration is often discussed from an agricultural context, but what are its implications when we talk about the human-animal interdependencies?

The rapid departure of young people from these villages was creating unexpected changes in the region’s landscape. Abandonment of agrarian land paved the way for new kinds of microhabitats that became home to tall grasses, secondary growth shrubs and trees. Increasingly, wild animals like leopards and boars began to move into these spaces, confounding any easy distinction between a field and a forest. The boundaries were blurred.

The other thing that migration has done for such a long time, and continues to do is produce a shortage of agrarian labour. This creates a domino effect where people are leaving because agriculture is untenable and their actions make agriculture even more untenable. The impact of climate change is also a contributing factor here. I worked in a largely fruit producing area, and over the last few years, people are unable to cultivate these fruits due to changing monsoonal patterns and increasing temperatures.

Also, when agriculture becomes more difficult, people turn to livestock keeping, which meant the number of domestic animals also increased in these regions. People were keeping more goats and cows and looking at dairy and meat as alternate sources, even though these practices are not that easy. In the face of migration and climate change, these broader social and economic shifts were visible.

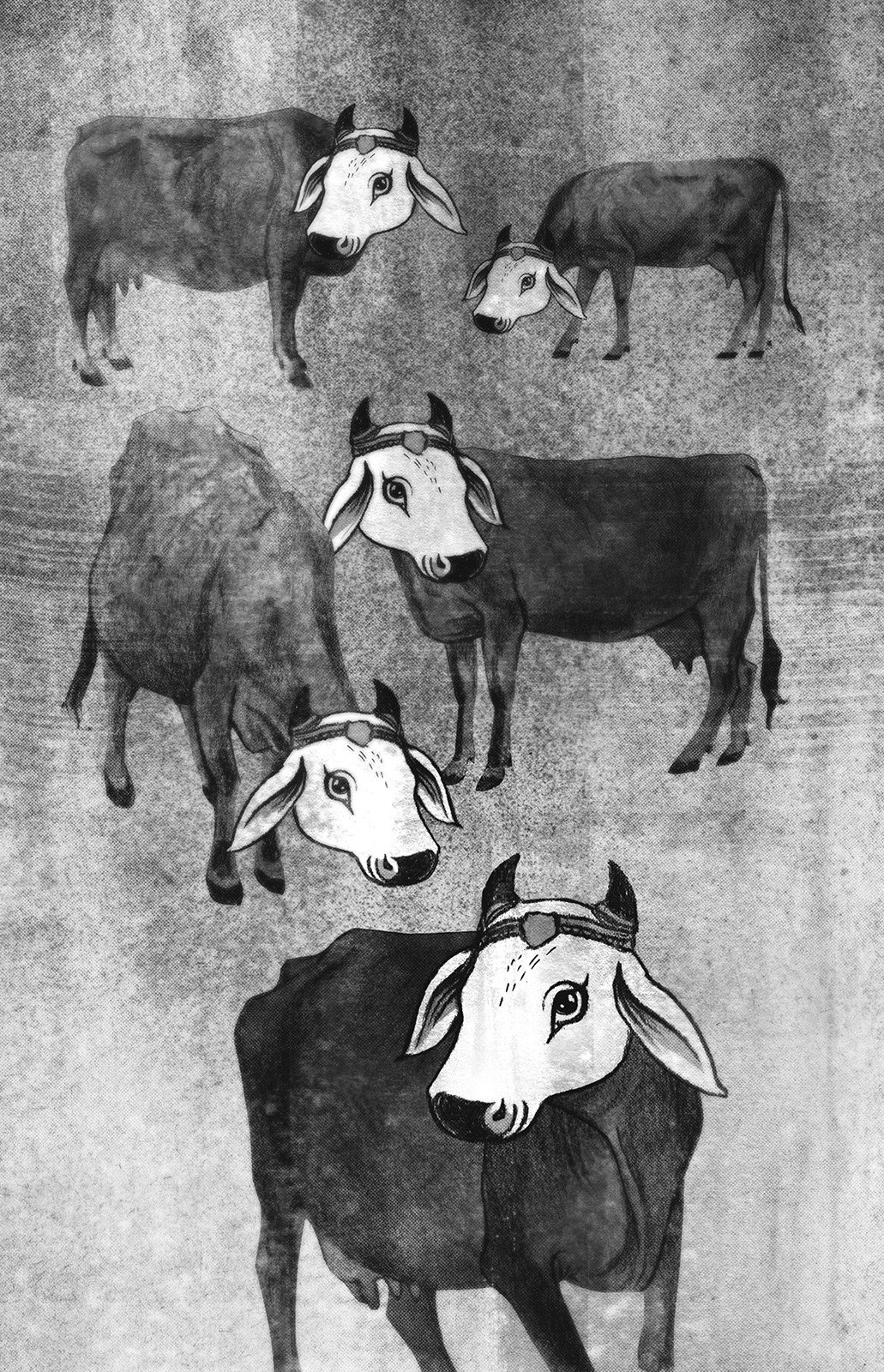

There is an undertone of native species protection that we witness in the way people refer to the local species as pahari (native) and the rest as non-pahari (outsiders) – even when it comes to their own livestock. What is your take on these distinctions?

It is important to understand here that even though people were making these distinctions between native and outsider species, they were not hard and fast. For example, as I mentioned in the book, people say that Jersey cows could become of that region, after a few generations. While there was a certain kind of native disposition, it did not turn into xenophobia, so to speak. People were open to working with animals that were brought in from elsewhere. It just complicated their relationships with these animals, and they had to work them out through daily interactions. Even though there is this a strong sense of pahari identity, how that manifests does shift.

The other thing is people are aware of the importance of these, so called, outsider species – plants and animals. There is an interest in bringing in apples from Himachal Pradesh to make cultivation more lucrative. There is an embrace of Jersey cows that provide rural households with money from dairy and meat. People realize that plants and animals walk between places, and this isn't something they want to shut down. This has created certain conundrums which they navigate in their own ways.

In the chapter on wild pigs, you write about the frustration that villagers face as their crops get destroyed by these animals on a regular basis. Conservation policies, you point here, do not take into account the difficulties that cultivators face. In your opinion, how can policies strike a balance between species protection and prevention of crop damage?

What we see increasingly today is that certain species are thriving in human-dominated landscapes. This is a point that wildlife biologists have been making for a while now, but it has not really caught on in conservation circles. Wildlife biologists like Vidya Athreya argue this fact, in the case of leopards. We certainly see this with species like the wild boar, which feed on people's crops. Conservationists need to address the fact that animals move in and out of human spaces. It is not a simple story of humans destroying wildlife habitats, but one of the animals moving into human-dominated habitats, making it their own. I write about this in the chapter on wild pigs and towards the end, when I talk about the leopards. Even though there were leopard attacks, people understood them as part and parcel of the experience that comes with living alongside these animals. But with wild boars, the response was entirely different, and people were unhappy with their activities.

What this goes to show is that conservation has to be rooted in more localized practices. It needs to be more flexible, taking into account the individual species involved. We also have to question this fortress model of conservation that does loom large in India. Conservation comes with its own stakes and its own politics, and we have to recognise those instead of viewing it as an apolitical endeavour driven by love of nature.

What message would you like to convey to people who are far removed from such everyday animal interactions?

Something that really needs to change is this rendering of people who live alongside animals as being incapable of appreciating nature or of actually living with animals and establishing a relationship with them. These relationships exist, and they are messy and complicated. We have to be attentive to the nuances and textures of these everyday relationships. Also, we have to understand that there are no simple answers to the questions of what ethics and justice look like. The people who do live alongside animals are trying to work these questions out in their own small ways. What we need to do is find a way of valuing that kind of daily work.

It's hard to come up with one message, but what I realized through my research is that the only way to work out these broader ethical, conservationist and political questions is by staying and dwelling in the complexities of these relationships. An understanding of the landscape, people and animals, is, therefore, essential. For me, that is the thing to take away from this experience.

Images courtesy of Penguin Random House. Illustrations by Prabha Mallya.